Beyond the Trappings

It’s hard to be an absolutist in the modern world—our society simply isn’t set up for it. Boundless, diverse and brimming with energy, it’s better at fostering a culture where anything goes than one obsessed with strict definitions of right and wrong. It’s better at building a spiritual world where people customize their beliefs rather than demanding they adhere to rigid dogma. There is no black and white anymore. Most of us prefer our world in muddier-but-subtler, ever-evolving shades of gray.

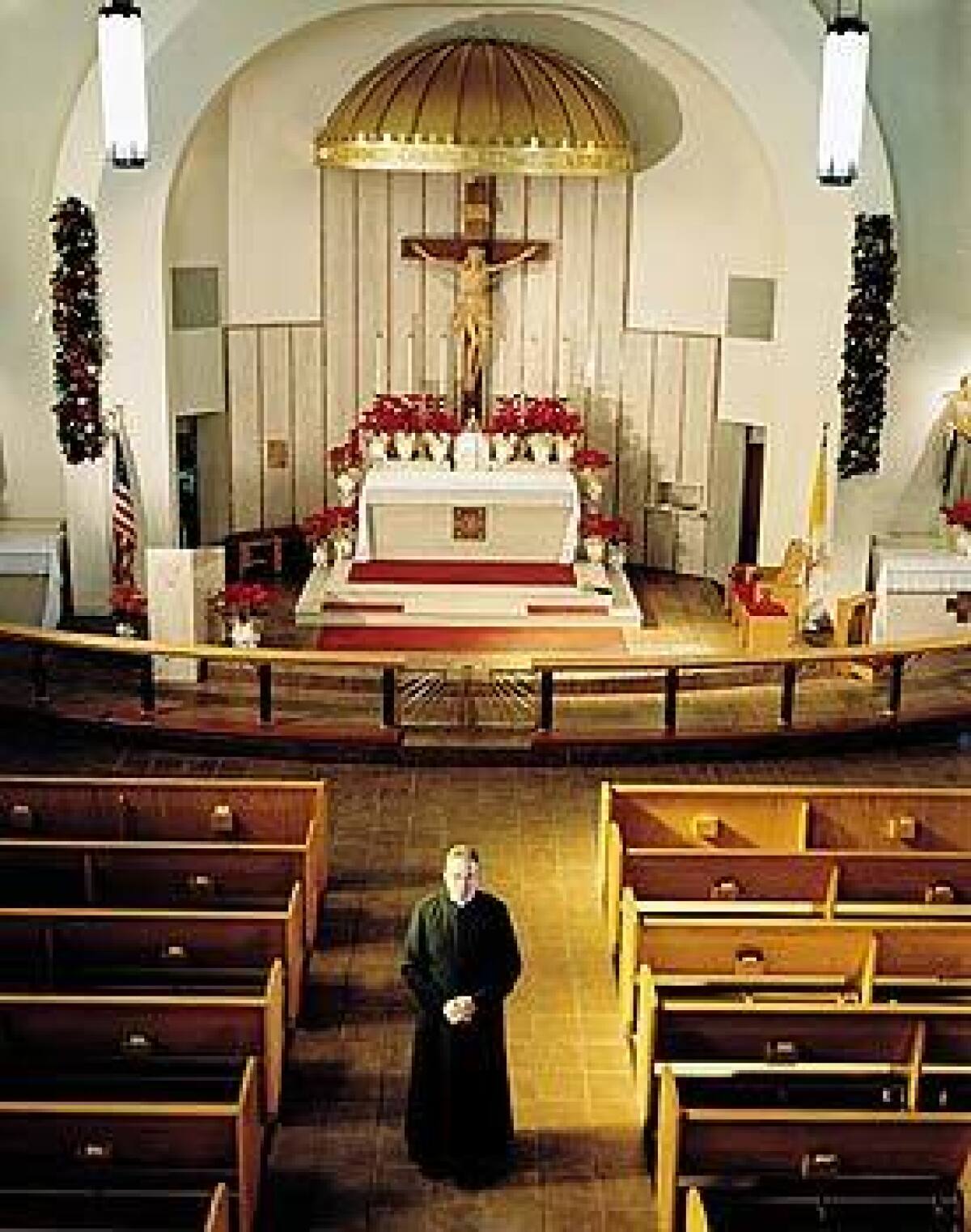

So there’s a certain otherworldly feeling you get when you walk into a tiny, plain church in the Santa Clarita Valley and sit down with a man of the cloth who’s certain that certainty does exist. He’s friendly and calm, and he explains his take on the world in a patient, soothing way—even as his words are unforgiving. “Just because we’re in different times,” he says, “it doesn’t mean that right and wrong—true and false—change. Today nothing is sacred. Everything is open to reinterpretation. But if something is handed down by Christ, it shouldn’t change.”

You might assume your host is a Protestant fundamentalist, cousin to those evangelicals who preach salvation on the cable channels that pop up between MTV and HBO. If you took out the reference to Christ, he could even be an orthodox rabbi, admonishing his followers to keep the Sabbath and to follow the many commandments of the Torah to the letter.

But this particular man of faith is Father Dominic Radecki, a youthful-looking, 46-year-old Catholic priest who wears a standard-issue clerical collar and black suit, who sits rather informally on a plastic chair he’s pulled up just a couple of feet away from yours, and who will later display an album stuffed with photos of the seminary he attended, as well as several of his scuba badges. It’s an odd combination of old and new, rigidity and informality. And it’s especially curious coming from a person you associate with Roman Catholicism—a religion that for the past 40 years has attempted to modernize, if not quickly enough for many of its devotees.

There is, of course, a catch: Father Radecki is not a mainstream Catholic—he’s what’s called a traditionalist. Traditionalists are devoted to the Latin Mass, and they have little but scorn for the modernizing innovations of Vatican II, the groundbreaking council called from 1962-65 by Pope John XXIII, who believed that the insular church needed to adapt in order to survive in a rapidly changing world. “I want to throw open the windows of the church so that we can see out and the people can see in,” the late pope said. Vatican II resulted in—among many other changes—the introduction of a new Mass, outreach to other Christian faiths and this statement: “What happened in [Christ’s] passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today.”

