A Life of Payouts, Not Handouts

SANTA YNEZ, Calif. -- Growing up on the reservation, Kenneth Kahn waited in line with his mother for brick cheese, powdered milk and other government surplus food. He does not have a college degree or a paying job.

Yet at 27, he has accumulated more wealth than many working Americans will see in a lifetime. Every month, Kahn receives a check for nearly $30,000 -- his share of profits from the Chumash Casino Resort.

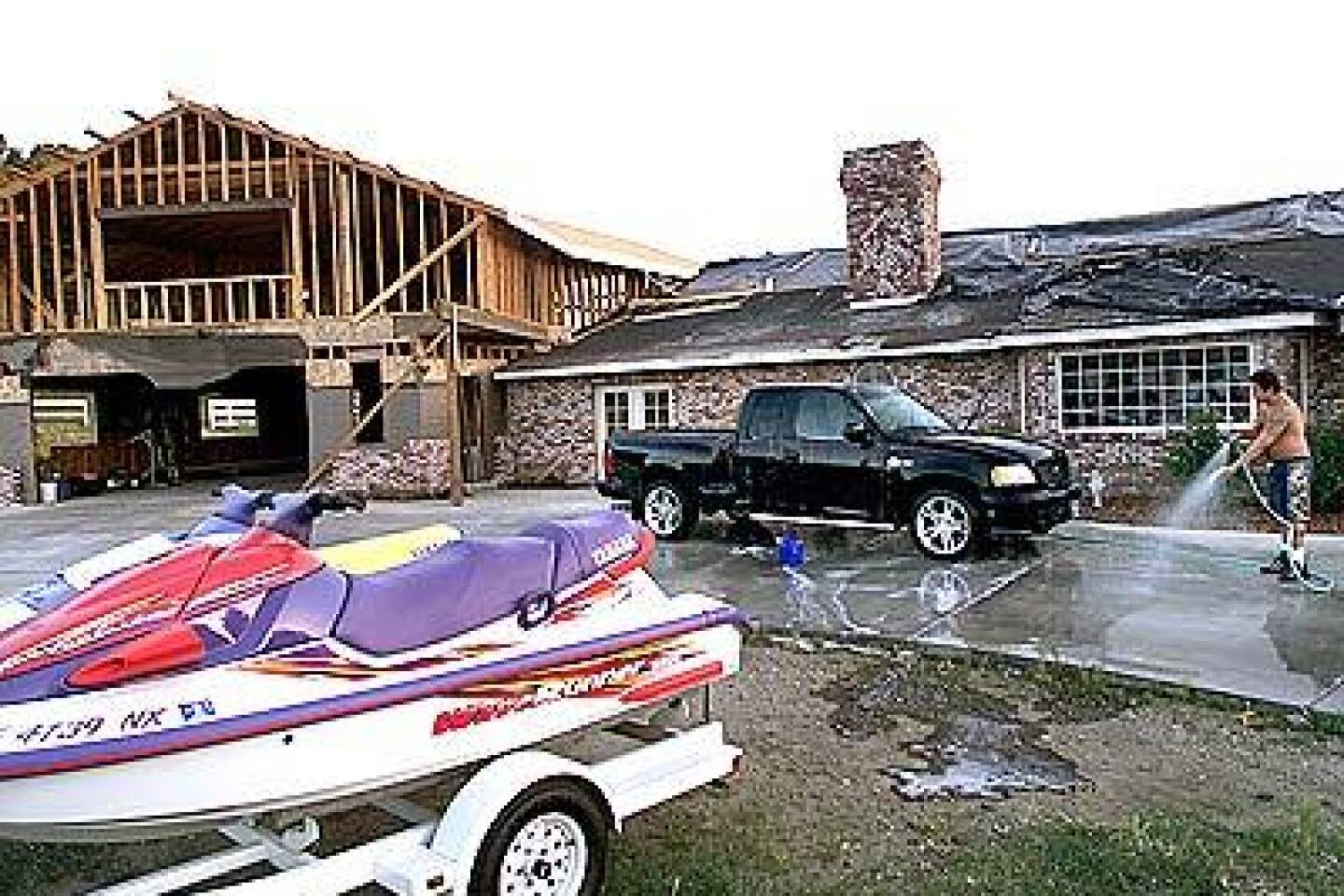

Scattered in his yard on the reservation here are a silver Range Rover, two oversized pickup trucks, a high-powered speedboat and a pair of all-terrain vehicles. He owns a vacation home in Lake Tahoe and recently paid $1.6 million for a five-acre estate in Santa Ynez.

