100,000 in Tucson embrace Mexican approach to death with All Souls Procession

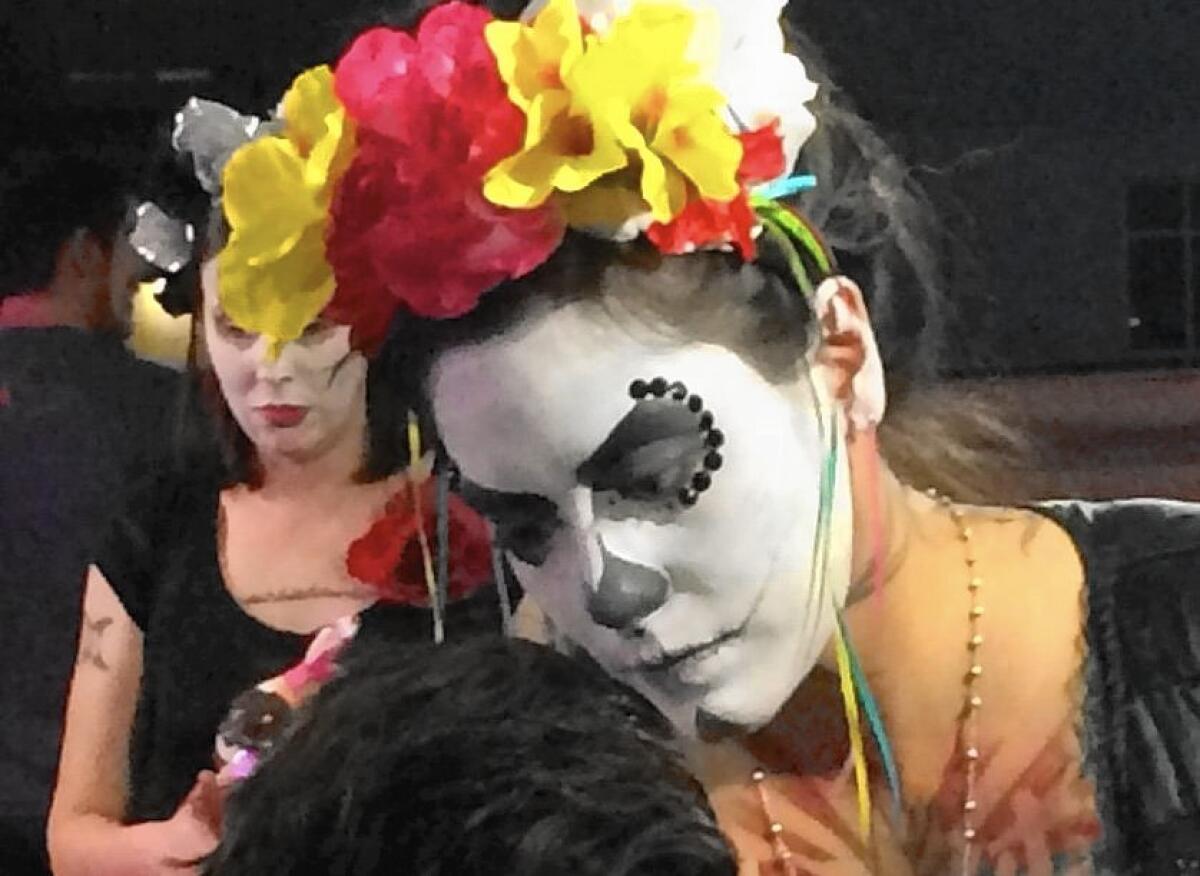

Many participants had their faces painted in the Dia de los Muertos style to resemble skulls.

- Share via

Reporting from TUCSON — We are forever in the midst of death, and yet we try to believe it doesn’t exist.

We put our dead in cemeteries and, when we pass them, we superstitiously hold our breath. We tell our children the dog has gone to a farm, that grandma is waiting, arms outstretched, in a sunny hereafter. We elide the notion of an ending, of death.

In Tucson, they choose something different — a parade.

The city’s All Souls Procession is adapted from Mexico’s Dia de los Muertos, a pre-colonial celebration of dead relatives meant to remember them and help them into the afterlife.

The idea for the Tucson procession is not nearly so old, and the notion of an afterlife is nowhere to be found. A Tucson local visited a village in Mexico in the late 1980s, and happened to arrive at the beginning of November, when the village was in the midst of Dia de los Santos and Dia de los Muertos, which honor saints and the dead.

“He was amazed at the different attitude toward death and life itself,” said organizer Jhon Sanders. “We don’t take a typical somber attitude toward death — that it has to be gloomy or it must not be talked about. This is all about a community dialogue about life and death.”

In 1990, inspired by the story about the Mexican village, a local artist named Sue Johnson walked the city with a memorial to her father. The next year, more people followed. This year, more than 100,000 people made a somber, orderly march from the city center to a public market, where a paper urn filled with scraps of memories from thousands of people was raised into the air.

Long after the sun went down, the urn was lit afire. In it burned the memories of convicts, stillbirths, braceros and butterflies. People came to mourn and celebrate.

This year, the theme was “the unmournable,” dedicated to memorializing people and things that society doesn’t always consider worthy of mourning.

Some people wore prison garb or photos of Mexican laborers. A procession organizer wore a black-and-white photo of a dying boy tied to a pole at a Florida prison camp in the 1930s. One woman mourned the endangered monarch butterfly.

Rachel Santay wore bull horns over a face painted like a decorative skull, known in Mexico as a calavera.

“I’m memorializing the bulls who died in bullfights in Spain,” Santay said. “They’re not mourned. Their deaths are celebrated in a sport. Death is a tapestry and they are a thread in it, and they deserve this.”

The procession, which took place Sunday, swayed its way through the streets as the last of twilight disappeared behind the mountaintops surrounding Tucson. Men and women in ragged Victorian outfits, their top hats tattered, their dresses decaying, made up most of the procession, which was flanked on both sides by onlookers who occasionally jumped into the procession.

There was no barrier separating the crowd and the procession, no corporate sponsorships and no visible police presence.

“This community takes care of itself,” Sanders said.

Many people took advantage of free face-painting, applying white makeup to cover their faces and black paint to signify the eyes and mouths of a skull.

Aeni Domme, a Phoenix makeup artist, is used to doing late-October costume makeup for Halloween events.

But the Tucson procession is much more personal. She wore navy blue makeup this year, a favorite color of a friend who had died.

She spent most of the morning and afternoon dipping in and out of rooms at the Hotel Congress, a central hotel on the route, applying fine detail work to an eyebrow or cheek. She was busy with customers, who paid $150 for their makeup, most of the day.

More than one hour was spent in one woman’s room as the woman tried to convey the design and look she wanted. Domme tried to probe her motivation, asking who she was memorializing and why.

The procession is a public display of intensely personal feelings, and Domme was reminded of this by the woman’s response. “She took a while to think about it,” Domme said. “Then she just said, ‘None of your damn business.’”

The procession also included hundreds of children. Children in painted faces, children in Halloween costumes, children carried atop shoulders, laughing children, crying children and kids who fell asleep. Some of the imagery was graphic, and some of the costumes were realistic depictions of death.

“Death is not something we should run from,” Sanders said. “It’s only a monster under the bed if you don’t talk about it.”

Twitter: @nigelduara

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.