Schwarzenegger Story Gets Another Rewrite

SACRAMENTO — Maybe the make-or-break moment of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s governorship was the morning of Nov. 10, 2005, in his hotel suite across the street from the Capitol building.

He had just been walloped in the special election that he had thrust before voters, capping a year when he had fought to put in place a distinctly conservative agenda.

Prepping the Republican governor for a news conference, one of his aides urged a tough stance: Don’t apologize, don’t give ground.

Schwarzenegger did the opposite. He appeared before the cameras and conceded that he had screwed up and promised to start listening to the Democrat-dominated Legislature.

So began his political resurrection. From a nadir at which he was being compared with Jesse Ventura, the pro wrestler who flamed out as governor of Minnesota after one term, Schwarzenegger rose to be the front-runner in the Nov. 7 election.

His governorship has been a string of such moments: spontaneous decisions that have carried large consequences, for better and for worse. New to professional politics, he has been learning as he goes.

He has overreached; called officials “stooges” and worse; flip-flopped, wasted time and money. All in full view of California voters and in the face of enormous expectations that came with the historic 2003 recall election.

But over the last 11 months he has righted himself, relying on competitive instincts that told him if he was to survive he needed to drop the hubris and build a centrist government more in step with California voters.

It worked. His approval rating is up to 56%, according to the latest Los Angeles Times poll, a rise of nearly 20 percentage points in one year.

Schwarzenegger came to the job convinced he could master it -- much as he has everything else he’s tried. But the job nearly mastered him. Three years after taking office, he is, in fundamental ways, still figuring out what a governor is supposed to do.

His advisors say they still worry when he speaks in public, wondering if he’ll blurt out something that offends a constituency or torpedoes a policy position his administration spent months crafting. Others who have worked closely with him said they have no idea what to expect next if Schwarzenegger wins.

Will he be the combative partisan who, 168 times during 2005, railed about “special interests” corrupting Sacramento, according to transcripts of speeches and interviews?

Will he be the go-along moderate who has not once uttered that phrase in public this year? “Arnold 2.0” is how some aides now describe him.

Or is another reinvention in the works?

“I don’t know where the governor is going to go next year,” said Assemblyman Keith Richman, a moderate Republican from Northridge.

*

Few people reach high elective office with so little political experience. Schwarzenegger walked off the set of “Terminator 3” and into the recall election.

Campaign workers mined interviews he’d given as a champion bodybuilder and movie star, looking for the germ of a policy platform. He was tutored extensively in his Santa Monica office -- sessions his staff labeled “Schwarzenegger University.”

The cramming helped. Schwarzenegger retains information well and is adept at numbers, which he says he thinks about in his native German. When he grasps something, he utters a two-word acknowledgment: “Got it.”

But after he took office, his busy schedule slowed the schooling. And the gaps in what he understood about California government became painfully evident.

Marybel Batjer, the governor’s Cabinet secretary in his first year, said, “Yes, he needed more education, and if I could have done it better -- and I don’t know how we could squeeze more time out of him -- I would have had policy briefing time on his schedule weekly.”

First Lady Maria Shriver would, on occasion, call then-Chief of Staff Patricia Clarey. Her husband would come home at night with a stack of briefing papers, Shriver said, and realize in frustration that he was not getting everything he needed from the daytime briefings, according to one person familiar with the conversations.

There was an embarrassing moment in his first months in office when Schwarzenegger’s inexperience showed.

He often boasted about his negotiating skills. After years of haggling with Hollywood bosses over movie contracts, he was confident he could outwit Sacramento interest groups. But it wasn’t as easy as he supposed.

He sat down with officials from the California Teachers Assn., the powerful labor group, to discuss the complex spending formulas that drive the education budget. The governor hoped CTA would agree to concessions that might stave off deep budget cuts.

Schwarzenegger acknowledged to his staff at one point that he wasn’t in command of the details. But he plowed ahead, ultimately striking a deal with the union: CTA would forgo $2 billion owed to schools, in return for the governor’s promise to repay the money in coming years.

The agreement turned out to be politically costly. It was Schwarzenegger who had been outmaneuvered.

Facing a tight budget the next year, the governor broke the promise. He told the union that if he lived up to the bargain, it would mean drastic cuts elsewhere in government that he was unwilling to make. Union officials turned on him.

The governor hadn’t realized the commitment he’d made, said Peter Siggins, then Schwarzenegger’s legal counsel, who was taken aback by the agreement.

“I sat down with [another aide] and said, ‘Did we really agree to this?’ ” said Siggins, now a state appeals court judge in San Francisco. “I was surprised. It ... really boxed him in.”