Since then, many traditionalists have not recognized the pope as their leader. And yes, they are strict fundamentalists. Traditionalists do not eat meat on Fridays. Their women wear skirts and cover their heads in church and are encouraged to stay home and instruct their children in the ways of upright living. In the traditionalists’ world, there is black and there is white; gray was merely the color of the sky on the day Jesus was tortured and crucified.

There aren’t a lot of traditionalists around—probably fewer than 100,000 in the U.S. And they might have retained their somewhat in-the-shadows identity had not the most famous adherent among them, Mel Gibson, decided to sink $25 million of his own money into a controversial feature film about the trial and punishment of Jesus—a film that has inspired accusations of anti-Semitism and inadvertently shined a klieg light on its director’s fellow travelers.

“The Passion of the Christ” opens on Feb. 25—Ash Wednesday. It has been seen by only selected audiences, as Gibson has tried to control early criticisms of the movie. The controversy surrounds the film’s depiction of Jews and the inclusion of a biblical passage that blames them for the death of Jesus, a line that reportedly was cut. Religious organizations, theologians and academics—Christian and Jewish alike—are distressed because the Roman Catholic Church has, since Vatican II, absolved Jews of Jesus’ crucifixion. There are fears that Gibson’s film will usher in a new era of anti-Semitism.

Depictions of Gibson’s spiritual life have tended toward the sensational. As he prepared to shoot “The Passion” in Italy, a newspaper there reported that Gibson said, “I do not believe in the Church as an institution,” and that he believes the Vatican is a “wolf in sheep’s clothing.” The independent chapel he has built near Malibu has been shrouded in secrecy.

Then there are the rather unsavory opinions held by his 85-year-old father, Hutton Gibson, whom the filmmaker has credited with providing “my love for religion.” According to a story that ran in the New York Times Magazine last March, the elder Gibson has written books declaring the pope “the Enemy,” and has claimed that the Al Qaeda hijackers had nothing to do with the events of Sept. 11. He also thinks that the Holocaust didn’t happen.

