Government shutdown is no idle threat

WASHINGTON — Outside the capital the prospect might seem unthinkable, but inside it seems increasingly likely, and to some inevitable: In less than two weeks, the federal government, from the Agriculture Department to the Weather Service, may shut its doors.

Agencies already have contingency plans for stopping all but essential work. Soldiers would be required to report for duty but would not be paid. National parks would be closed and overnight campers would be given two days to leave. Social Security checks would go out, but the agency would stop updating people’s earning records. The State Department would stop issuing most passports.

The last time the entire government shut down, for five days midway through the Clinton administration, about 800,000 federal employees were furloughed without pay. A second shutdown a few weeks later lasted 21 days but affected only part of the government. Workers eventually were reimbursed, but the government has made no guarantee that would happen again.

Now, as then, the shutdown looms because a political standoff has blocked passage of the annual bills that provide money for most government agencies.

The opening round of the fight comes Friday with a vote in the House. The budget year ends Sept. 30.

The snarl this time is worse than in the Clinton era in at least two ways: It involves not just one deadline, but a series of deadlines over the next several weeks, any one of which could see normal government activities come to a halt. If Congress manages to slip past the end of the budget year, the next crisis will come when lawmakers face a vote in mid-October on raising the limit on the nation’s debt.

Moreover, the fight has morphed from a straightforward battle between Republicans and Democrats into a three-way brawl in which the GOP congressional leadership must contend not only with the White House, but with conservative insurgents in their own ranks.

