Overcrowded, unsanitary conditions seen at immigrant detention centers

- Share via

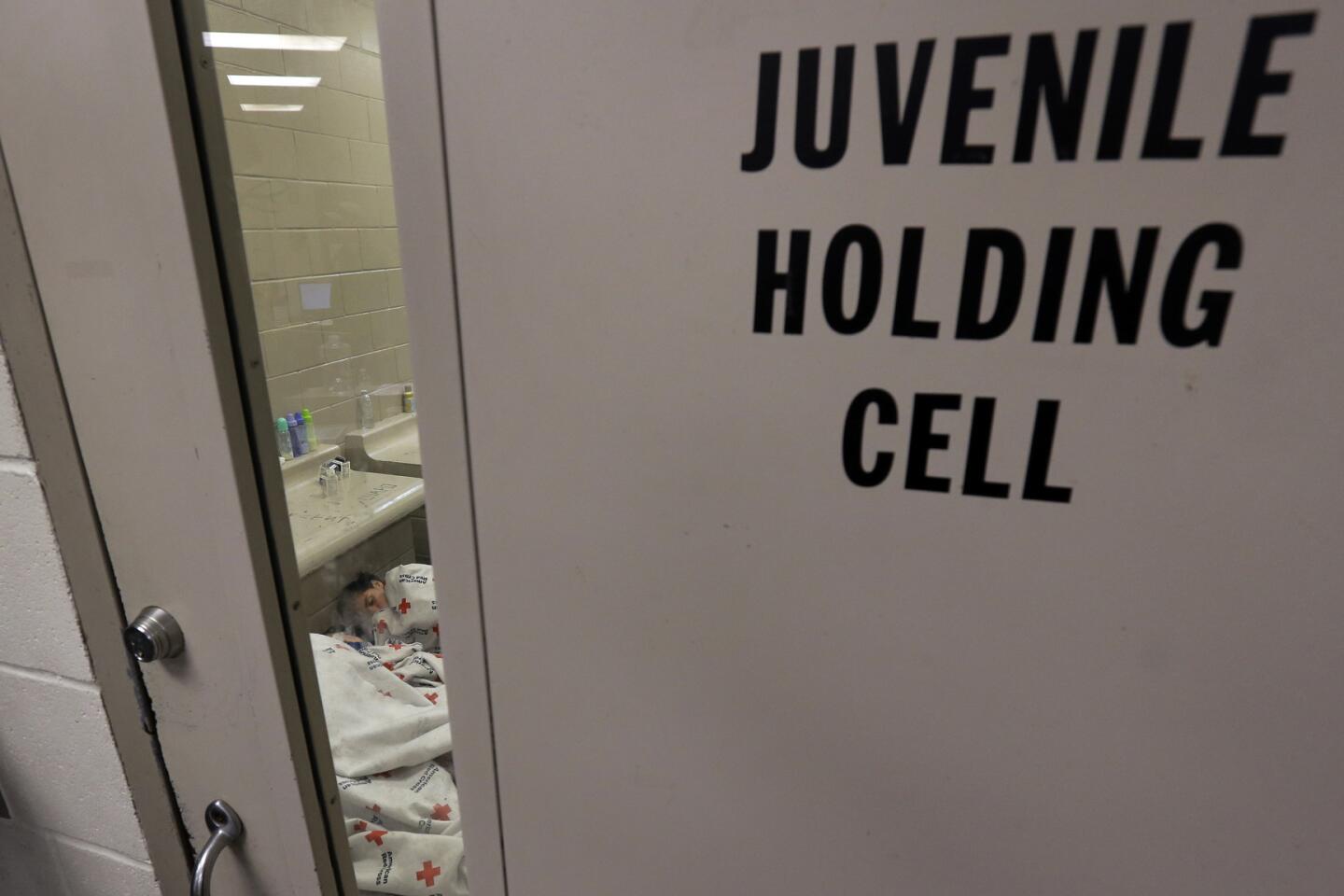

Reporting from Brownsville, Texas — Immigrant youths covered the dirty concrete floors of the Border Patrol holding cells here, sprawled shoulder to shoulder and draped in grubby Red Cross blankets, enveloped in a haze of sweat and body odor.

Groups of girls and boys stared out the windows of their cells, some of the girls holding babies of their own, as agents watched from a central monitoring station. A girl could be seen scrubbing her armpits at the back of the cell.

This 4,900-square-foot detention center near the Mexican border in south Texas was built to house 250, but for the last few months it has been holding twice that, thanks to what U.S. officials say is an unprecedented influx of children and families, most from Central America, hoping for refuge in the United States.

More than 800 of the youngsters are being held at a former warehouse in Nogales, Ariz., now also deployed as a detention center for migrant youths.