The thing is, all the fuss over the Gibsons can distort what Catholic traditionalism is about. Mel Gibson is Southern California’s only traditionalist star, but he isn’t Southern California’s only traditionalist. In some 20 or so chapels such as Radecki’s, spread out from San Diego to Santa Clarita, hundreds of faithful congregate for the Latin Masses on Sundays and send their kids to traditional Catholic schools during the week. They’re young and old, black and white, Latino and Asian, rich and poor. They are a fractious bunch—these are, after all, folks who have taken the radical step of breaking away from Rome—and they differ somewhat in their takes on the pope, the “conciliar church” (as they call mainstream Catholicism), and each other. At the same time, they’re united in their disdain for the new Mass and for what they perceive as a grievously liberal Catholic Church.

It can seem like an unforgiving way to live, a lifestyle completely unsuited to our times. But the funny thing is, when you talk it through with people such as Father Radecki, you start to understand where they’re coming from. Press accounts about Hutton Gibson notwithstanding, most traditionalists don’t seem to be conspiracy theorists, or kooks. They’re strict and rigid, but they’re not nuts or hostile. They’re just very traditional people who want to pray and live in a certain, just-so way. They find a way to make it work in the modern world.

“It’s not like I don’t believe in technology,” Father Radecki says, displaying pictures of the recording studio he once worked in, producing religious music.

On another day, a different traditionalist priest plainly states: “Just so you know, we’re not crazy people.”

Still, they have an unyielding belief that theirs is the one true church, their faith encourages women to have large families, and, according to one leader, “we can’t change history” regarding the role of Jews in the crucifixion of Christ.

It’s a typical Sunday morning at Our Lady of the Angels Church in Arcadia. Mass is scheduled to begin at 10 a.m., but by 9:45 the church’s parking lot is already full, and parishioners have stationed their cars down Temple City Boulevard and onto the adjacent residential streets. The men dress in coats and ties, the women in modest skirts. Those women who haven’t brought a hat or scarf take a small lacy veil from a rack just outside the sanctuary door and place it atop their heads. Even the youngest girls wear head coverings—little pink knit hats, little pink muslin kerchiefs.

There are lots of small kids at Our Lady of the Angels, which reflects the strict traditionalist ban against birth control. (During a recent service, the priest told his flock that a large family might cause financial pressure, but “faith will provide.”) Some families show up with four or five children in tow. The kids sit quietly through the 90-minute service, only fidgeting occasionally. It’s a remarkable sight. Church and synagogue can be hard to sit through under any circumstances, for adults as well as for youngsters. But Our Lady of the Angels does regular boring church one better.

Following the old Tridentine rites, Father Charles Ward performs the service entirely in Latin—except for the biblical readings and his sermon, which is lengthy and didactic, focuses intensely on Scripture and offers advice and guidance for good Catholic parents. The line for Communion is long. The choir sings for some time, too. And yet, throughout, the children sit quietly and behave, every hair in place.

Our Lady of the Angels is one of three chapels in the Los Angeles area run by the Society of St. Pius X, a worldwide traditionalist organization that was banished from the Roman Catholic Church in 1988 when its founder, the Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, was excommunicated by Pope John Paul II. Lefebvre, who operated near Sion, Switzerland, had been battling it out with the popes and their cardinals ever since the close of the Vatican II Council in 1965. Even as the Latin Tridentine Mass was phased out, and eventually banished from use, Lefebvre stubbornly kept performing it.

The society also trained and ordained dozens of traditionalist priests, monks and nuns, and built seminaries, monasteries, schools and churches around the world. Lefebvre got his walking papers, so to speak, after he consecrated four bishops without first obtaining permission from the pope. Today, despite its turbulent history vis-à-vis relations with Rome, the Society of St. Pius X is considered a centrist group among traditionalists. “They’re the moderates of the movement,” says Michael Cuneo, a professor of sociology at Fordham University in New York City.