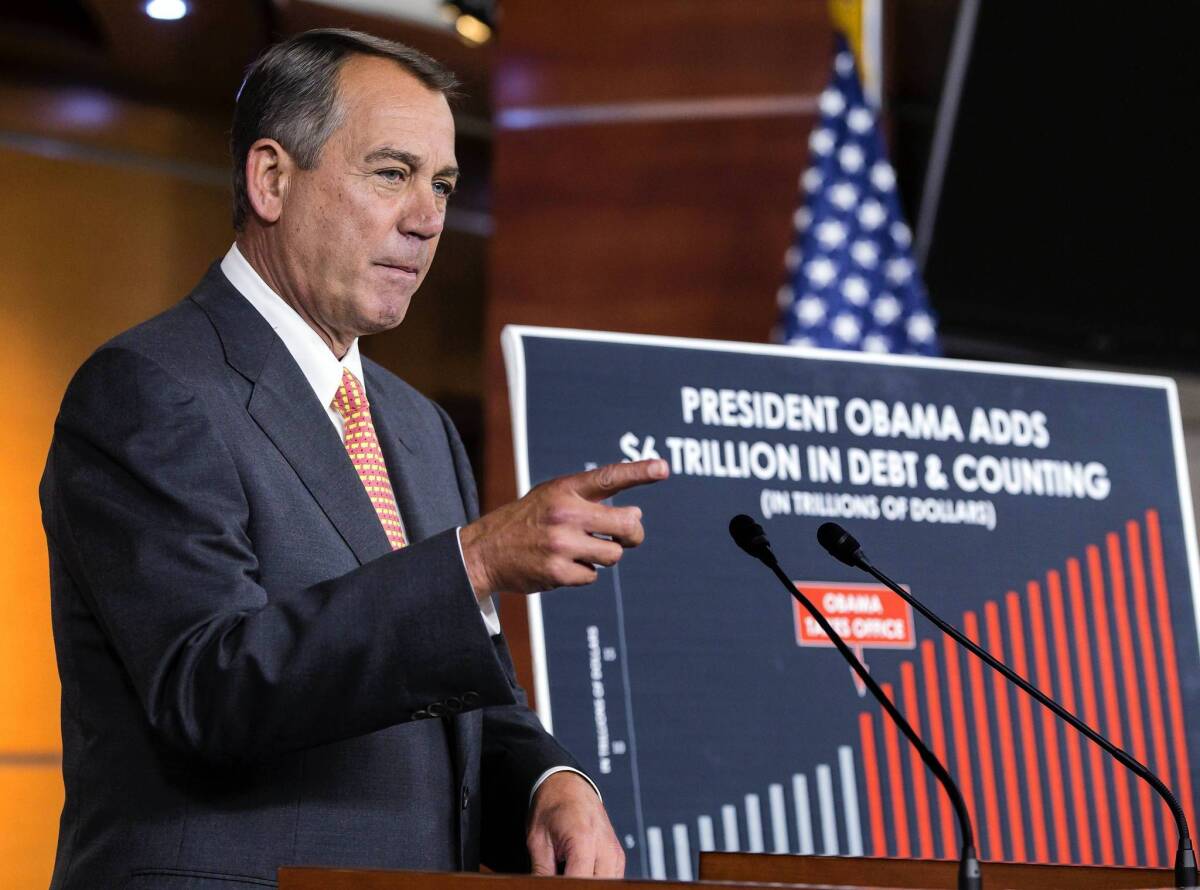

House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) presides over an uneasy coalition of Republican regulars and tea-party-backed conservatives. The conservatives, rallying to the demand to “defund Obamacare,” have insisted that the GOP refuse to keep the government financed unless the White House and the Democratic majority in the Senate agree to block President Obama’s healthcare law. The administration plans to roll out new online health insurance marketplaces — a key part of the new law — on Oct. 1.

Obama repeatedly has said he will not renegotiate the health law. Last year’s presidential election and the Supreme Court ruling that upheld the Affordable Care Act resolved its fate, he says.

His Democratic allies have stood with him. “I want to be absolutely crystal clear: Any bill that defunds Obamacare is dead — dead,” Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) said Thursday. “It’s a waste of time.”

Boehner and his leadership team, as well as many Senate Republicans, have wanted to avoid the fight, fearing that if government work stops, angry voters will blame Republicans, as happened in the back-to-back shutdowns in 1995-96.

“Most of the people who are doing this are new and did not have the experience that we had when the American people, who don’t like government but don’t want it to be shut down, reacted in a very negative fashion,” Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) said in a CNN interview Thursday.

White House officials appear to share that view, and Obama in recent days has sometimes seemed to be almost goading Republicans into a confrontation. Officials also say the splits within the GOP have complicated the process.

“Right now, there is a ‘conversation’ within the Republican Party, and I use that as a polite word,” Sylvia Mathews Burwell, director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, said in an interview Thursday.

The tea party conservatives, by contrast, argue that the public dislikes the healthcare law and will blame the president for refusing to sacrifice it. Others believe Obama was weakened by his handling of the chemical weapons crisis in Syria, and will back down in a fight.

“I wasn’t here in 1995. But that was the last century,” Rep. Tim Huelskamp (R-Kan.) said Thursday.

“What’s changed since then,” he continued, “is we have the most unpopular bill in modern history sitting right before us. An overwhelming majority of Republicans oppose it, and most independents.”

The gap between the Republican factions looms wide, both in Congress and back home. Asked about the healthcare law in a recent Pew Research Center poll, almost two out of three Republicans who identify with the tea party said that they wanted lawmakers to “do what they can to make the law fail.”

Among Republicans who do not identify with the tea party, only one-third took that position, with 44% saying they wanted lawmakers to “do what they can to make the law work as well as possible.” Among the public as a whole, nearly 7 in 10 either supported the law (42%) or disliked it but wanted lawmakers to make it work (27%), the poll showed.

Traditional Republican allies also have warned against a shutdown. “It is not in the best interest of the U.S. business community or the American people to risk even a brief government shutdown” that could send new “uncertainties washing over the U.S. economy,” the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s chief lobbyist, Bruce Josten, recently wrote to lawmakers.

But tea party groups have big sway in many Republican congressional districts. And the “defund Obamacare” campaign has become a major rallying cry and fundraising tool for groups on the right, some of which have threatened to finance primary challenges against GOP lawmakers who buck the cause.

Faced with those pressures, Boehner earlier this week yielded to the demands from his right and agreed to bring a bill to the floor that would fund the government but block money to implement the healthcare law. If it passes, as expected, the measure will go to the Senate, where it is all but certain to be rejected, probably late next week. That would leave Congress stalemated as the deadline approaches.

Boehner seems to hope that at that point conservatives would relent, allow a money bill to pass and push the confrontation off until the debt ceiling deadline. GOP strategists think they would have greater leverage with the White House with the threat of a default that could damage the economy.

But throughout the year, Boehner and his leadership team have misjudged the willingness of the most conservative Republicans to go along with the leadership’s plans. Some are tired of postponing the battle. Some fear the GOP leadership will abandon them in a higher-stakes standoff over the debt ceiling. They believe they would do better to fight now, not later.

Either way, economists warn that if a shutdown happens, the U.S. economy will suffer, particularly if it goes on a while.

“The effects build over time,” Douglas Elmendorf, the head of the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, told reporters at a breakfast this week sponsored by the Christian Science Monitor.

“Two weeks is worse than one week, and three weeks is still worse than two weeks, and four is still worse than that,” he said.

Michael A. Memoli and Christi Parsons in the Washington bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.