“People ask me if I think I deserve it,” says Kahn, his shiny, dark hair neatly bundled in a ponytail.

“Not more than my ancestors,” is his standard reply. “I don’t care how many casinos we build,” he says. “We could never overcome what was taken from our ancestors.”

For much of the past two centuries, the Chumash of Santa Ynez lived in anonymity and abject poverty. As recently as the 1960s, reservation homes lacked running water, electricity and phone service. A decade ago, some Chumash still relied on welfare and donated clothing.

Then came the casino.

Since 2000, when California voters granted Native American tribes the exclusive right to offer Las Vegas-style gambling, each of the 153 members of the Santa Ynez band has received more than $1 million in casino income.

The torrent of money has caused a jarring transformation in the life of the Chumash. It has provided financial security and a bounty of material goods. It has enabled the Chumash to revive their language and instruct their children in the tribe’s ancient traditions.

But the sudden riches also have sparked conflict and fevered spending. Some tribal leaders worry that the monthly casino check is simply a new form of dependency, as corrosive as the welfare payments of old.

In the decades before gambling, many Chumash Indians toiled as ranch hands, truckers, maids and farmworkers. Now, they hire day laborers to tend their own sprawling estates.

They play golf at country clubs and vacation in Paris, Madrid and Maui. So many tribal members own vacation property in the Sierra Nevada that they jokingly call the area “Chumash North.”

Members who once subsisted on rice and beans enjoy gourmet meals and expensive bottles of champagne at their own upscale restaurant, the Willows. Women who once wore hand-me-downs and turquoise beads wear precious jewels and have cosmetic surgery.

“We’re not standing in line anymore to get cheese,” says Julio Carrillo, 60, a member of the tribe. “It’s like the American dream.... We got ours.”

Gambling proceeds pay for free medical care at a modern Chumash clinic and subsidize private schooling, tutors and college tuition.

And a people who had been relegated to the margins of history are reclaiming their identity. A decade ago, the tribe -- formally the Santa Ynez Band of Mission Indians -- had been largely assimilated into the local Latino community. Many were ashamed to acknowledge their Native American ancestry.

Now, casino earnings are underwriting efforts to build a Chumash museum, scour European collections for Chumash artifacts and revive the Chumash Inezeno language.

Powerless for so long, the Chumash are asserting their sovereign rights with new vigor, aided by lawyers, lobbyists and consultants.

“Given the way we were raised, we could never have imagined what we have today,” says tribal chairman Vincent Armenta.

Yet the costs of newfound wealth are as striking as the luxury cars that ply reservation streets and the private pools that dot backyards.

Some of the Chumash have run through their riches, spending themselves back into debt. So many people have gotten overextended that the band has withheld money from members’ monthly checks to pay overdue car loans and taxes.

The casino money has ignited bruising internal battles over ancestry. Some tribal members are challenging the bloodlines of their fellow Chumash, contending that they lack the one-fourth Indian blood required for enrollment in the band.

The money has also added to the bitterness of marital breakups. With legal support from the band, several Chumash Indians have fought to prevent former spouses from collecting casino money as part of divorce settlements, arguing that the tribe, as a sovereign nation, is exempt from California’s community property laws.

But the Chumash don’t dwell on the downside of instant wealth.

Kenneth Kahn, for one, sees only progress. Growing up, he was barely aware of the world beyond the reservation. Going away to college never occurred to him.

“My mom worked two jobs. I never saw her,” Kahn says. “If I had any direction, it would have been a different deal.”

Today, Kahn makes sure his 7-year-old son, Austin, has opportunities he didn’t. The boy attends a private Christian academy, is assisted by a tutor and attends after-school and summer programs -- all made possible by the casino.