One recent afternoon, sitting in his basement office at Our Lady of the Angels, Father Ward explains the group’s beliefs. Ward is a Chicago native, and he wears wire-rimmed glasses and a black cassock with a black cardigan sweater. He seems mild-mannered enough—until he starts to talk and an edge begins to show through. Ward sought out the Society of St. Pius X after a brief stint as a student in a mainstream seminary, back in the late ‘70s. “God gave me the grace to recognize the problems in the church,” he says. “I saw from the inside what was going on. I went in to the seminary, and it was as bad as college. It was a circus. There was homosexuality. There was drinking. People were in each other’s rooms. Pictures of scantily clad girls were on the walls. Seminarians don’t have bars in their rooms, and they don’t go to bars at night. After being scandalized, I found Lefebvre.”

As Ward sees it, depravity in the church stems primarily from losing the “sacrifice of the Mass,” as he puts it—from the decision of the Roman Catholic Church to get rid of the Latin Mass and create the Novus Ordo (Latin for “New Order”) liturgy. “When you destroy the life of prayer, you destroy the life of belief,” Ward says. “And that’s what they did.”

Ward pulls out a set of Pius X pamphlets, their covers printed in bright colors and tabloid headline-style print:

“Who Are We? What Are We Doing?” “Why the Traditional Latin Mass? Why NOT the New?” “Where is Catholic Obedience Today? Not Where You Might Think,” and so on. Their argument? That the traditional Catholic Mass was first and foremost a sacrificial rite, but that Vatican II turned it into a “meal.” Where once there had been an altar in the church, now there was a table. Where once a priest communicated for his congregants, now he performed. Where once the Mass had been a way to salvation, now it was mere entertainment.

The pamphlets—and Father Ward—blame the changes on ecumenism, the tenet of Vatican II that holds that all religions have merit. Ward tells me that the church adjusted the liturgy “to accommodate Protestants,” and points accusingly at one of the brochures, toward a photograph of six Protestant ministers who he says advised the Vatican II council. It’s a photo that other traditionalist priests will show me as well.

This kind of talk led to Lefebvre’s break with Rome. But the Society of St. Pius X has not rejected John Paul II’s position as the legitimate head of the Catholic Church—as many traditional groups, called sedevacantists, after the Latin for “the seat is empty,” have. Still, it takes some interesting logic to embrace the pope and simultaneously reject his church.

Father Ward keeps a portrait of Pope John Paul II hanging on the wall above his desk. In the portrait, the pope is turned, hands outstretched, toward the spot where Ward sits. When Ward turns and gestures toward the picture, it almost looks as if the two men are blessing one another.

“We say we are the best friends of the pope,” Ward explains, looking up at the Holy Father. “We are defending the traditions of the church—and that’s his job. Are we obedient? We are obedient to all of the popes. Not just this pope, but all popes. And if this pope is in contradiction to all the other popes, we have to obey the old popes. Follow the logic. What is obedience? If a parent tells a child to steal, a child can’t obey. That would be excessive obedience. There are higher laws. Virtue stands in the middle.”

Ward looks back down from the portrait. “We accept that he’s the pope. We just think he’s weak. That’s sad. But it’s nothing new.”

There are, of course, other groups of traditionalists besides the Society of St. Pius X—and this is where the picture gets confusing. One of the better-known of these groups, the Society of St. Pius V, broke away from Archbishop Lefebvre in 1983 over the issue of papal legitimacy. There aren’t any St. Pius V chapels in the Los Angeles area.

Several churches, however, are part of a third traditionalist group, Mount St. Michael, or Congregation of Mary Immaculate Queen (CMRI), which is based in Spokane, Wash. Father Radecki, who heads Queen of Angels Church in Newhall, explains that the congregation parts ways with the St. Pius X society when it comes to the legitimacy of the popes since Vatican II.

