Capitol Journal: Vaccine legislation properly puts public health above personal beliefs

- Share via

Ask most rational people what their No. 1 priority is and, I suspect, they would answer good health.

Love, friends, money, freedom, a good education, a productive life — they’re all right up there. But none outranks health.

So it’s pathetic that more legislators aren’t fully embracing a bill that essentially would tell parents: Vaccinate your kids against infectious diseases or they won’t be allowed in school where they could jeopardize the health of other children.

The bill’s only exception: Parents whose children have a medical condition — a weak immune system caused by leukemia, for example — that might not tolerate a vaccination. They can get a doctor’s note and be excused from the shots.

You parents who won’t permit vaccinations because of a personal belief, well, you’re free to practice that belief any way you’d like — as long as it doesn’t threaten other people’s kids.

Americans do have freedom of religion — but not the freedom to jeopardize the health of other Americans.

That’s the way it should be, anyway, and how a bill struggling through the Legislature would make it in California.

The measure, SB 277, finally cleared the Senate Education Committee on Wednesday on its second try. A week earlier, it stalled when committee members worried that it would deny unvaccinated children their education rights.

The bill would eliminate “personal belief” as a legal excuse for refusing to have children vaccinated before they enter school.

Under compromise amendments — which semi-satisfied legislators, but not the bill’s opponents — unvaccinated children would have broader options for education besides single-family home-schooling. They could join other families in creating a private home-school. Or they could use existing independent study programs run by local school districts.

The bill still must clear two more committees. If passed by the Senate, it would face a tough fight in the Assembly.

Gov. Jerry Brown is sending signals he’d be inclined to sign the bill.

“The governor believes that vaccinations are profoundly important and a major public health benefit,” says Brown’s chief spokesman, Evan Westrup. “And any bill that reaches his desk will be closely considered.”

The bill is jointly authored by Sens. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), a pediatrician, and Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica), a former school board president whose father had polio as a child.

Besides polio, kids are required, before entering school or child care, to be immunized for such communicable diseases as diphtheria, measles, mumps, whooping cough, chickenpox and hepatitis B.

But California has the “personal belief” exemption that increasingly has resulted in parents refusing to inoculate their children. Besides a religious belief, many are scared that vaccinations can cause other ailments.

Many mistakenly believe, for example, that a measles shot can lead to autism — a discredited theory promoted in 1998 by a lying researcher. His study later was retracted by the journal that published it. And many studies since have shown there is no link between vaccinations and autism.

Statewide, the immunization rate for kindergartners is roughly 90%, according to the state public health department. But in some mountain counties — Humboldt, Mariposa, Nevada, Tuolumne — it’s down into the 70s. And in some pockets, it’s in the 50s, a place ripe for disease spreading. The rate has been gradually declining in recent years.

Experts say that low vaccination rates fueled the measles outbreak that started at Disneyland in December, sickening 157 people and inspiring the legislation.

“Each year we’re adding to the number of unvaccinated,” Pan says. “If it gets low enough, that’s when disease is able to spread. Because so many people haven’t experienced these diseases, they don’t know how serious they are.”

Relatively few people today remember the frightening polio epidemics before the Salk vaccine was introduced in 1955. There hasn’t been a case of paralytic polio in the United States since 1997. Credit polio shots. But the disease continues to ravage people in 10 countries. So it still can be transmitted to unvaccinated Americans by foreigners.

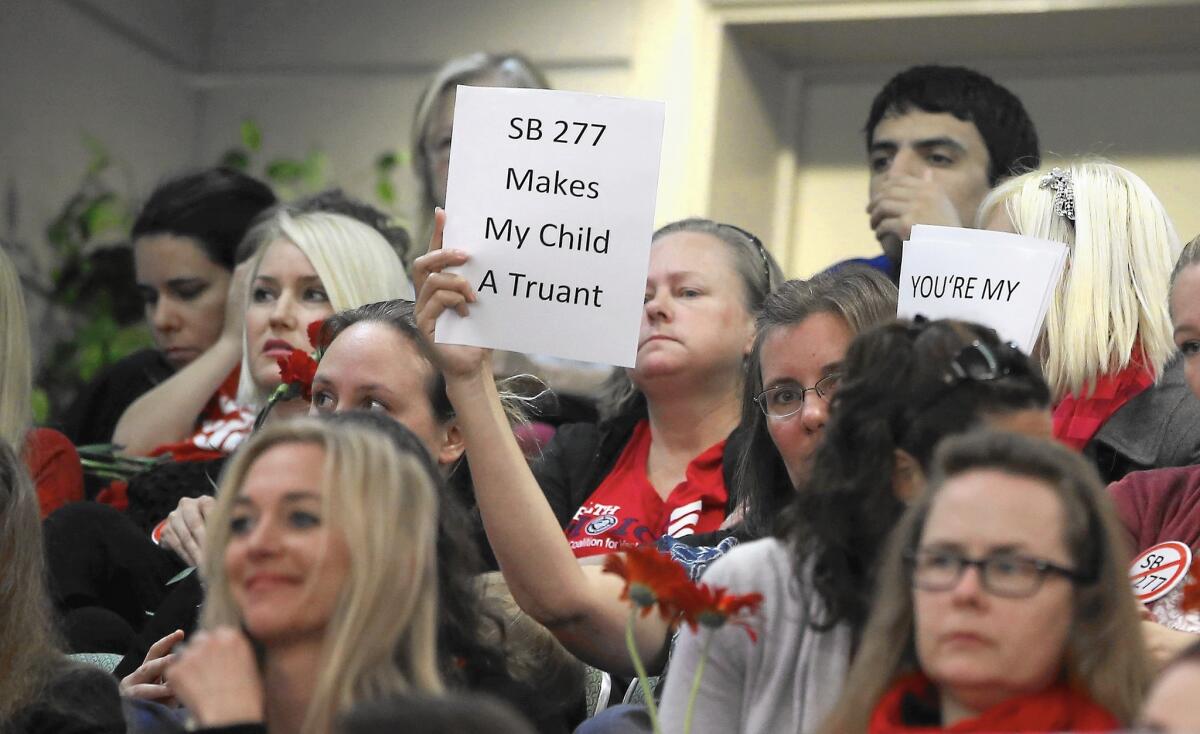

During the Senate Education Committee’s fiery hearing last week — attended by hundreds of angry parents — a polio survivor told about being stricken at age 7. She urged passage of the bill, speaking in a voice apparently weakened by respiratory problems.

Later, she was mocked on Facebook by two opponents of the bill. “Lisa” referred to “the hysterical polio survivor” and added: “Poor woman needs emotional therapy.” “Annika” responded: “Polio was really DDT poisoning.”

Polio has been around thousands of years; DDT about 80.

“The level of vitriol [over the bill] is the highest of any I’ve experienced,” Pan told me. He and Allen both have received death threats from opponents who claim they have a parental right to not vaccinate their kids.

OK. But we also should have a right to keep them away from other school kids.

In 1951, before there was a vaccine, more than 10,000 Americans were afflicted with paralytic polio. I was one. My strong single mom guided me through the ordeal. She was a saint.

But if there had been a polio vaccine that she had prevented me from receiving, I never would have forgiven her.

Parents who won’t allow their children to be vaccinated are — let’s put it politely — misguided. That’s their problem — and their kids’.

The Legislature should gather enough courage to make sure it’s not also everyone else’s problem.

Twitter: @LATimesSkelton

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.