Is Ohio case of migrant youth trafficking evidence of a ‘systemic problem’?

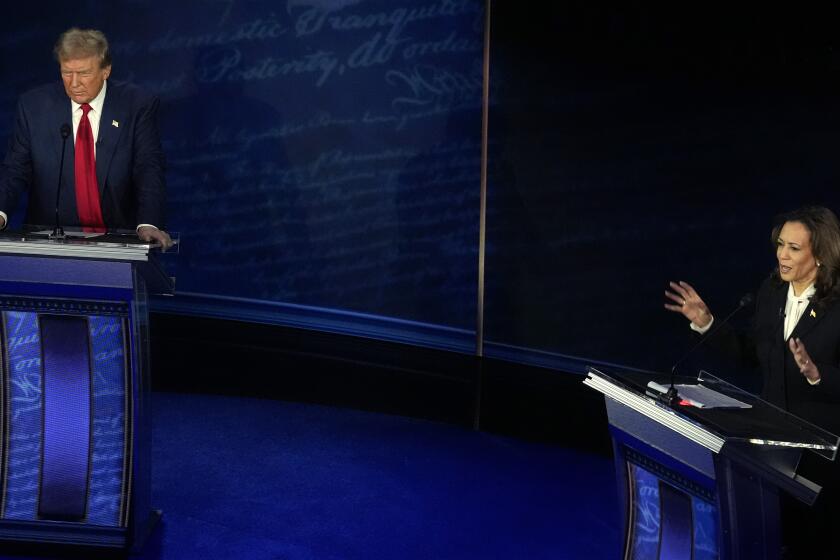

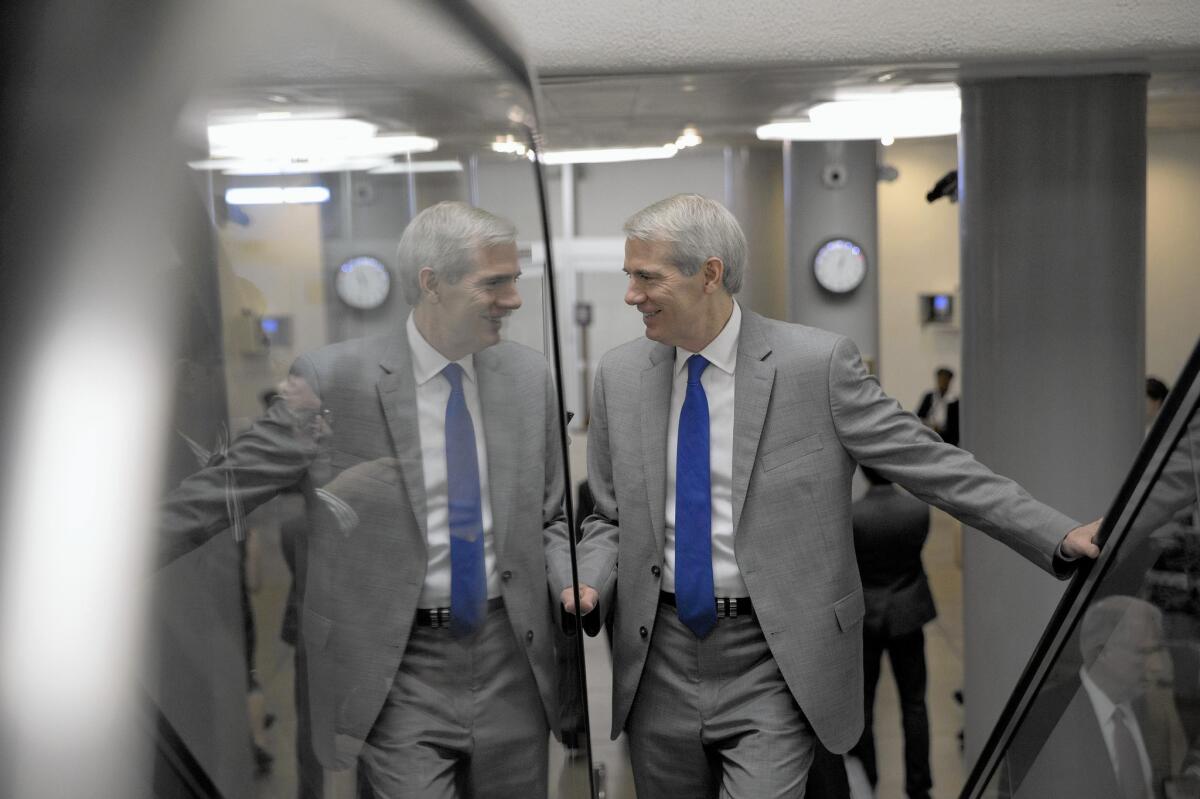

Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), chairman of the Senate’s subcommittee on investigations, is leading the inquiry on how six human trafficking suspects were able to pose as sponsors for a group of Guatemalan youths, who were then forced into labor.

- Share via

The basics of the Trillium Farms case are shocking enough:

Human traffickers lured half a dozen teenage Guatemalan boys to central Ohio with the promise of schooling, prosecutors say, then confined them to dilapidated trailers and forced them to work 12 hours a day at an egg farm, confiscating their paychecks and threatening to kill them if they sought help.

But also shocking is how the youths ended up there:

The federal government had placed the teens with the traffickers, who had posed as relatives and family friends to take responsibility for the boys.

Now, congressional lawmakers are investigating how the Ohio traffickers and others managed to take advantage of a federal program intended to place young migrants with sponsors while their immigration cases are pending.

“Based on what I’ve learned to date, I am concerned that the child placement process failure that contributed to the Ohio trafficking case is part of a systemic problem rather than a one-off incident,” said Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), who is leading the inquiry as chairman of the Senate’s permanent subcommittee on investigations.