Last year, Kahn was elected to the five-member business council that runs the tribal government. “I’m not proud of getting money for doing nothing,” he says. “I want to do the best I can to earn it.”

He is taking classes in political science and communications at Santa Barbara Community College and is thinking of pursuing a four-year degree.

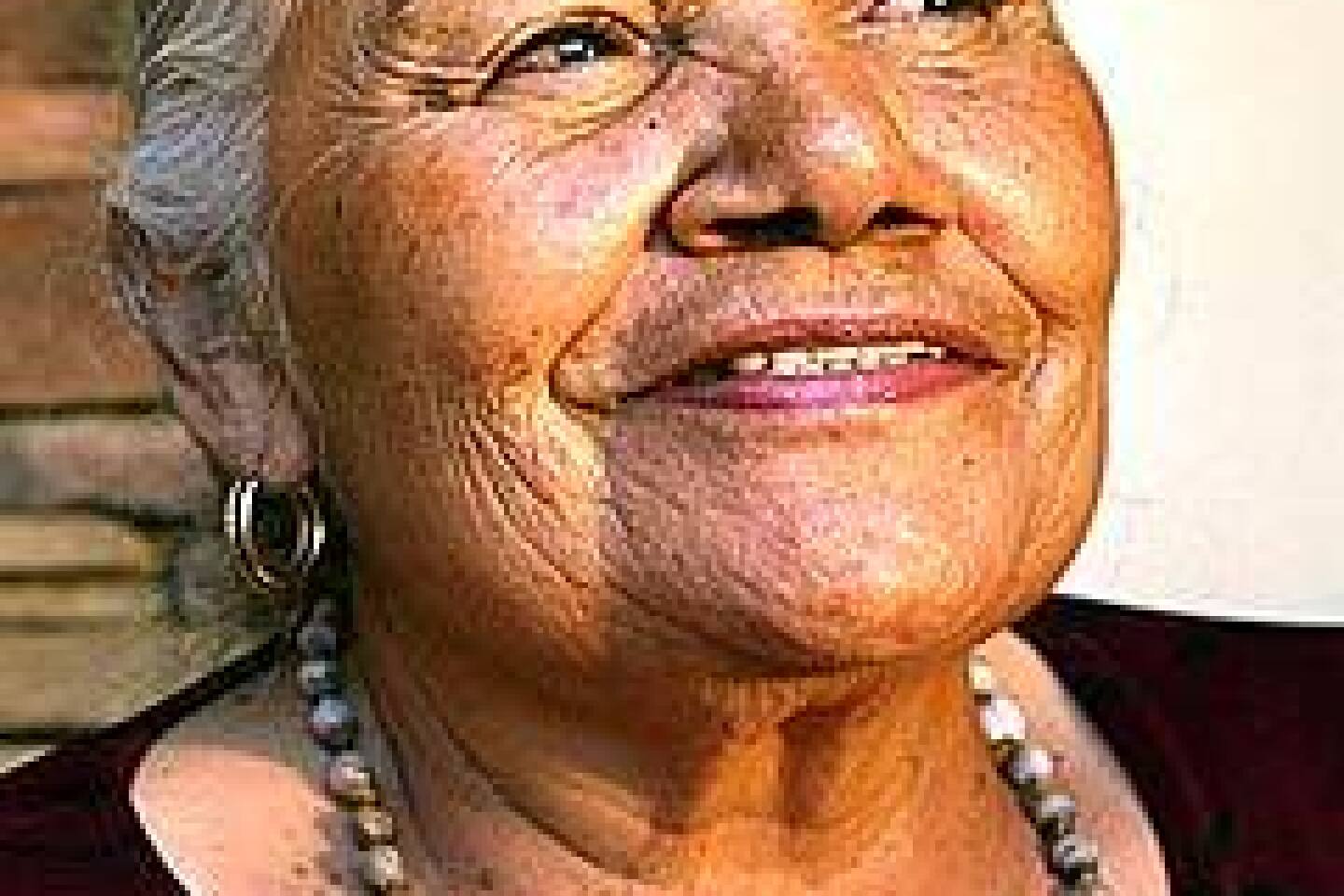

Years ago, Kahn’s grandmother, Rosa Pace, led the effort to bring drinking water, medical care and other basic services to the reservation.

