Gay marriage order puts spotlight again on the ‘Ayatollah of Alabama’

- Share via

Reporting from ATLANTA — When Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore issued his latest controversial order on gay marriage, urging probate judges to stop issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, many considered it a brazen, last-ditch act of defiance against the U.S. Supreme Court.

The long-contentious chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court didn’t see it that way at all. Merely a humdrum matter of procedure, he explained. “At this point, I am not defying the United States Supreme Court,” the staunch 68-year-old Baptist and Republican said.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

When it comes to Moore -- dubbed the “Ayatollah of Alabama” by a civil rights group and chided by the daughter of the late George Wallace as being more dangerous than the combative former governor -- little is ever just humdrum procedure.

Few have put their stamp as firmly on modern-day Alabama in such polarizing fashion as Moore. Two decades ago, he became known as the “Ten Commandments” judge after he put up a wooden plaque quoting the biblical commandments in his Etowah County courtroom.

When he was elected the state’s chief justice in 2000, Moore installed a 2 1/2-ton granite monument to the Ten Commandments in the rotunda of Alabama’s judicial building.

“In order to establish justice,” he told a crowd at its unveiling, “we must invoke ‘the favor and guidance of Almighty God.’”

Three years later he was removed from office when he defied a federal order to remove the monument. But then in 2012, he made a comeback, again winning election as Alabama’s chief justice.

Now he’s elbowed his way back into the news with his legal reasoning that the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in July on same-sex marriage only has standing in four states – Michigan, Kentucky, Ohio and Tennessee.

It did not, he argued, automatically strike down the Alabama Supreme Court’s previous order that judges not issue marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples.

“It couldn’t serve as precedent because we ruled first,” Moore said of the Supreme Court ruling, Obergefell vs. Hodges.

Many legal analysts dismiss his latest bid to block gay marriage as nonsense.

“The Supreme Court decision has authoritative precedent that binds all state officials,” said Ronald Krotoszynski, a law professor at the University of Alabama. “This is little different than a Southern governor ordering school officials to refuse to segregate schools.”

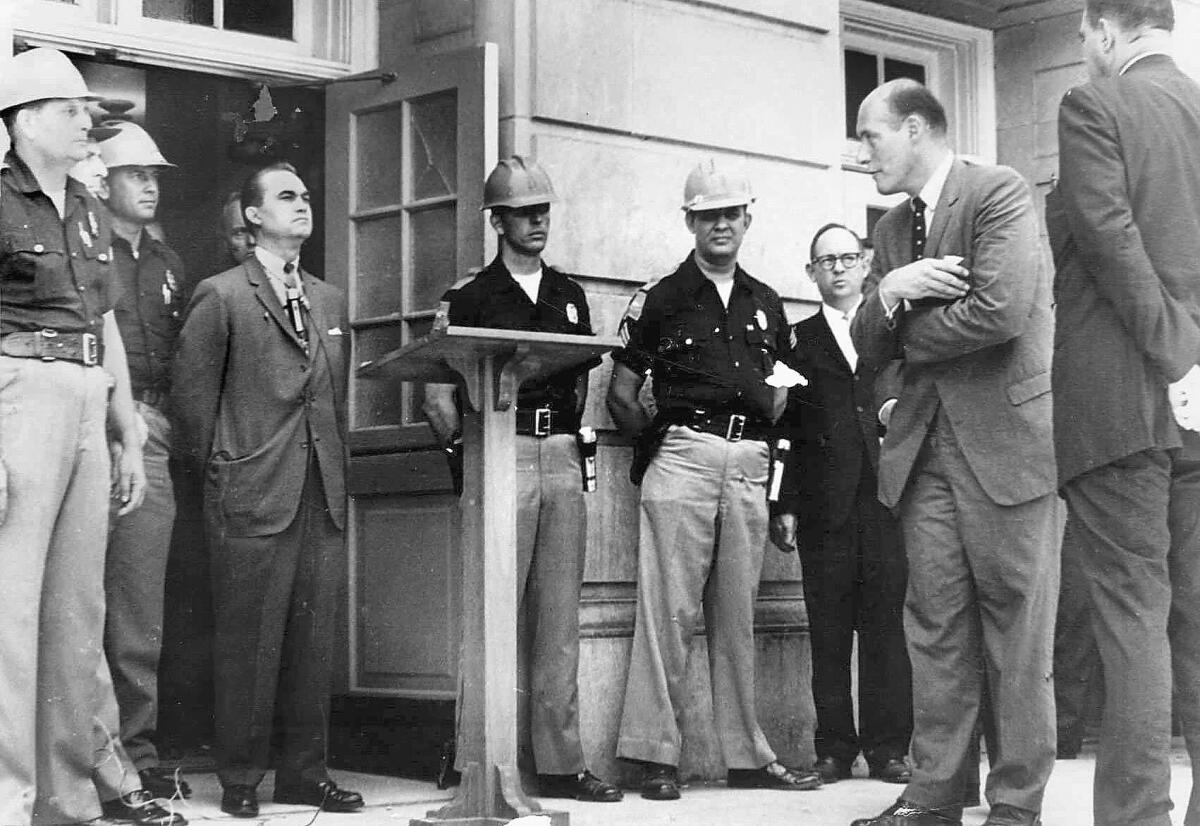

Peggy Wallace Kennedy said Moore had actually strayed further afield than her father, who famously stood in front of the University of Alabama in 1963 to defy national efforts to desegregate.

