The earthquake that toppled Eric Cantor: How did it happen?

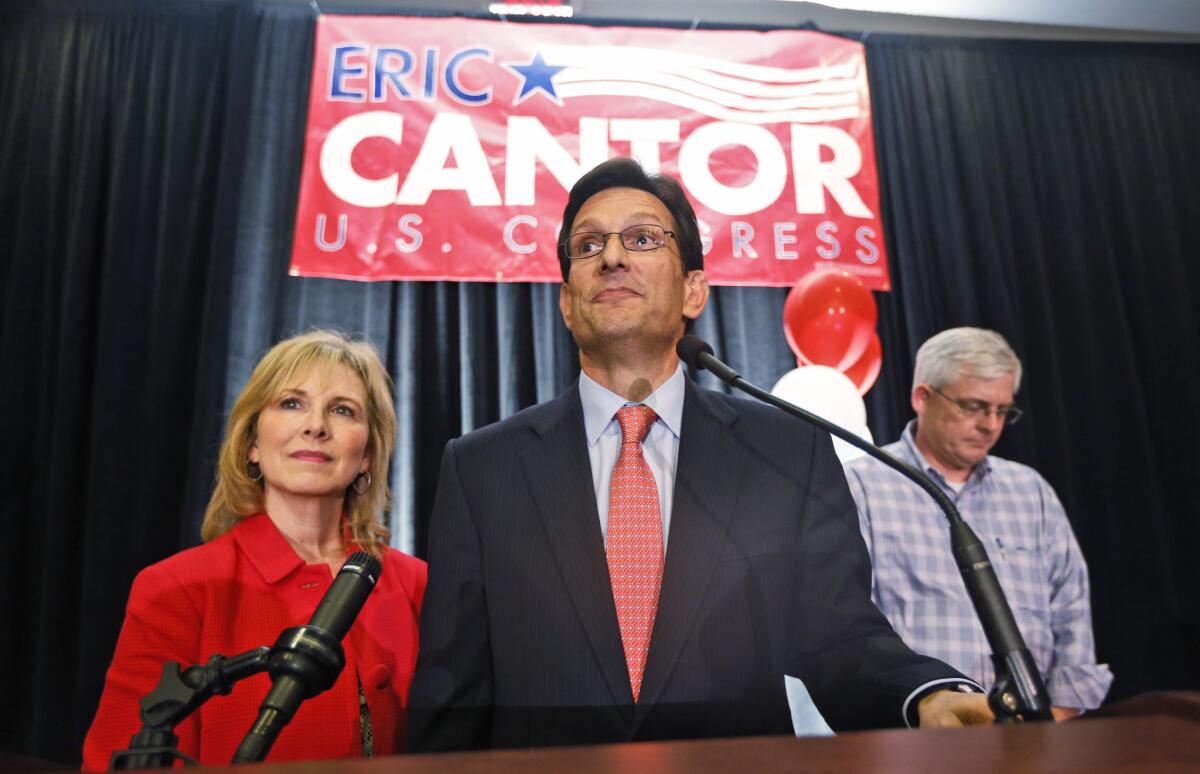

House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-Va.) delivers his concession speech in Richmond on Tuesday.

- Share via

One of the greatest political upsets of modern times occurred Tuesday in Virginia, when Eric Cantor was toppled by an insurgent GOP rival as he bid for an eighth term. Independent political analyst Stuart Rothenberg, not one given to hyperbole, said the result was “like an asteroid ha[d] fallen from the sky and hit the Capitol.” Others, not least Cantor, were similarly shocked.

Who is Eric Cantor?

Rep. Cantor of Virginia is the No. 2 Republican leader in the House of Representatives, making him one of the most powerful lawmakers and a prominent spokesmen for his party in Washington. As majority leader, a key responsibility is deciding, along with the speaker and others in the GOP leadership, which bills to bring to the House floor for debate. But even as they work together, Cantor has had an uneasy relationship with Speaker John A. Boehner of Ohio, often staking positions to the speaker’s right and aligning himself with the more conservative, less-compromising “tea party” wing of the Republican Party.

Why was Cantor’s defeat such a shock?