The teachers union, once a friend, was now a dogged and well-funded enemy.

*

For all the stagecraft Schwarzenegger employs to make sure he appears in a flattering light, he tends to wing it when he grabs the mike. He says what feels right at the moment. But the spontaneity can backfire, and has.

In April, the administration prepared for an environmental summit in San Francisco. In defiance of his big-business supporters, the governor was going to call for emissions caps meant to curb global warming.

The day came. Schwarzenegger led a discussion that included business leaders unhappy about the plan. An official of a cement trade group objected that mandatory caps would be a burden to business.

Schwarzenegger began to waffle. Maybe it would be better to start “without caps,” he said. Aides cringed.

“It undercut the main message of the day,” said one administration official, requesting anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly.

Damage was done -- and Schwarzenegger had to undo it. The next day, in an appearance in Davis, he said emissions caps were “a great idea.”

In other ways, Schwarzenegger sounds like the most seasoned of politicians, saying one thing but doing another.

The day after winning the election in 2003, he said at a news conference that he would devote himself to the job full time: “There will be no time for movies or anything else.”

A month later, he quietly signed an agreement to serve as a consultant to and editor of the tabloid and muscle-magazine publisher American Media Inc., which would pay him an estimated $8 million over five years. He severed the arrangement after it was made public last year.

Schwarzenegger once eloquently warned of the danger of “special interests” -- moneyed groups whose fortunes depend on state action. They give millions to politicians and expect favors in return, the governor said.

But since entering the recall campaign, Schwarzenegger has accepted record sums of campaign cash -- more than $114 million -- from oil companies, insurers, developers and growers that rely on the governor to sign or veto key legislation.

Every year the California Chamber of Commerce, the state’s leading business lobbying group, puts out a list of what it calls “job killer bills” -- legislation it wants defeated.

Of 11 such bills that passed the Legislature and made it to the governor’s desk this year, he vetoed nine, or 82%.

“He came in on a reform platform which essentially was to hose out the Augean Stables,” said Martin Kaplan, associate dean of the USC Annenberg School for Communication, referring to the labors of Hercules. “And he ends up raising more money than Gray Davis, or anyone else, for that matter.”

Schwarzenegger has said repeatedly that legislators were “spending addicts.” But he has signed budgets that have raised state spending 27%, to $101.3 billion from $79.8 billion.

On a radio show, Schwarzenegger explained his ethics policy. Indian tribes that own casinos are “people that I would never take money from,” he said. That would be a “conflict of interest,” because a governor negotiates gambling compacts with tribes, he said.

Yet six tribes that own casinos have donated at least $800,000 altogether to the California Republican Party in the last two years. And the party has run television ads helpful to Schwarzenegger.

Schwarzenegger has a record of floating ideas and then dropping them. He vowed in 2004 to bust the Legislature down to part-time status. Never did it.

He told the Sacramento Press Club in January that he would set up a bipartisan commission to examine the state’s costly pension system. Never happened.

Then there are moments when he seems to simply get carried away.

Frustrated that lawmakers wouldn’t pass his budget, he appeared at a rally at a shopping mall in Ontario two years ago to ratchet up pressure. His staff had written a speech for him, but Schwarzenegger ad-libbed.

Before a crowd of more than 1,000 supporters, he called his legislative opponents “girlie men.” The audience loved it, but Democratic lawmakers were furious. The tone had been set for the next year, which Schwarzenegger had optimistically dubbed “the year of reform.”

*

Some of Schwarzenegger’s top aides never wanted the special election. After a flurry of campaigns in 2003-04, they thought he needed a year to govern quietly and squirrel away some money for a reelection bid.

But Schwarzenegger worried that if he didn’t go to the ballot with a dramatic proposal to shake things up, he might be facing years of paralysis in Sacramento, aides said. A big, bold step was needed, he believed.

Things came to a head at a meeting at a Sheraton hotel near the Capitol late in 2004. Schwarzenegger snapped at his staff that they had dithered, failing to prepare for the special election he envisioned.

One advisor recalls Schwarzenegger saying that without a special election, he “would be facing 18 months where nothing would get done.” He wouldn’t be talked out of it.

Schwarzenegger backed four measures that his allies placed on the November 2005 ballot: He wanted to curb state spending, revamp the way the state draws voting districts, make it tougher for teachers to get tenure and bar unions from making campaign contributions without permission from members.

The agenda wasn’t even his own. It had been cobbled together by the Chamber of Commerce, anti-tax forces and conservative leaders on the fringes of the governor’s political circle.

