Who Killed Sandy Bird?

Two decades ago, on a warm summer night, the wife of a minister and mother of three died under heartbreaking circumstances. Her station wagon ran off a gravel country road and overturned in the Cottonwood River outside Emporia, Kansas. Early Sunday morning hikers came upon the body, floating in shallow water.

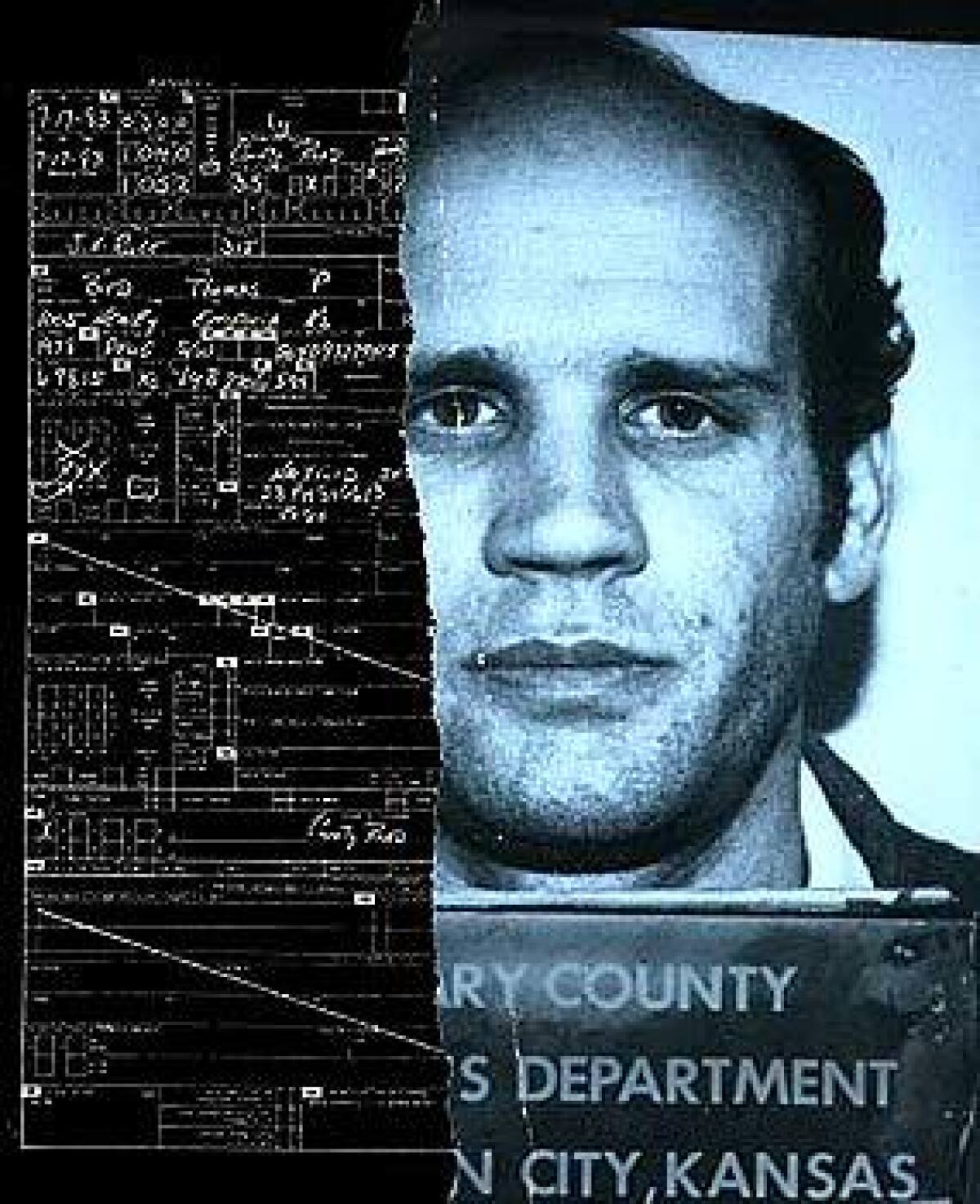

But the death of Sandy Bird wasn’t an accident. During the next two years, residents of that tranquil Midwest town watched an absorbing gothic tale unfold—a tale of adultery and religion, of murder and money. It ended with the first-degree murder conviction of her husband, the Rev. Tom Bird.

