Rosa Parks documents reveal the fury behind the image of stoic protester

- Share via

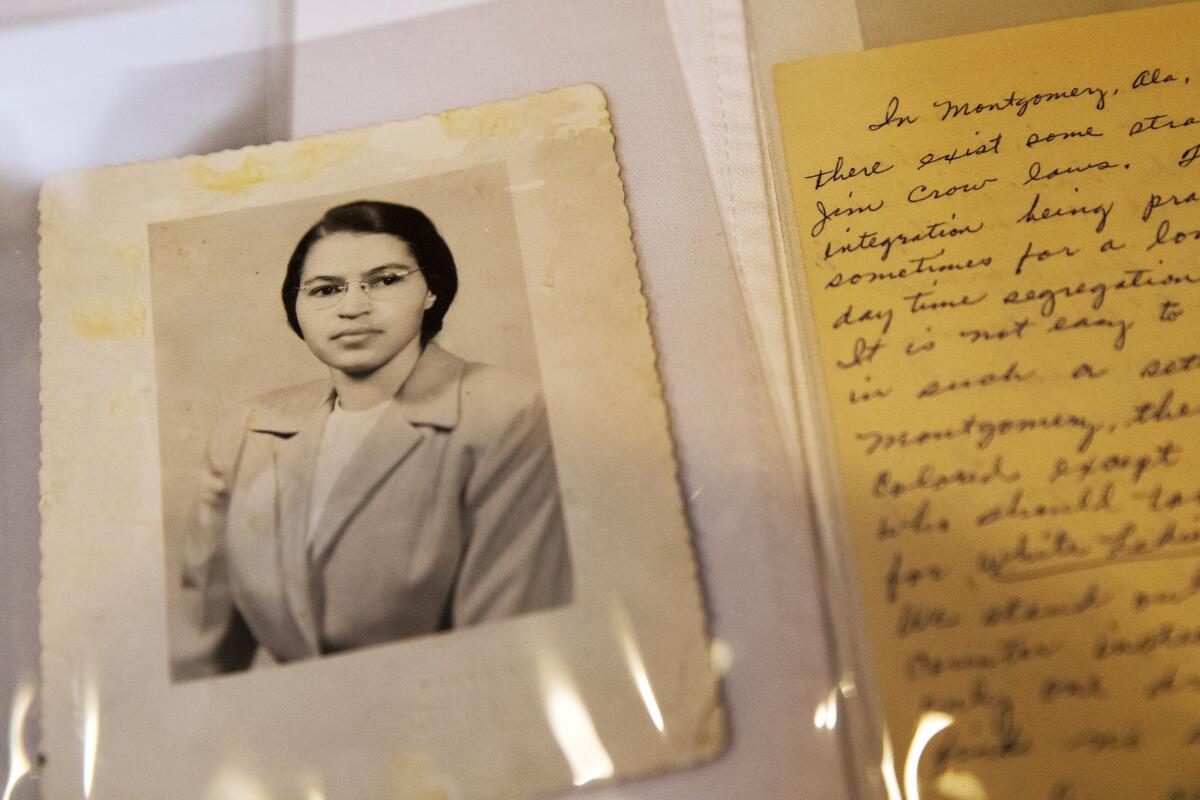

Reporting from Washington — The black-and-white photograph of Rosa Parks on the bus looks familiar.

She’s staring forward, reenacting her moment in history as if preparing for a place in a grade school textbook on the civil rights movement, conservatively dressed in a hat and patterned dress, holding her handbag tightly on her lap so as not to bother anyone.

But her words, written in her journals and letters at roughly the same period as her 1955 arrest, show a far more provocative and wounded Parks, who sees the daily humiliations of segregation in Montgomery, Ala., as soul-crushing, to the point that “the line between reason and madness grows thinner.”

“Such a good job of ‘brain washing’ was done on the Negro, that a militant Negro was almost a freak of nature to them, many times ridiculed by others of his own group,” she wrote.

Both versions of Parks’ persona — the stoic protester and the furious agitator — are revealed in intimate detail in a newly released trove of documents that includes 7,500 manuscripts and 2,500 photographs collected throughout her long life.