Other traditionalist chapels in the region are independent. Mel Gibson formerly attended Our Lady of the Angels, but decided to establish an unaffiliated chapel, reportedly because the church in Arcadia was turned over to the Society of St. Pius X. The Archangel Gabriel Chapel in Glendale is an “associate” of the Society of St. Pius X—primarily, Father Ward says, because its pastor, Father Joseph Melito, does follow the pope. At the same time, the chapel is hardly within the fold of the mainstream church. Before they are allowed inside, newcomers who attend Sunday Mass in its converted warehouse space must sign a release affirming that they understand the chapel operates independently of the archdiocese.

Another independent operator, the St. Francis of Assisi Chapel in Van Nuys, takes another tack. While the congregation’s leader, Bishop Thom Sebastian, says he personally doesn’t recognize the legitimacy of the pope, he chooses not to talk about it from the pulpit.

But there is one commonality among all traditionalists: a strict devotion to the Bible, which includes Matthew’s account of Jesus’ condemnation by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate. A group of Jews who witnessed the event are supposed to have said, “His blood be on us and on our children.”

“We just hold to what the church has always held,” says Father John Fullerton, district supervisor for the 110 churches in the U.S. affiliated with the Society of St. Pius X. “The physical crucifixion was performed by the Romans, but it was the Jews who urged the Romans to do it, as the Bible says. The Jews were the ones who sought the crucifixion, so in a certain sense they’re responsible for it. They were the ones who condemned him, but they didn’t have the power to crucify him, so they got the Romans to do it.”

Consequently, traditionalists have no reason to accept the church’s absolution of Jews in Jesus’ death.

“We can’t change history,” says Father Fullerton, speaking from his office in Kansas City, Mo. “The things that are in line with tradition, we hold to, but if it goes away from history, we don’t hold to it.”

How does all of this translate to relationships with Jews that St. Pius X society members might have in everyday life, with neighbors and co-workers? Is there an official traditionalist position?

“There is no official position,” he says. “We want people to become Catholic. The Lord himself was a Jew. We have no animosity toward Jews. We want them to see the full truth. The Lord came to show them, but not everyone was willing to see it.”

Talking to members of Father Charles Ward’s church in Arcadia after Mass one Sunday, I get a more light-hearted take on what traditionalism is all about. Immediately after the service ends, I’m set upon by Javier Rodriguez, an eager 44-year-old parishioner who takes it upon himself to give me the dime tour of the church. Rodriguez grew up near downtown in a Latino community where, he says, “you still had a lot of tradition.” Unhappy with the changes he saw creep into the church in the 1970s and ‘80s, he started looking for a traditional alternative, and eventually found a service offered by Father Frederick Schell, who led a number of local Latin Masses until his death in 2002. Rodriguez joined Our Lady of the Angels in 1994, and has been a regular fixture at the church ever since. “The Society has stayed the same all along,” he says.

Rodriguez proudly walks me through the church bookstore, its shelves filled with books about the stigmatist Padre Pio and martyrs such as the virtuous rape-and-murder victim St. Maria Goretti, as well as missals in a multitude of languages. As we’re browsing, Rodriguez explains his take on John Paul II: “It’s like the emperor has no clothes. The people surrounding the emperor don’t tell him. Now a draft is coming, and he’s feeling the cold. But the Society has his beautiful garments—the Mass and the sacraments—and we’re asking him to put them on!”

Just outside the bookstore, congregants mill about for coffee and doughnuts. Models of the area missions, made by the church school’s 4th graders, are on display in the middle of the room. Father Ward sits nearby eating his lunch, a little squirt bottle labeled “Holy Water” on hand to bless parishioners who approach him.

Rodriguez catches sight of Diana and Eugene Duggan. The Duggans, 39 and 44 years old respectively, have eight children. For many years, they attended occasional Latin Masses performed by an independent priest. They turned to the Society of St. Pius X because they wanted their kids to experience parish life the way they had known it growing up, with a regular Latin Mass, school, social activities and so on.

Several years ago, Diana Duggan moved to Idaho so that their oldest sons could attend a St. Pius X school in Post Falls. Now they’ve moved back and the children attend Our Lady of the Angels, which opened its own school in 1997. “It’s a lot of commitment, but that’s what it’s all about,” Eugene Duggan says. “For the children, it’s important to have the total environment. And that’s where the conciliar church has fallen apart.”