FOR THE RECORD:The article “Who Killed Sandy Bird?” (May 2) about the murder of a preacher’s wife in Kansas 21 years ago implied that she died “the night of July 17, 1983.” In fact, her body was found the morning of July 17.

Bird has fought unsuccessfully for a new trial. Serving a life sentence, he has a record as an exemplary inmate, but he was turned down for parole in 2001, partly because, the board said, “he denies responsibility for the crime.”

I wrote about the case for the Los Angeles Times in 1986. When my article appeared on the front page, it generated a buzz in Hollywood. By 1987, the case of the homicidal Kansas preacher was a two-part CBS miniseries, “Murder Ordained,” which survives today on cable.

Not long ago, the Rev. Kenneth Kothe, a friend of Bird’s from their days at a Lutheran seminary, sent me an e-mail from his home in Burnsville, Minn. Kothe argued that the movie, and its regular reruns, was helping keep the prison door closed, and unfairly. He urged me to take another look at the case, “given that yours was the article that triggered the making of ‘Murder Ordained.’ ”

At first, I was unmoved. It’s not exactly rare for a felon, or a defrocked preacher, to proclaim his innocence.

On the other hand, I wondered why Bird still refused to accept responsibility, especially when it might help him win parole. The case against him had seemed strong but I remembered it also being largely circumstantial. Was it possible? Had an Emporia jury put an innocent man in jail for life? Had Hollywood’s dramatization kept him there?

So I wrote a letter to Inmate No. 41458, who has never done an interview with a reporter. He wrote back, agreeing to see me. On a Friday afternoon, I arrived at the Lansing Correctional Facility, a razor-wire-encircled stone compound sprawled on rolling grazing land in northeastern Kansas. Passing through a metal detector and two heavy iron gates, I entered a room teeming with inmates and their families. A balding man of 53 in jeans and a blue work shirt rose from a plastic chair, smiled and raised his hand.

Today, I hope to find out, once and for all, what happened the night of July 17, 1983.

Sandy and Tom Bird moved to Kansas from Arkansas in 1982. Bird’s assignment was to lead a congregation for the Lutheran Church, Missouri Synod. Bird, the 32-year-old son of a minister, had two master’s degrees in theology and abundant charisma and energy. Within a year, he had the church pulsing with activity—a new day-care center, softball and volleyball teams, and new families coming every Sunday.

Sandy was a small, high-energy 32-year-old with short brown hair. She also had a master’s degree, in mathematics, and she began teaching and working on a second degree in computer math at Emporia State University.

Her husband’s passion was sports. A distance runner in his college days, he still ran more than five miles a day. He also was a fierce competitor on the Optimist Club basketball team and the church softball team. That interest in sports was shared by Marty and Lorna Anderson, whom Tom Bird met at a softball game.

The Andersons had four young daughters and a troubled marriage; Lorna’s many affairs were a poorly guarded secret in town. A femme fatale with a soft voice, she seemed to have a way of getting men to do her bidding. She joked to friends about killing her husband and once asked an attorney to prepare divorce papers. When Bird hired her as a part-time secretary, she sought out his shoulder.

“I had a real problem, not feeling good about myself,” Lorna told me in an interview after the trials. “Tom was very supportive, very encouraging.” She also said that by the spring of 1983, she and the pastor were lovers. “He told me that I was not what he needed in a wife, but that he could make me into what he needed.”

The Birds’ marriage also was strained by the demands of two careers and three young children. Bird was frustrated by his wife’s job, her friends said. Sandy told a friend that she was afraid her husband “doesn’t love me anymore.”

During that summer, Sandy learned she was being promoted and would have extra classes to teach in the fall. She and Tom went out to a dinner and a movie to celebrate. They returned home that Saturday at 9:30 p.m., and Sandy ran inside to grab a bottle of Cold Duck from the refrigerator for herself and a bottle of whiskey for her husband. She told the baby sitter they’d be back by 10:30.

Sandy’s body was found the next morning, next to her Peugeot station wagon, beneath the wood-planked Rocky Ford Bridge. Lyon County authorities said she had missed a bend in the road and careened down an embankment into the river. The death, they said, was accidental.

Four months later, on a remote two-lane road in nearby Geary County, Marty Anderson was shot to death. Lorna Anderson told investigators she had felt ill so she stopped the family car and ran into a field to be sick, but lost her keys. So she called to her husband for help. As they searched in the dark, an assailant in a ski mask appeared and fired two shots at Anderson, killing him.