Yet Pace, now 75, feels a deep ambivalence about the wealth generated by the casino. She is among a group of Chumash elders who call themselves “guilty Jag owners.”

Pace still washes dishes by hand and only recently yielded to relatives’ demands that she have a garbage disposal installed.

“It’s difficult,” she sighed. “I do feel guilty.”

Ancient Tradition

Historians say that Chumash Indians have maintained a continuous presence in Southern California for at least 5,000 years.

The earliest recorded sighting by a European was in October 1542, when Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo encountered Indians in wood-plank canoes along the Santa Barbara and Ventura County coastline.

The Chumash were expert hunters and fishermen who produced stone cookware and intricate basketry. Chumash society was hierarchical, with chieftains and shaman priests at the top of the pecking order and craftsmen and laborers at the bottom. Distinct Chumash dialects were spoken in each of dozens of villages.

The population began to diminish in the early 19th century with the establishment of five mission-based communities in Chumash territory, according to John R. Johnson, curator of anthropology at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

A 1798 survey counted about 1,200 Chumash in 14 villages in the Santa Ynez Valley. In 1804, Old Mission Santa Ines was built. By 1856, the number of Chumash in the valley had dropped to 109 -- a 90% decline caused largely by measles, smallpox and other diseases introduced from Europe.

A small cemetery next to the mission cathedral holds the remains of about 1,700 Indians, marked by crumbled tombstones and splintered crosses covered in moss. One small headstone reads simply: “Baby.”

During the late 1800s, the Catholic Church relocated the Chumash in Santa Ynez to Zanja de Cota Ranch, a 99-acre flood plain. The church eventually donated the land to the Indians, and in 1906, the U.S. government created the nation’s only federally recognized Chumash reservation.

This would become the tribe’s salvation, giving the Santa Ynez band a sovereign territory on which to operate a casino. But at the time, there was no hint of such a windfall.

Life on the reservation was harsh. The Chumash lived in dilapidated adobe dwellings. Rosa Pace remembers the sight of families climbing into trees from rickety rooftops to escape the floodwaters of Zanja de Cota Creek. Alcohol abuse was rampant.

“Santa Ynez was a frontier town,” says Johnson, who has studied the Chumash for three decades. “Some of the Indians developed into pretty rough customers. A couple of them ended up in San Quentin. But they persisted. They were people who made the best of what they had.”

The Armenta clan embodies the tribe’s impoverished past and its perseverance. Loreto and Florencia Armenta raised 10 children on the reservation during the Depression. The family lived in a lean-to without walls or windows and slept on steel cots lined up on a dirt floor. They bathed in a swimming hole and wore clothes made from discarded flour sacks.

“We didn’t have anything,” says Eva Pagaling, 80, one of the family’s four surviving children.

Over the years, tribal members married into Mexican and Filipino families and grew detached from the reservation. Many left to work on the region’s farms, picking fruits and vegetables.

In the early 1900s, the federal government began a decades-long practice of shipping Indian children to Catholic boarding schools.

“There was a movement to get Indian children away from their cultural awareness and teach them the West way,” says Jim Fletcher, regional superintendent of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. “In the 1930s, the perspective was: ‘How do we get them above the poverty line, get them an education and build them up.’ ”

Pagaling remembers the look of fear in her mother’s eyes when federal agents showed up on the reservation. “Mother told us to go hide in the willows,” she says. “She was afraid they would take us away.”

Eventually, Pagaling and two sisters were sent to Saint Boniface School in Riverside County. Every morning at 6, the Native American boarding students were required to line up wearing oversized military boots, Pagaling recalled. Their chores included scrubbing toilets and mopping floors.

She and her sisters returned to the reservation after a year. Like many of their generation, they were unaware of their Chumash lineage.

“We thought we were poor Mexicans,” she says.

Hitting the Jackpot

For many years, a rustic campground on the reservation provided the tribe’s only source of steady revenue. The Chumash closed the site in the 1970s because it failed to generate enough money to cover the cost of utilities and water.