The Duggans paint a picture of traditionalism that isn’t without its conflicts. The 47-student school at Our Lady of the Angels only goes through the 8th grade, so oldest son Miles, now 18, had to attend a regular Catholic high school (a “Catholic school in name,” as the Duggans put it), where many of the teachers and the other students didn’t share the Duggans’ commitment to their faith.

“The emphasis wasn’t on being Catholic,” Eugene Duggan says. “And if what we were teaching them about the prayers and devotions at home was different than what they were learning at school, it could be hard on the kids.”

At the same time, Duggan says he thinks it’s important that the kids be exposed to other kinds of people. “They have to deal with life,” he says. “We’re not trying to hide them.” Miles plans to attend Pasadena City College, where he will study to become an emergency medical technician.

But do traditionalists encourage the same path for girls? Their church teachings, after all, make it plain that a woman’s place is in the home.

“Most definitely, they go to college,” Diana Duggan says. “I think college is important, especially if you’re going to be a mother. So you can teach your kids.”

Diana, however, did not attend college. Before they had kids, she helped her husband start his own hair salon.

“My vocation is being a mother,” she says. “So [a career] is not really something I’m missing, because I’m not working in the world. My vocation is to mold these young children into something good. My only frustration is that maybe I’m not doing it well. I just trust that what may seem like a sacrifice to others is what God wants from me.”

Duggan says she hasn’t heard of people leaving the church because of the rigors of the lifestyle. She says many of her fellow parishioners had been attending the conciliar church and become disheartened. Still, to an outsider, it was startling to hear Father Ward’s recent sermon about the constricted roles for women.

“If we took a friend from outside in, maybe they’d be shocked,” Duggan says. “But anyone who chose this path would not be upset by what Father says.”

They’re churchy people, to be sure, and way more conservative than your average Angeleno. But the scene, all in all, is aggressively normal. No one seems to be on the outer fringes, the way Hutton Gibson is portrayed. (Father Ward, indeed, goes out of his way to tell me that his church “doesn’t espouse Mr. Gibson’s theories, whatever they are,” and that “if Mel Gibson’s father is a sedevacantist, we don’t condone it. He would not come to worship here.”) No one seems hostile or paranoid or resistant to talking to a reporter. Even when I mention that I’m not Catholic, no one seems to care.

Rodriguez, for his part, seems to have an easygoing attitude about it all. He’s a single man in a church that is all about large families, yet he seems to feel at home. He claims that following the strictures of his faith isn’t hard—”I’m just a Catholic,” he says. “I pray every day and get on with my life.” Rodriguez boasts at one point that monks were the ones who invented champagne and beer. He also goes on a bit about food, extolling the virtues of a trendy L.A. restaurant where you wouldn’t expect to find stern, apocalyptic types. “You know, we can’t eat red meat on Fridays,” he says happily at one point. “It’s not so hard, though. I was eating too much red meat anyway!”

Almost to a person, like the worshippers at Our Lady of the Angels, other area traditionalists cite personal reasons for seeking out the church. For some, it’s a matter of hurt feelings. George Porter, who attends Bishop Sebastian’s church in Van Nuys, tells a story of being yelled at by a priest who would not allow him to kneel for Communion, as he always had in the past.

For others, it’s a matter of aesthetics. Some in his flock, Father Radecki says, like coming to Queen of Angels because they see it as a place where they “can have quiet worship—an interaction between the person and God,” he says. “The Latin Mass is sublime and mysterious, and worshippers like that. It’s different. It’s peaceful. And it helps people face the rest of their busy week.”

Catholic traditionalists complain about the sinfulness of the world around them, and often bristle at the notion that any religion, other than their own, has merit. But mostly they resist the idea that change is part of their faith. Asked what she doesn’t like about the modern church, St. Francis of Assisi member Darlene Smith says, “Any change. When they moved the tabernacle. When they made open confessional. The main thing is, if God says do this, that’s what I have to do.” Traditionalist critiques of the modern church are often harsh, and pointed. During my meeting with Father Ward, for example, he pulls out a small book called the “Index of Leading Catholic Indicators,” written by a St. Louis-area attorney named Kenneth C. Jones (and with a laudatory blurb from Pat Buchanan displayed prominently on the back of the book jacket).