The Geary County sheriff was dubious. Just how did the killer know that the Andersons’ car would stop at that exact spot? Suspicions grew a few days later when a spokesman emerged for Lorna Anderson: Tom Bird

Emporia authorities soon uncovered an earlier, unsuccessful plot on Marty Anderson’s life. Lorna Anderson had paid a local building contractor $5,000 to kill her husband. Authorities said the money came from Bird, part of his wife’s insurance proceeds. Anderson and Bird were charged with criminal solicitation. The contractor testified at the trial that Bird said, “I’m a man of God and I’m going to kill Martin Anderson.” Bird denied it.

Both the contractor and his brother had had affairs with Lorna Anderson, witnesses said. But it was the widowed preacher’s relationship with Anderson that drew suspicion. Witnesses described an ‘’electricity’’ between the two and said they had pet names for each other. Investigators found two cards from Bird in Lorna’s bedroom. “I love you and I’m confident of the future and that makes the present OK,” he wrote, signing one card: “Love you always, Tom.” Bird denied an affair, saying the cards showed “Christian love,” not “a romantic type of love.’’

Bird was convicted of solicitation; Lorna Anderson later pleaded guilty. (It would be five more years before Geary County gathered enough evidence to charge Tom Bird and Lorna Anderson with murdering Marty Anderson.)

With the solicitation conviction, pressure built to reexamine Sandy Bird’s death. Her body was exhumed in 1984 and examined by Dr. William Eckert, a forensic pathologist, who concluded that she had been struck on the head with a blunt object and died from a blow to the back, probably when she fell from the bridge into the river. A year-and-a-half after Sandy Bird’s death, a grand jury charged Tom Bird with killing his wife.

What really happened after the Birds left the baby sitter that night? Bird told police that they had a drink at his church office and then parted—she drove to her office at the university and he stayed to go over the next day’s sermon. He expected her to pick him up later.

The police received several calls from Bird before midnight, reporting his wife missing. But the baby sitter said Bird called home after midnight to ask if his wife had telephoned.

“Why would you look all over town before you checked with the baby-sitter to see if she was at home?” Lyon County prosecutor Rodney Symmonds later asked at the trial.

Also, Bird told police that after his wife dropped him off at the church, he went jogging, which he often did as a way of pondering the next day’s sermon. The baby sitter remembered, though, that he came home in a shirt and tie. Why had he changed back into his clothes? The prosecutor suggested that Bird had jogged the seven miles from the bridge and that his jogging clothes were probably covered with dirt and blood.

Another piece of circumstantial evidence was the testimony of the sheriff’s officer who delivered the bad news to Tom Bird the next morning. Bird’s reply puzzled him. “What was she doing out there? We never go there,” the officer recalled Bird saying. Only then did Bird ask: “Where is it?” The state had no eyewitnesses. It presented no physical evidence putting Bird at the scene. But it had the baby sitter’s memory of the time Bird called home and the officer’s memory of Bird’s comments the next morning. It also had a community polarized by the crime. Tom Bird was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

The case had drawn little attention outside the state, until Eckert, whom I had interviewed on other stories, called in 1986 to tell me about it. One of my first interviews was with John Rule, the Highway Patrol trooper who discovered the body. He was a shy 37-year-old, with a wife and small children, and we met one evening at his home. What he said surprised me: He had voiced suspicions about the accident from the first day.

“I started feeling hinky about the whole thing,” Rule said, when he couldn’t find any skid marks or signs of an attempt by the driver to stop.

Then Rule found Sandy’s watch under the bridge, and he spotted drops of blood on the bridge and on tree leaves below. “I thought something had happened on that bridge,” he said. But as the sun rose, the evidence was fast disappearing. Workers were trampling through the river bottom, removing the body and the car. Rule raised his concerns with the sheriff, who brushed him off, asking: Who would kill a preacher’s wife?

“There was a mountain of evidence down there if you had been working a homicide,” Rule said. “I was sure she didn’t die in a traffic wreck. But I didn’t have the training to prove otherwise.”

He was troubled that the driver’s seat in the car was pushed well back—too far for Sandy Bird, who was 5-foot-1, to have been driving. In addition, her friends said she always wore a seatbelt, yet she apparently had been ejected from the car. A test for alcohol showed she was sober.

“I kept thinking, ‘What was she doing out there alone after dark?’ ” Rule recalled. He sat up nights, feeling guilty that he had botched the investigation and angry that he couldn’t get the sheriff or the Kansas Bureau of Investigation to share his doubts. “It was so damn gruesome, so incredible,” he said. “You’ve got a minister’s wife, a mother of young children. Nobody wanted to believe it was a homicide. Hell, I didn’t want to believe it myself.”