The program also was reminiscent of a Schwarzenegger mentor -- former Republican Gov. Pete Wilson. In the 1990s, Wilson went to the ballot to expand the governor’s budget-cutting powers and impose restrictions on union political activity. Voters said no.

The Republican operatives surrounding Schwarzenegger remembered those fights from the Wilson years. But maybe they’d have better luck with a former movie star as the salesman.

Joel Fox was co-chairman of a campaign committee that became the prime fundraising vehicle for the Schwarzenegger-backed initiatives.

In Schwarzenegger, he saw a “Mr. Olympia who has the ability to lift the weight of the world -- and we were going to jump on his back. That’s the attitude we had,” he said.

But “it didn’t serve Arnold well,” Fox said. “And I take part of the blame for this debacle.”

Teachers, nurses and firefighters mobilized against the governor’s agenda, picketing Schwarzenegger’s fundraising events from Manhattan to Los Angeles. Schwarzenegger could not muster grass-roots support or raise enough money to combat the union attacks.

“We stumbled around,” said Mike Murphy, the governor’s chief political strategist at the time. “We tried to do three years of reform in about six months.”

Battered by the unions’ TV ads, Schwarzenegger saw his approval ratings plummet. When defeat came last November, he moved quickly to recapture voters’ trust.

He had spent much of 2005 declaring he’d been sent to Sacramento to “fix a broken system.” Now he understood that voters wanted him to work within that system, broken or not.

A shake-up followed.

Murphy left to focus more on Hollywood projects. Shriver, injecting herself in the personnel search, as she often does when her husband is in trouble, found a replacement in Steve Schmidt, a barrel-chested veteran of the Bush White House who runs a no-nonsense political operation.

Out went Clarey, once an aide to former Republican Gov. Pete Wilson. In came Susan Kennedy, once an aide to former Democratic Gov. Gray Davis.

“That was his apology,” Kaplan said. “By hiring her, and taking pretty intense public criticism for it from his Republican base, he was saying: ‘I really heard you. I got it.’ ”

Embracing the Democratic agenda, Schwarzenegger signed bills raising the minimum wage and providing prescription drug discounts. It was effective politics, executed on the cusp of a reelection campaign.

But it also showed some flexibility: Schwarzenegger had tried something. It didn’t work. So he tried something else.

“He’s been a very reliable partner in advancing a very strong Democratic agenda,” said Fabian Nunez, the Democratic speaker of the Assembly. “It’s the ultimate irony.”

When something works, Schwarzenegger stays with it, his friends say. Now that his political recovery has put a second term within his grasp, he’s unlikely to risk another effort to shake Sacramento to its core.

“I’ve known him 27 years and I’ve never seen him happier than he is now,” said Bonnie Reiss, a longtime friend and a senior aide.

Others sound a more wistful note. They hoped Schwarzenegger would prove a transformational figure.

Right after taking office, Schwarzenegger embarked on one of the most ambitious projects of his governorship. Acting on his vow to “blow up the boxes” of government, he appointed 275 state employees, aides and consultants to plan how to do it. The group came up with a far-reaching program to wipe out 100 state boards and commissions. But when interest groups complained, Schwarzenegger backed down. The panel’s 2,500-page report, released more than two years ago, sits on bookshelves across the capital, ignored.

“I would like to have blown up a box or two,” Fox said.

Times staff writer Dan Morain contributed to this report.

For exclusive Web features, including the new Political Muscle blog, go to latimes.com/calpolitics.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

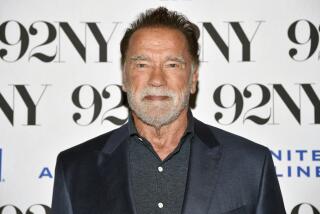

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Party: Republican

Occupation: Governor of California

Age: 59; born in Thal, Austria.

Residence: Los Angeles (Brentwood)

Personal: Wife, Maria Shriver; four children.

Education: Bachelor’s degree in business and international economics, University of Wisconsin-Superior, 1979

Career highlights: As a bodybuilder, won 13 championship titles; was the subject of “Pumping Iron,” a 1977 documentary about bodybuilding, and went on to star in many films; in 1990, was named chairman of the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports under President George H. W. Bush; sponsored Proposition 49, a ballot measure approved in 2002 to increase funding for after-school programs.

Platform: Job creation through economic development and promotion of the California economy; no tax increases; curbs on greenhouse gases through regulation of business; $37 billion in bonds to rebuild state infrastructure.

Los Angeles Times

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.