The collection, which had been stored in a warehouse amid an estate battle, is on loan to the Library of Congress for the next decade, as part of an agreement with the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, which bought it last year.

The public will have access to the collection beginning Wednesday, which would have been Parks’ 102nd birthday. Parks died in 2005 at age 92.

The journals detail her daily life as a seamstress in the Montgomery Fair department store, where black employees were forced to eat lunch up against the bathroom designated for black employees and patrons. They show her raw anger at the killing of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi, less than four months before Parks’ arrest, a slaying “that could be multiplied many times in the South.”

The diverse documents in the collection, kept in Mylar slips and acid-free folders, one by one create a mosaic of a life and a movement: A peanut butter pancake recipe scribbled on the back of a bank envelope. A program for a brunch honoring radical professor Angela Davis, whose defense on murder charges she supported.

There are postcards from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a worn Bible with a Spanish-language flashcard used as a bookmark, and a badge in her name for the Mississippi Freedom Summer voter registration drive of 1964.

“The icon Rosa Parks as mother of the civil rights movement — as shy, genteel, working-class black woman — it was the public persona she thought was important to maintain because of the tenor of the times she lived through,” said Adrienne Cannon, African American history and culture specialist for the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. “But in this collection, we hear more of that militant voice.”

Cannon said that she believed Parks — whose political activism was better understood among civil rights activists and historians than the general public — wanted history to see her in a more complex light, and that the papers were maintained as a sort of time capsule, for a day when more of her edges could be understood.

“She held onto them until the end of her life, the most personal of the personal, because she wanted us to know the true Rosa Parks,” Cannon said.

The narrative begins at an early age, when Parks recalls her fear as a 6- or 7-year-old, “keeping vigil with my grandpa” who stood watch with a shotgun to protect their rural Alabama home from the Ku Klux Klan.

“I wanted to see him kill a Ku Kluxer,” she wrote.

Parks was already an activist — influenced by her husband, her grandfather and an Alabama civil rights group known as the Women’s Political Council — by 1955, when she refused to give up her seat on the bus for a white man, archivists said.

“I had been pushed around all my life and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it any more,” she wrote on yellow paper, full of the scratched-out words and addenda of someone who is thinking how her words might be viewed later. “When I asked the policeman why we had to be pushed around? He said he didn’t know. ‘The law is the law. You are under arrest.’

“…There is just so much hurt, disappointment and oppression one can take.”

The artifacts show Parks’ deep involvement in the 13-month bus boycott that followed her arrest.

For example, the front of a datebook from Montgomery Fair shows a Hallmark logo, a butterfly and pink flowers — a 1950s rendering of aspirational leisure. Yet Parks transformed the datebook into a tool for the movement. On the back, she jotted names of carpool drivers needed to subvert the bus system during the boycott, which ended when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in her favor that segregated public buses were not constitutional.

Some objects combine the ordinary with the historic. A 1956 letter addressed to Parks’ mother tells of a trip to New York, before a rally at Madison Square Garden.

“The people here are very nice,” Parks wrote. “I spent Thursday night with Mr. and Mrs. Thurgood Marshall,” when the future Supreme Court justice was chief counsel of the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

A 1957 memo from civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin gives her talking points for a speech at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, an event held at the Lincoln Memorial that helped vault King onto the national stage. Like others in the cache, the document shows the careful plotting of the movement at the granular level.

“It would be good if you point out what it means to the ‘freedom fighters’ to act in common with those who defend justice in the north,” Rustin wrote.

Parks, who lost her job after her arrest, moved with her husband to Detroit in 1957 and did not find steady employment until 1965, when she began working for Rep. John Conyers Jr. (D-Mich.).

As the years went on, her iconic status grew. Documents from her later life include a photo with Pope John Paul II, a scrapbook from her visit to Japan, and the certificate for the Presidential Medal of Freedom, signed in 1996 by President Clinton.

She never had children, but later in her life received birthday cards from students all over the world, including a batch she kept from the Prairie View Intermediate School in Texas sent in 2000.

“Dear Mrs. Parks,” wrote Zack, in orange crayon on green construction paper. “I think what you did for African Americans is great. Was it scary to go to jail?”

Twitter: @Noahbierman

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.