My story opened with Rule and his doubts. The day the article appeared, several dozen producers began placing calls to Kansas. In the end, only CBS made a TV movie. Directed by Mike Robe, it featured Keith Carradine as Rule. Terry Kinney was a spooky, ethereal Tom Bird and JoBeth Williams played Lorna Anderson as his spellbound lover.

The film opens with Rule: “I’m feeling downright hinky about this,” he says. Bird emerges as the minister who falls for his sultry secretary, becomes unhinged and plots two murders. Given a choice between killing their spouses or divorcing them, he tells Lorna, murder is “the lesser of two evils.”

The dramatization was filmed almost entirely in Emporia, where the state’s governor even had a walk-on role. Some Emporians worried that Robe was taking too many liberties with the story. But the Emporia Gazette editorial page concluded that Robe “was faithful to the important part of the story and ... has nothing to apologize for.”

Emporia is a town of 25,000 resting on the doorstep of the Flint Hills, an unspoiled stretch of treeless plains in east-central Kansas. It hasn’t changed much since my visit nearly two decades earlier. Faith Lutheran, Bird’s former church, still welcomes Sunday worshipers in a quiet, modest neighborhood. But a few miles outside of town, the crime scene is no longer called Rocky Ford Bridge. These days, even the police call it “Bird Bridge.”

“This county believes in justice,” says Gwendolynn Larson, who covers police and courts for the Emporia Gazette newspaper. “Whether they got it is a question. Some people think they didn’t; some think they did.”

After driving two hours north to Lansing, home of the state prison, I have dinner with several of Bird’s defenders. Kothe and Dave Racer, whom Kothe hired to write a book on the case, came down from Minnesota. Also joining us is Terry Bird, who married Tom in a prison ceremony in 1988.

Kothe, 58, knew both Tom and Sandy years ago. When Kothe saw “Murder Ordained,” he exchanged letters with Bird and began working to prove his innocence.

Racer, 56, wrote “Caged Bird,” a self-published book that argues Bird was convicted on flimsy circumstantial evidence in a town hell-bent for justice. “If you look at everything, each of the circumstances can be explained,” Racer says. “They had very little evidence.”

“If that movie had not been done,” Kothe adds, “Tom would be out of prison. The movie, I believe, keeps him there. They play that every year, sometimes twice a year. And it makes it difficult for anyone to have sympathy for Tom.”

Terry Bird is working at a Lutheran school in Kansas City, Kansas. A friendly woman with short blond hair, she has a master’s degree in education with a specialty in teaching children with learning disabilities. She met Bird at a church function shortly after his wife’s death.

“People say I must be crazy’’ to marry a convicted murderer, Terry says. “But I have been to every trial. I have both feet on the ground.”

Tom bird was a balding, smooth-faced man of 33 when he was arrested.After two decades in prison, he walks stiffly, the hair on the sides of his head has turned gray and his face has aged. With his blue eyes, he resembles the actor Robert Duvall.

“I don’t even know if I should be talking to you,” he says as we shake hands.

During our conversation that day, and again later on the telephone, we talk about Sandy, Lorna and his trials. He tells me about life behind bars and his failure to win parole. He seems philosophical. “The one thing prison teaches you is that you’re not indispensable. Terry’s life has gone on. She can take care of herself. My children’s lives have gone on.”

Bird acknowledges that he and Sandy were having marital troubles in 1983. He says he supported Sandy’s career, “but we had disagreements about how much time each of us was spending at our jobs. We spent all this time at work and then we had three kids under 5. We didn’t leave time for each other.” That’s what they were discussing the night Sandy died, he says.

As for the evidence against him, he says he put a polo shirt on after his run. “The baby sitter, bless her heart, was wrong about that. I was wearing a tie probably 15 of the 20 times she saw me, but not that night. Why would I change into a tie after running? It doesn’t make sense.”

Bird says the baby sitter also was wrong about the time that he called home to ask if Sandy had telephoned. The baby sitter had said Bird called at 1 a.m. Campus and city police records indicated Bird had called them earlier. Bird tells me he called police only after calling home. “The baby sitter was a good kid, but she was just 14. I think she may have fallen asleep and not known what time it was. After she told me no one had called, I called the campus police.”