Facing growing controversy over reports of crowded and unsanitary conditions, Border Patrol officials on Wednesday provided the first limited public access to the two facilities, allowing reporters on brief, controlled tours for glimpses of children and a few mothers detained there at the end of their often long journeys from places as far away as Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

In Arizona, most were corralled behind chain-link fences topped with razor wire, huddling for warmth on plastic mats under flimsy metallic Mylar blankets. A television was suspended from the ceiling. Banks of portable toilets served as sanitary facilities. Beside a recreation area, a camouflage tarp had been strung up to shield temporary showers.

In Brownsville, the group included young mothers, many of whom looked exhausted. Some of the children looked dazed or stared blankly from the cells, while others waved and smiled. Many slept.

In Nogales, children clung to the towering chain-link fences around their cells, staring at visitors. Some appeared to have been crying, with swollen and red eyes. Others simply stared.

Immigrant advocates say the latest images of overcrowded cells and dirty floors reinforce their concerns that U.S. Customs and Border Protection is ill-prepared for the influx and is not properly safeguarding immigrants rounded up along the border.

“The agency has not been especially consistent in affording access or broad access to these facilities. The lack of oversight and transparency is part of what has allowed these abuses to continue. This current situation is a recipe for abuse of vulnerable children,” said James Lyall, staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, which filed a complaint last week with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, calling conditions at the stations “inhumane and inadequate.”

Since October, 47,000 children have been caught crossing the southern border without parents or other family members, a more than 90% increase from last year, federal officials said. The number of unaccompanied children caught could reach 90,000 this year.

Reporters on Wednesday’s tours were not allowed to interview youths or adults held at the stations, nor could they talk to Border Patrol or Federal Emergency Management Agency staffers. A single photographer-videographer was allowed to share images captured at each station.

In Brownsville, two FEMA staffers could be seen leading a few girls out of their cell to a concrete bench. A girl in a blue Aeropostale shirt ran her fingers through her hair, rumpled from sleeping on the floor. She smiled at the FEMA men.

“Hola,” one of the men said to the group, then paused, turning to his colleague. “Shower — I’m trying to think what to say. How do you say ‘shower’?” the man said.

The girls stared back at him, uncomprehending.

The surrounding Rio Grande Valley is the epicenter of the influx.

Youths and families are sent to Brownsville from two other nearby Border Patrol stations after being screened for diseases by U.S. Coast Guard staffers. By law, they are supposed to be transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services within 72 hours, but the Border Patrol says it is struggling to meet that requirement.

From here and the facility in Nogales, they are transferred to longer-term Health and Human Services shelters opened elsewhere in Texas, as well as in California and Oklahoma.

Eventually, they will be placed with parents, relatives or other approved sponsors in the U.S. to await the outcome of their immigration cases.

The 120,000-square-foot facility in Nogales can now house 1,500 children at a time in nine holding cells, segregated by age and sex, officials said.

There, a group of about 60 boys ages 13 to 15 attempted to sleep, play Frisbee or watch the television perched above their holding cell, which reeked of sweat.

Outside, about two dozen young girls lined up to play hula hoop, catch and racquetball. A girl in a blue Miami Dolphins sweat shirt jumped rope.

Art Del Cueto, president of the local Border Patrol union, said children here had told him they were urged to migrate illegally now by family members, smugglers and religious leaders who believed they would be allowed to stay legally.

He said a child recently turned himself in to authorities at the border here by saying: “I’m Guatemalan. Please take me to your center.”

Border Patrol officials in Brownsville called the situation a “humanitarian crisis,” echoing President Obama’s comments in recent days, when he directed federal agencies to address the influx.

Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson is expected to visit the Brownsville station Friday, his second trip to the valley in as many months.

Vice President Joe Biden is traveling in South America this week and added a Friday stop in Guatemala to meet with Central American officials to discuss the immigration crisis.

Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) and Rep. Henry Cuellar, a Democrat who represents the valley, sent a letter to Johnson on Wednesday demanding answers to a slew of questions about the flow of young migrants and what’s being done to stop it.

“We ask that you work with us to [assure] the American people that your Department has achieved control of this humanitarian crisis by providing prompt responses,” they wrote.

Cuellar toured the McAllen Border Patrol station in Texas last weekend and has been meeting with Mexican and Central American diplomats to address the crisis.

He said the problem would not be solved on the border but rather at its source, in Central America, where the latest wave of young immigrants must be prevented from starting the trek north. “If we keep playing defense on the 1-yard line — which is the U.S.-Mexico border — you can see what’s happening,” he said.

An internal Border Patrol study, based on interviews with 230 migrants detained in the valley, found the immigration had been driven by violent conditions in Central America and by widespread erroneous reports that a new U.S. law allows women with children to secure a permiso, or pass, to stay in the U.S. indefinitely.

“A high percentage of the subjects interviewed stated their family members in the U.S. urged them to travel immediately, because the United States government was only issuing immigration ‘permisos’ until the end of June 2014,” the report said.

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

@mollyhf

cindy.carcamo@latimes.com

Hennessy-Fiske reported from Brownsville and Carcamo from Nogales.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.