For several reasons. His leadership role gave him access to millions of dollars in campaign funds, allowing Cantor to vastly outspend his little-known opponent, David Brat. He ran more than 1,000 TV spots, compared with fewer than 100 for Brat. Also, because of his tea party sympathies, he was not seen as vulnerable to the sort of right-flank challenge that other Republicans have faced this primary season. Adding to the surprise, many of those Republicans beat back their tea party challengers. No serious election handicapper gave Brat any shot at winning. Even his campaign manager said he was surprised.

How often is someone in Cantor’s powerful position defeated?

It is exceedingly rare. Cantor, now in his seventh term, is the first House majority leader to lose a primary since the position was created in 1899. In 1994, Democrat Tom Foley of Washington became the first House speaker defeated at the polls since 1860.

What about the polling in Cantor’s race?

The Cantor campaign trumpeted a late May survey showing the incumbent crushing Brat by more than 30 points. But polls conducted for a candidate and passed on to the media are often more akin to a promotional advertisement than a legitimate sampling of voter opinion. Even the best, most impartial poll is subject to guesswork as to who will actually turn out to vote. Since no one saw Cantor facing serious competition, there was no outside pre-election polling conducted in the Richmond-area district, and Brat’s victory, as a result, seemed to come out of nowhere.

Who is David Brat?

Brat, 49, teaches economics at Randolph-Macon College, a small liberal arts and sciences college in Ashland, Va. His areas of academic specialization include macro-growth economics, international trade and finance, history and ethics. A political novice, he ran his campaign on a proverbial shoestring, raising about $230,000 to Cantor’s $5.7 million. Having handily won the primary, 56% to 44%, Brat appears well positioned to win in November in the heavily Republican district, which spreads over 100 miles from Virginia’s Tidewater region to the exurbs outside Washington. His opponent, as events would have it, is a fellow Randolph-Macon professor, Democrat Jack Trammel. He teaches sociology, with a focus on disability studies.

Why did Cantor lose?

The immigration issue doubtless played an important role. Cantor favored a modest easing of immigration law, favoring a plan to grant legal status for people who came to the United States illegally as children. Brat called it “amnesty” — a rallying cry for opponents of comprehensive immigration reform, who favor an enforcement-only approach — and accused Cantor of being in “cahoots” with Democrats trying to push through an overhaul bill. But, at bottom Cantor seemed to lose touch with his district, spending much of his time and travels in pursuit of wider ambitions. He was generally considered the natural successor to Boehner and there was even talk of Cantor perhaps running for president.

How much of a role did the tea party play?

While local activists were an important spur to Brat’s success, the largest, most richly funded tea party groups stayed away from the contest. A few national talk radio hosts weighed in on Brat’s behalf, helping raise his profile outside the district.

Who will replace Cantor as House Majority Leader?

That will be decided by the Republican members of the House in a vote expected this month. A fierce competition is already underway. The No. 3 GOP leader, Rep. Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield, is next in line for the spot, but he will not win the job uncontested. Others interested include Rep. Pete Sessions of Texas, a former head of the GOP’s congressional campaign committee.

Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers of Washington, the No. 4 ranking Republican, was also viewed as a possible successor, but on Wednesday she released a statement saying that, after conversations with her family and “many prayers,” she would remain in her current post. The tea party wing is also weighing whether to put up its own candidate for majority leader.

Is Cantor’s defeat likely to echo much beyond Virginia?

There is always the danger of drawing too broad a conclusion from a major political event, especially in the immediate aftermath. But politicians don’t operate in a vacuum. At the least, Brat’s stunning upset is likely to hearten other long-shot candidates, Democrat and Republican, who think they, too, might be able to overcome formidable odds. It would also seem to greatly diminish the chance of major immigration legislation passing Congress anytime soon, given the perception — true or not — that Cantor’s position on the issue led to his defeat.

Looking ahead to 2016, it underscores the difficult path for any candidate seeking to accommodate an increasingly conservative Republican base without compromising his or her chances among the broader electorate in the general election. It was a task that tripped up Mitt Romney in 2012 and might give pause to prospective candidates like ex-Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, who has staked a relatively moderate stance on immigration, among other issues.

Twitter: @markzbarabak

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.