Bird remembers well the deputy sheriff who delivered the news of his wife’s death. The deputy gave a general description of the accident location, four miles outside Emporia, and Bird says he and his wife had never been there. Then, he says, he asked where it was to more precisely pinpoint it, because he’d never been there.

The prosecution theory was that Sandy and Tom went to the river together, got out of the car and walked onto the bridge to talk. There, Tom beat her and forced her off the bridge. Bird then pushed the car from the road down into the river next to her.

Bird says he doesn’t know what happened to his wife. He thinks it’s possible she was depressed or careless, but he doubts she committed suicide. “I don’t know whether it was an accident or suicide or murder. All I know is that I didn’t kill Sandy.”

He admits that the facts don’t support an accident. Perhaps, he says, Lorna Anderson or one of her former boyfriends had something to do with it. But he doesn’t have any evidence. “I just have to think that if all the evidence had been collected properly that day, I wouldn’t have been charged.”

Bird’s relationship with Lorna Anderson underpinned both of his guilty verdicts. I ask him the nature of their relationship—lovers or friends?

“She was emotionally attached to me,” Bird says. “And, on my end, there was a need to be needed. I liked the idea of being needed, so I unprofessionally let that happen. It was more emotional than physical.”

A few months after he wrote the notes to Lorna, in early 1984 after both of their spouses died—and not before, as Lorna claimed—they did become lovers, Bird says. They were intimate “three or four times,” before his arrest in March 1984.

In “Murder Ordained,” Bird persuades his lover that it is less evil to kill than to divorce their spouses. That was what Lorna Anderson had told me for my original article. But Bird calls that notion “preposterous” and “laughable.” “I never thought such a thing. She typed notes from my lectures and I discussed the ‘lesser of two evils’ view. But I taught against that. It’s an abomination in my mind that that is presented as one of the prosecution’s theories.”

He believes the movie helps keep him in prison. “It seems like it is shown every time there is movement in my case,” he says. “I believe it has an effect on the people making decisions. They’re confronted with the television version, and I imagine that’s pretty hard to get out of their heads.”

By all accounts, Bird has been a model inmate. He co-founded Convicts for Christ. He organized a tennis marathon to raise money for Ronald McDonald House. And he and Terry started a marriage enrichment seminar in 1988 for inmates and their spouses.

That made him a strong candidate for parole when he became eligible in 2001 after serving 15 years. During a lengthy parole hearing, Bird says, board members thanked him for his work in prison. They asked him whether he thought Sandy’s death was an accident, suicide or murder. “I said I didn’t think it was suicide, but I thought there was just as much evidence it was a suicide as there was that I murdered Sandy.”

Public hearings drew emotional pleas from Bird’s detractors, who include Sandy Bird’s relatives, and his supporters, including his eldest daughter, Andrea Bird, now 25 and working for a mortgage company in Orange, California. “I’ve stood by my dad the whole time,” she says. “When I was in junior high, I decided for myself that he was innocent. It was a lot of circumstantial evidence and he should have had a change of venue. The press convicted him there in Emporia.”

After the parole hearings, rumors swept the prison that he would be released. Bird got his hopes up. But the board decided to leave him in prison at least four more years, citing the serious nature of the crime, the objections from the victim’s family and his refusal to take responsibility for the crime.

“I was pretty devastated,” Bird recalls. “If that’s the reason they passed me over, then in four years there will be continued objections, the nature of the crime will still be serious and I still will be saying I’m innocent. I can’t take responsibility for what I’ve been convicted of. I took my wife’s life for granted, but I didn’t take her life. I can’t take responsibility for the crime.

“Freedom is a state of mind,” he continues. “When I’m locked up in here, my freedom has been taken away. But a more important freedom is freedom from the condemnation of your own conscience. I couldn’t leave here and know that I lied just to be free from prison.”

The kansas parole board was, in fact, deeply divided. It was impressed by Bird’s prison work but troubled by his claim of innocence. In the board’s view, admitting guilt is an important step toward proving that an inmate is ready for release.

Marilyn Scafe, the parole board chairwoman, tells me that in two decades on the board, she has never seen a case that so polarized the members. Scafe voted in favor of parole and three members voted against.

Hollywood’s version of the case was a complicating factor. When crimes are made into movies, “it makes it real confusing,” Scafe says. “When they retell the story, factual or not, people who are familiar with it the first time around get validated for their feelings, and it has the power to convince other people that these are the facts.”