The band turned to gambling in 1983. A high-stakes bingo parlor attracted gamblers from as far as the San Francisco Bay Area and provided part-time employment for dozens of Indians.

“The days of begging for water are over,” proclaimed then-tribal chairman Edward Olivas.

But the bingo hall closed in 1988 because of rising debts and a business dispute with outside investors. It reopened in 1990 in partnership with entertainer Wayne Newton, only to fold five months later, $250,000 in debt.

The band’s run of bad luck ended in 1994. Following the lead of other Southern California tribes, the Chumash began offering slot-machine games, despite warnings from law enforcement authorities that the devices were illegal.

The casino’s first general manager, Michael Lombardi, recalled gazing at a collapsed ceiling in the middle of the old bingo hall during his initial meeting with then-tribal chairman David Dominguez.

Outside, Chumash families huddled in the cold, waiting to receive surplus food from a tractor-trailer known as “the commodity truck.”

“I want there to be a day when that truck no longer comes to my reservation,” Lombardi recalled Dominguez telling him.

The band borrowed $600,000 to renovate the bingo facility and purchase 210 slot machines. Tribal members worked on the casino floor, provided security, directed parking and cooked burritos and fry bread for patrons.

Within three months, the band had paid off all of its start-up loans and installed 350 additional machines. The casino produced $31 million in revenue during its first year.

“When we put slot machines in that made $300 a day, everybody was in shock,” Lombardi said.

Even more remarkable were the profit margins. By 2000, the tribe was collecting $70 million a year in revenue -- and keeping 69% as profit, according to internal reports.

That same year, California tribes spent $24 million promoting a ballot initiative to legalize the reservation casinos and allow Indians to offer Las Vegas-style games of chance.

Proposition 1A passed, and casino revenue continued to soar. The Chumash spent $157 million on a new, Mediterranean-style gambling complex, which opened last year. The Chumash Casino Resort has 2,000 slot machines, a 106-room luxury hotel and an auditorium where Jay Leno, Fleetwood Mac and Whoopi Goldberg have performed.

The tribe recorded its first $1-million day in July, and casino revenue is expected to surpass $200 million this year -- a 40% increase from 2003.

The Chumash band allocates about 15% of its share of casino profits to the tribal government and various services and benefits. The remaining 85% is distributed directly to the 153 tribal members.

Only “enrolled members” of the Santa Ynez band -- people who have one-quarter Chumash blood -- are eligible for these monthly payments. Because Chumash frequently marry outside the tribe, most households have just one enrolled member.

Thousands of Chumash Indians outside Santa Ynez get no share of the riches because their separate tribes lack federal recognition. This is a source of bitter resentment in the broader Chumash nation.

“They’ve turned their backs on us,” said Al-lu-koy Lotah, a Chumash medicine woman and leader of the 80-member Southern Owl clan.

The Santa Ynez tribal government has used gambling proceeds to repave roads, erect street lights and build a sewage treatment plant. It has also acquired adjacent property, expanding the reservation by 49 acres to accommodate future development. Within the next decade, Chumash leaders hope to build a school, a day care center, a health club and a bank.

They are also investing in higher education. Now, there are just four college graduates among the band’s members. But in recent years, tribal subsidies have helped nearly 100 Chumash attend a university, community college or trade school.

Last year, the band achieved two “firsts” when one Chumash descendant enrolled in Stanford University and another graduated from law school -- at the University of San Diego.

Like many Chumash elders, Eva Pagaling could never have hoped to leave Santa Ynez for college. She worked for many years on an assembly line, packing frozen broccoli into food cartons.

Pagaling still lives on the reservation, in the modest, stucco house she and her late husband bought in 1979. She still remembers the excitement of moving into the home, her first to have electrical outlets and natural gas.

As she ticked off the improvements in her life since the casino opened, Pagaling also spoke of the disorientation brought on by so much wealth.

She maintains her bearings, in part, by clinging to old habits. Pagaling still buys $6 shirts at thrift shops and discount stores. “I love Wal-Mart,” she says. “I don’t care if I have money or not. I want to be the way I always was.”