“We continue to demand answers from the administration with the goal of uncovering how this abuse occurred and reforming the system to protect all minors against human trafficking,” Portman said.

The Border Patrol turns over unaccompanied minors to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which places them at shelters, then with parents, relatives or other qualified sponsors.

Advocates for immigrants have complained that the sponsor system lacks much-needed oversight and follow-up, and that problems worsened with an influx of more than 68,500 unaccompanied minors mostly from Central America coming across the southern border in 2014. Recent months have seen another jump in the number of migrant children entering the country illegally or applying for asylum. There were 4,476 unaccompanied children caught on the southern border in September alone.

In the fiscal year that ended in September, more than 40,000 unaccompanied youths arrived in the U.S., and more than 27,520 of them were placed with sponsors. More were placed in California than any other state — 3,756.

Of the 16,503 unaccompanied minors whose immigration cases were closed last fiscal year, about half were ordered deported, most because they failed to appear in court — 7,171.

Federal officials do not track whether sponsors ensure youths show up for court and are not required to provide follow-up services. State child welfare agencies are not required to notify federal authorities of alleged abuse or neglect by sponsors.

But the Office of Refugee Resettlement does maintain a database that allows staff to track sponsor names, addresses, assessments, and the number and names of unaccompanied children they have tried to sponsor, according to agency spokesman Mark Weber.

We continue to demand answers from the administration with the goal of uncovering how this abuse occurred and reforming the system to protect all minors against human trafficking.

— Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio)

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Troubles with sponsors had emerged before Trillium Farms.

In 2013, the agency issued an alert warning of three “fraudulent sponsors” with addresses in Colorado, Iowa and Minnesota seeking to claim unrelated unaccompanied minors.

Then last year, Guatemala-based traffickers conspired to bring the six Guatemalan youths — ages 14 to 17 — to Trillium Farms, according to an indictment unsealed this summer. They forced the youths to work even when they were injured, confining one who complained to a trailer without a bed, heat or toilet, the indictment alleges.

When the youths failed to appear at immigration court in Cleveland, officials began an investigation that resulted in a raid at their trailer park about 50 miles north of Columbus in rural Marion, Ohio, last December.

According to the indictment, the traffickers and their associates had posed as friends of the boys’ families and submitted paperwork to the Office of Refugee Resettlement to become sponsors. Afterward, the indictment said, some of the suspects lied to investigators and threatened a witness to lie, too.

Six were charged with labor trafficking, conspiracy, witness tampering and related immigration offenses. One is a U.S. citizen and five are foreign nationals from Guatemala and Mexico, including one woman.

Two pleaded guilty. One was sentenced to time served and deported, another to a year in prison and then deported. A pair pleaded guilty and await sentencing. Another pair’s cases are pending.

Steven Dettelbach, U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Ohio whose office is prosecuting the cases, declined to comment about how refugee resettlement office failed to detect the traffickers.

“These traffickers are predators, and they are very good at exploiting weaknesses these victims may have,” said Dettelbach, who prosecuted the notorious El Monte Thai sweatshop trafficking cases in Southern California in the 1990s. “If you ask for your paycheck and you get hit, what’s going to happen if you go to the police?”

The Guatemalan youths were returned to federal custody and transferred out of state, and it’s not clear what happened to their immigration cases, immigrant advocates said. Weber said he could not discuss the cases, citing privacy concerns.

Office of Refugee Resettlement officials said last year they were already taking steps to better safeguard the sponsor system.

They started 30-day, post-release “wellness checks” of children and sponsors by phone, contacting 1,441 as of September. Among other efforts, the agency also added child abuse and neglect registry checks on all non-relatives and distant relatives seeking to be sponsors.

Some lawmakers and immigrant advocates say more oversight is needed.

The federal resettlement office “is trying to put these practices in place, but they are highly imperfect,” said Maria Woltjen, director of the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights in Chicago.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Nov. 18, 10:28 a.m.: This article took a quote by Maria Woltjen, director of the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights, out of context. Woltjen did not say that more oversight is needed of the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement. When she said that certain practices “are highly imperfect,” she was referring to all child welfare systems, not the federal agency.

------------

Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas), who represents the Rio Grande Valley, where many unaccompanied migrant youths cross the border, wants the resettlement office to conduct biometric screening of all sponsors. DNA testing is currently used to confirm sponsor relationships “in limited circumstances,” Weber said, and the agency has not ruled out biometric testing.

The role of sponsors — and the failure of youths to appear for immigration hearings — gained attention this fall after some unaccompanied youths were arrested in connection with the Sept. 4 killing of Danny Centeno Miranda, a 17-year-old Salvadoran migrant living with relatives in northern Virginia.

The death of Centeno Miranda, who also had entered the country illegally, led Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa) to investigate.

On Oct. 23, Grassley wrote to Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson, noting that the month before the shooting, the suspects had failed to appear in immigration court. Grassley demanded information about their immigration cases, including whether their sponsors were screened and held accountable when the youths didn’t show at court.

Last week, the suspected shooter, a 17-year-old Mexican national, was indicted on murder and associated charges. Two men from El Salvador, ages 20 and 18, were indicted as accessories. All three have ties to the Mara Salvatrucha gang, also known as MS-13, authorities said.

“Had these suspects appeared for their mandatory court date, they would have likely not had the opportunity to murder a 17-year-old high school student,” Grassley wrote. “It is clear that the federal government has failed in its role to prevent great risk to the public safety.”

Grassley had yet to receive a response Friday.

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

Twitter: @mollyhf

ALSO

Hawaii struggles to deal with rising rate of homelessness

In protest over gay rights, Mormons give up their church membership

Florida cemetery visitor has birdwatchers all aflutter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.