As for the board itself, the members discussed “Murder Ordained,” but “as we looked at all of the facts we had from different documents, the movie faded.” By the time they began deliberating, “we were basically looking at the facts.”

The conundrum was Bird himself. “When someone maintains his innocence, that’s where we really have a hard time. We can’t, and we don’t, try to retry the case.” Still, she says, “there wasn’t a lot of physical evidence. And I just didn’t see him as someone who was capable of doing that. Of course, we get conned every single day. That’s the dilemma.”

Regardless of his guilt, Scafe feels Bird has served enough time. But, she adds: “I’m glad I wasn’t sitting on the jury.”

I ask Robe, who directed the movie, whether he has second thoughts. “Our movie was a fair presentation of what happened,’’ he says from his office in Burbank.

“I don’t think there’s a movie or a newspaper article that keeps Tom Bird in jail. I think it’s his own actions. I give the audience more credit than that. And the members of the parole board watching ‘Murder Ordained’ today aren’t going to be persuaded one way or the other by a film created for television. Docudrama is one thing. Adjudicated, real human and legal events are another.”

I track Trooper Rule down by telephone. After the movie, some people in Emporia were angry with him, so he had requested a transfer to western Kansas. “I’d stop people and, when they saw my name, they didn’t want to talk about speeding. So, I just decided to start fresh. As long as I was in Emporia, I was going to keep stirring the pot up.”

He’s 57 now, and he retired from the patrol after 29 years of working Kansas traffic accidents. Every time the movie airs, Rule says, “I get letters from all over the world.”

Rule has read Racer’s book, “Caged Bird,” “cover to cover, and before I was done, I was totally convinced he did everything he was accused of, plus maybe a little more.”

In the end, it is Tom Bird’s word against a case built on an incomplete investigation, the testimony of a 14-year-old baby sitter, Bird’s lack of an alibi and his relationship with Lorna Anderson.

Did Lorna Anderson or one of her friends in Emporia have a hand in Sandy’s death, as Bird’s supporters suspect? There’s no hard evidence of that, though Anderson had no shortage of other male friends in town. But the trial focused on Bird’s relationship with Lorna, and that was enough motive for the jury.

It seems clear that getting a fair trial back then in Emporia would have been difficult. Everyone had an opinion. Ray Call, the Gazette’s editor at the time, told me that the trial had the town drowning in “a bottomless reservoir of gossip.”

Guilty or innocent, Bird faced an uphill battle for release once convicted. My article and Robe’s movie certainly haven’t helped. But it’s hard to believe that they keep him in jail. Bird’s refusal to cop to the crime, a principled stand if he’s truly innocent, has probably been more responsible for keeping him behind bars.

And then there is this: A few years after the movie, in 1990, Bird went on trial for first-degree murder in the death of Marty Anderson. Lorna Anderson pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in exchange for her testimony against Bird. She said she and Bird had planned the killing together—and that Bird was the masked man who gunned down her husband.

She had first made that claim to me, in 1986, and I had mentioned it in my original story. After an appeal from the prosecutors and Marty Anderson’s brother, the Times agreed to allow me to appear in the second murder trial, to testify that my story’s account of Lorna Anderson’s remarks was accurate. The prosecutor had been worried about her credibility, he told me privately, “inasmuch as Lorna has told so many stories.”

His concern was justified. Bird was acquitted and no one else has been charged in Marty Anderson’s death.

Lorna Anderson, now serving a sentence of 15 years to life, has come before the parole board several times, and each time has been turned down. The decisions haven’t been close. “We got a lot of information on her,” she says, citing “some confidential issues” and declining to elaborate. Looking back, I am reminded of what one of the investigators had told me about Anderson: “A lot of what she says is true. Some is not. And there’s a whole lot she’s not telling.”

As I finish reexamining Bird’s case, the board decides to reopen his file early and consider placing him in a work-release program. After public hearings in April, the board plans to see Bird again this month. He will be facing a different body. The board now has just three members, one of whom is new and believes the case is worth considering. Another member who voted to deny Bird parole feels he has served enough time. And Scafe, the third vote, says, “I never wanted to pass him [deny him] in the first place.”

“But I want sunshine on it,” Scafe says. “I don’t want anyone to say we’re doing something behind the victim’s family’s back.” If the board puts Bird in a work-release program, she says, “we’re saying that unless you screw it up you’re going to get parole eventually.”

Soon, it seems, Tom Bird, still professing his innocence after 20 years in a Kansas prison, will be free.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.