Pagaling keeps putting off plans to buy a four-wheel drive sport utility vehicle to make the trip to her Lake Tahoe vacation home. She confesses to lingering regrets about the thousands of dollars she spent on a flat-screen television.

“I’m used to being poor and not having enough,” she says. “I know I can afford things. But for me, to spend that money.... It’s difficult.”

Fast Spending

When gambling revenue began to flow in the mid-1990s, there was widespread fear that the casino would not last long; law enforcement officials had repeatedly threatened to shut it down.

“They spent the money as fast as they could,” said Lombardi, the former casino manager. “They figured the gravy train was going to end.”

Many members had never used banks and continued to store their money in tin cans and in glove compartments of abandoned vehicles. Today, most have bank accounts. But the impulse to spend quickly persists.

“A lot of these people lived a very primitive lifestyle,” says financial advisor Stephen Drake, who has counseled tribal members on their finances. “They are going on a lot of trips and buying nice, very fancy cars. That, I believe, is human nature.”

Tribal members privately acknowledge that some Chumash have gotten in over their heads, despite their robust casino income. In several cases, the band has garnished a member’s share of gambling revenue to pay off debts.

Among those in financial distress is Gilbert Cash, the chairman of the tribal gaming commission who oversees gambling at the casino.

Cash, 38, has filed for personal bankruptcy twice in the past two years, piling up $128,502 in debts, including $60,000 in unpaid income taxes, according to court records. Cash says he fell behind because he wasn’t prepared to be thrust into a higher tax bracket. Members who reside on the reservation pay only federal income taxes.

Battles over casino wealth have complicated marital breakups. Two years ago, the band decreed that tribal income, by “custom and tradition,” is for the benefit of members only.

At the time, several Chumash members, including tribal chairman Vincent Armenta’s sister, Maria Feeley, were embroiled in divorces.

Chumash attorneys have argued in court that Tribal Resolution 852 takes precedence over California’s community property law. “We do not want the money to go to spousal support for nonmembers,” attorney Lawrence Stidham said during a recent divorce proceeding.

Stidham said that all tribes “struggle ... to protect and preserve” casino profits for Native Americans who have long endured unemployment and poverty.

In August, a state appellate court ruled against the tribe in the Feeley case, clearing the way for her ex-husband, Randy Jacobsen, to collect $3,500 a month in alimony.

“When you think about it, it is astounding what the tribe is trying to get away with,” said Vanessa Kirker, Jacobsen’s attorney.

Other tribal members have succeeded in denying spouses a cut of gambling profits.

Lewis Gray said has fought unsuccessfully for several years to compel his estranged wife, Cheryl, to make monthly support payments.

Gray, 45, who is not a member of the tribe, said Cheryl walked out on him several years ago, leaving him to provide for eight of their children, ages 6 to 17. He quit his job as a construction foreman, Gray said, to become a stay-at-home father in Fontana. He said he has run up $40,000 in credit card debt.

Last year, a judge ordered Cheryl to pay $12,166 a month in child support and alimony. Her family has made sporadic, partial payments. But the tribe has refused requests from child-welfare officials to withhold the full amount from her casino checks, according to Gray and his attorney.

“My lawyer says we can’t do anything about it because they are a sovereign nation,” Gray says. “This is not fair to me and my kids. It’s not right.”

At a June divorce hearing involving Manuel Armenta, a brother of the tribal chairman, Stidham was asked how ex-spouses could support themselves if casino money was off-limits. The Chumash lawyer replied that they could throw themselves on the mercy of the tribe.

“I wouldn’t put myself in the position of being humiliated,” Armenta’s wife, Zita, said in an interview. “That tribe would not do anything for me.”

A Life of Comforts

Dominica Valencia raised her three children in a one-bedroom shack near the reservation. She ran her own doughnut shop in the mornings and worked as a housekeeper in the afternoons. For years, her husband, Michael, also held two jobs -- as a welder and as a heavy equipment operator.

The Valencias no longer have to work. They donate their time to Native American programs, including the reservation clinic, pow-wows and a talking circle for Indian inmates at Lompoc’s federal penitentiary.

They also enjoy their newfound affluence. They own three homes and vacation in Hawaii every year. Once a week, they cook ribs on the backyard barbecue for their three dogs.