In 1963, Alabama Gov. George Wallace, wearing suit at left, tried to block the admission of two black students at the University of Alabama.

“George Wallace was able, by virtue of his office, to take political advantage by publicly promoting a theology of discrimination, but Roy Moore cannot,” Peggy Wallace Kennedy wrote about her father in an opinion piece for Al.com. “George Wallace was not confined by a code of ethics that restricted his right to rabble rouse, but Roy Moore is.”

A former boxer and professional kickboxer who once worked as a cattle rancher in the Australian outback, Moore is an eccentric chief justice, even by Southern standards. Born in a poor, rural corner of northeast Alabama -- his father a jackhammer operator, his mother a homemaker -- the values of religion were instilled early on.

After years of prayer, he was admitted to West Point, where he found his Southern accent and lack of education made him a target of intimidation. He took to the boxing ring to level the playing field.

As a military commander in Vietnam, he was dubbed “Captain America” for his attempts to instill discipline and stop illegal drug use among his soldiers. Eventually, he became so unpopular he installed sandbags under his bed and in the walls of his quarters to protect him from underlings who might try to kill him in his sleep.

Long-standing legal and political observers say Moore is no political opportunist, but a true believer who thinks he is doing God’s work. “To quote the Blues Brothers, he’s on a mission from God,” Krotoszynski said.

“He is a religious zealot,” said Richard Cohen, president of the Southern Poverty Law Center, which has filed an ethics complaint against Moore for his efforts to enforce Alabama’s same-sex marriage ban. “He believes he is a law unto himself, and he has an independent oath to interpret the Constitution.”

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Moore declined to express his opinions on gay marriage, saying he would restrict his comments to his administrative order.

He was not always been so reticent.

In 2002, he delivered a widely criticized opinion in a child custody battle between a father of three children and his former wife, a lesbian. Homosexuality, Moore wrote, was “abhorrent, immoral, detestable, a crime against nature and a violation of the laws of nature and of nature’s God.” The state, he suggested, “carries the power of the sword, that is, the power to prohibit conduct with physical penalties, such as confinement and even execution” against gay couples.

In 2012, when campaigning for chief justice, Moore told an Alabama tea party rally that same-sex marriage would be “the ultimate destruction of our country because it destroys the very foundation upon which this nation is based.”

Federal attorneys in Alabama have repeatedly rejected Moore’s legal stance on gay marriage. Last July, a federal district judge in Mobile ordered Alabama judges to issue same-sex marriage licenses in accordance with the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic ruling.

“This issue has been decided by the highest court in the land and Alabama must follow that law,” U.S. attorneys Joyce White Vance of the Northern District of Alabama and Kenyen Brown of the Southern District of Alabama reiterated in a statement last week.

Moore scoffs at such criticism. “The United States Supreme Court does not make the law of the land,” he said. “The law of the land is the United States Constitution. They rule on cases from various circuits and their decisions are final in those circuits, but they’re not an automatic law.”

While he is accused of sowing confusion across Alabama, Moore maintains he is simply trying to clarify the law until the state’s Supreme Court, which has been deliberating for six months on the effect of Obergefell on its prior ruling, makes a decision.

Significantly, Moore’s latest order seems to have had little impact on the availability of marriage licenses throughout the state. According to the Montgomery Advertiser, only three probate courts reported stopping issuing marriage licenses last week. Most of the state’s 67 counties are issuing licenses to all couples.

To quote the Blues Brothers, he’s on a mission from God.

— Ronald Krotoszynski, University of Alabama law professor

While Alabama remains one of the nation’s most conservative states, there has been a gradual shift of public opinion on moral issues, including same-sex marriage and prayer in schools, said Gerald Johnson, a retired political science professor at Auburn University.

Nearly a decade ago, 81% of voters in Alabama passed a constitutional amendment prohibiting same-sex marriage. A 2014 American Values Atlas survey found that 59% of Alabamans opposed allowing gay and lesbian couples to marry legally.

“Generally, voters are drifting away from where Moore stands,” Johnson said.

Some political observers say Moore, who cannot be reelected as chief justice in 2018, might use his stance on gay marriage to position himself as governor.

Yet even if Moore’s position on gay marriage might serve him in a Republican Party primary, it could be a liability in a general election, Johnson said, noting that Moore had already lost gubernatorial campaigns in 2006 and 2010. “His views are not held widely or supported by the majority of Alabamians.”

Moore takes it all in stride. “I’ve been involved in many battles over the federal Constitution,” he said last week. “This is probably not the last.”

Jarvie is a special correspondent.

ALSO

Obama gives upbeat assessment of his presidency, and aims to have a say in who follows him

Poll shows majority in West opposes giving states control over federal land

In North Dakota, an oil boomtown doesn’t want to go bust

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.