“The statistics [in the U.S.] are pretty shocking,” Father Ward says, flipping through the pages and reading aloud. “Between 1965 and 2002, the number of religious seminarians decreased by 95%. Religious seminaries, down 75%. A 33% decrease in diocesan seminaries,” he says. “You look at the graph here, and it’s like, Hello? There’s a problem here.”

One of the other problems Father Ward cites is the church’s sex abuse troubles, which he blames on an institution unwilling to face the consequences of its liberalization. “We don’t let homosexuals take vocations here,” he says.

Ward’s parishioners follow his lead concerning modernization, especially regarding the Latin Mass. The Vatican has responded to fondness for the old rituals by allowing a few priests to perform the Tridentine Mass in its churches. But many traditionalists dismiss these “indult” Masses, saying that they’re both incorrectly performed and too cut off from other aspects of church life.

Not surprisingly, none of this tension has done much for the traditionalists’ relations with the Roman Catholic Church. As far as Rome is concerned, these chapels aren’t Catholic at all. “There’s a question of what’s Catholic and what’s not,” says Tod Tamberg, a spokesman for the archdiocese. “Is the church that you’re in in union with the Holy Father in Rome? If it is, it’s Catholic. If it isn’t, it’s not.”

Tamberg scoffs at Ward’s notion that the church is in crisis. “The question of vocations in the church is certainly a serious issue. But facile answers from people who have separated themselves from the church are not the first place I’d look for answers to this question,” he says. “The archdiocese has 5 million Catholics. The church has a billion members worldwide. Seventeen percent of the world’s population is Catholic. The boat isn’t sinking.”

By and large, the traditionalist Catholics have been a fairly low-profile bunch who’ve attracted new members by word of mouth rather than through massive PR campaigns, or associations with the likes of celebrities such as Mel Gibson. However, with the release of “The Passion of the Christ” on 2,000 screens nationwide, it seems likely that some attention and interest could start flowing their way.

Not that any of them appear to be especially worried. When asked about the movie, most don’t even seem to consider the possibility that all the focus on Gibson might somehow reflect on them. Of all the people I interview, only Father Radecki volunteers any direct mention of the controversy around the film, which he has not seen. “It’s totally wrong to get the impression that it’s OK to persecute the Jews,” he says. “Christ didn’t believe that. The movie doesn’t stir up hatred for anyone. Just sorrow for our own sins, and regrets.”

Everyone else, pretty much, just seems excited that Jesus’ story is getting some airplay. “I find it interesting that this movie is bringing attention to traditional Catholics,” Bishop Sebastian says, “when it should bring attention to Jesus, who is who the movie is about. If Gibson were any other type of director, there would be no discussion. I think anything that portrays our Lord in a positive light is good. I hope it’s a good movie. I hope it shows people how much Jesus loved us. I hope it helps them convert themselves, and become holy.”

“It sounds like it will be a wake-up call,” Eugene Duggan thinks. “A wake-up call to Christianity.”

But overall, it doesn’t really matter to these traditionalists what happens with the movie. Whether it does well or fails, or draws attention to them or doesn’t, they’ll still be celebrating the Latin Mass, raising large families and otherwise living a conservative Catholic life. “Saving souls,” as they like to say.

“Hopefully there’ll be some good reactions to the movie,” Father Ward says. “That might possibly help tradition, yes. It may help people come back to the word that Christ made a sacrifice for us.”

In a recent sermon, Father Ward decried the film industry’s casual depictions of divorce and remarriage. He apparently did not recognize this irony: It is Gibson’s very success in that God-less industry that has allowed him to make a religious film no one else would.

On this one thing, both mainstream and traditionalist Catholics would have to agree: The Lord moves in mysterious ways.

Eryn Brown last wrote for the magazine about Southern California’s real estate boom.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.