Yet along with the comforts have come unexpected complications.

The Valencias rarely entertain guests at home because the conversation often gets around to their casino riches. They were distressed several years ago to open their mailbox and find that the envelope containing the monthly check had been opened -- apparently by someone unable to contain his curiosity.

“It always comes back to the money,” Dominica says. “I get tired of that.”

She and her husband worry about the effect of wealth on young people. The Valencias said they were floored one afternoon when their teenage son asked: “Where is my share?” They say they sat him down and explained that he is not entitled to an extravagant lifestyle just because he is Chumash.

Dominica, 44, a member of the tribe’s education committee, is concerned that Chumash youths are growing accustomed to waiting for the casino check, just as their parents stood in line for surplus food.

“Some are going to college and building for the future,” she says. “Then there are those who have no drive or ambition.... We’re trying to tell kids there is more out there. Don’t be content with just getting money.”

Times researchers Maloy Moore and Penny Love contributed to this article. Glenn F. Bunting can be reached at glenn.bunting@latimes.com.

Return to the fold:

The experiences of three influential members of the tribe reflect the difficult times once faced by the Chumash, on and off the reservation.

Adelina Alva-Padilla

Adelina Alva-Padilla married at 16 and had seven children in as many years. A single mother, she raised her family in the Watts area, serving Quaker Oats for dinner, washing clothes by hand and rarely giving a thought to her Chumash origins.

Then in 1981, she moved back to the reservation, heeding her mother’s deathbed request. Like other city dwellers, she was not welcomed. “They told me to get the hell out,” she recalls.

Today, at 68, she is the spiritual leader of the tribe. Her one-story house is a sacred place where the Chumash pray, chant, mourn, dance and sing. She treats the sick with burning sage, condor feathers and hot sweats.

When the casino checks began flowing a decade ago, she bought her husband a house in his native Mexico. But she has eschewed most other indulgences. In her living room, Alva-Padilla keeps photos of two schoolteachers in Mexico with artificial legs and an impoverished South African man who is pursuing his dream of attending trade school.

“This,” she says, “is what I do with my money.”

Grace Romero Pacheco

Grace Romero Pacheco dropped out of high school after a year and worked menial jobs -- housekeeping at a motel, trimming seafood in a fish factory. She went on and off of welfare while raising seven children.

Not until the late 1950s did she learn about her Chumash ancestry. She moved onto the reservation in 1979. Once a month, she stood in line to collect rations of peanut butter, canned carrots and other government surplus food.

“It came in handy,” she says. “I was thankful for it.”

Now 71, Pacheco is a pillar of the reservation community. A former member of the tribe’s business committee and its gaming commission, she serves on the elders council and is learning the Chumash language.

She no longer needs food handouts. She enlarged her house to accommodate four generations of Romeros. A new Infiniti FX45 sport utility vehicle sits in the driveway. Two daughters and three grandchildren work at the Chumash Casino.

“I want a better life for my grandchildren,” Pacheco says. “I want them to be proud of who they are.”

Vincent Armenta

Vincent Armenta was raised on his parents’ walnut and lima bean ranch in Lompoc. In 1979, the family moved into one of the first government- subsidized homes on the reservation.

After high school, Armenta moved to Compton and worked as a welder.

He returned to Santa Ynez a decade ago and was elected tribal chairman in 1999.

He is one of 45 members of the Armenta clan who belong to the tribe. Altogether, they collect about $16 million a year in gambling proceeds.

Armenta’s 20-year-old son is a blackjack dealer at the Chumash Casino Resort. His 15-year-old son spent the summer as a bellhop in the resort’s new hotel. “They need to learn the value of work,” he says. “I had to do it when I was younger, and they have to.”

Armenta, 41, doesn’t radiate wealth. He wears jeans, running shoes and rumpled golf shirts, washes his own car, and says money hasn’t changed him.

“I’m the same person today I was 20 years ago. I have the same friends. I eat the same vegetables. I haven’t changed at all.”

*

About this report: This is one in a series of occasional stories on the impact of casino gambling at the Chumash reservation in Santa Barbara County.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.