Terror detainee to get nine months

- Share via

GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA — Detainee David Hicks will be home in Australia within two months and will be free before New Year’s Eve despite a decision Friday by the first U.S. war-crimes tribunal here that he should serve seven years in prison in his homeland.

Under a secret plea bargain, all but nine months of Hicks’ sentence on one count of providing material support for terrorism is to be suspended.

The 31-year-old Hicks, who has been imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay for more than five years, secured the reduced sentence by promising he would never allege he was mistreated in U.S. custody and would cooperate with prosecutors in any future civilian or military trials of other terrorism suspects.

The deal that rendered moot the sentence imposed by an eight-member military panel appeared likely to draw more criticism of the Pentagon’s detention and trial operations here, because it suggested political influence had been exerted on the case and because it exposed a potential flaw in the Military Commissions Act of 2006.

Commission rules prohibit the judge from telling the sentencing panel that an agreement exists that would preempt their decision.

Ten senior military officers were summoned to Guantanamo by the civilian convening authority, Susan J. Crawford, and flew in via Washington on Friday from posts around the globe to sentence Hicks.

Two of the 10 were dismissed: The prosecutor, Marine Lt. Col. Kevin Chenail, used a peremptory challenge against the only woman, an Air Force lieutenant colonel with a law degree; and the defense attorney, Marine Maj. Michael Mori, used a peremptory challenge against a Navy captain who indicated he got his news from the Fox News Channel.

The military judge, Marine Col. Ralph H. Kohlmann, told the commission members that a maximum sentence of seven years could be applied to this case in exchange for the guilty plea that Hicks entered Monday. The charge ordinarily could carry as much as a life sentence.

Chenail gave an impassioned closing statement casting Hicks as a dangerous Al Qaeda asset capable of blending into Western society and bent on killing Americans.

He invoked the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and the profound changes they had brought in urging the jurors to give Hicks the maximum of seven years.

Mori portrayed his client as a ninth-grade dropout who wanted to be a soldier and went abroad in pursuit of a misguided idea of armed service.

Hicks was no asset to the terrorists in Afghanistan, Mori said, but rather became scared, ran amok and abandoned his post.

The panel spent two hours deciding a sentence. Kohlmann thanked them for their service without informing them of the pretrial agreement.

Because the jurors traveled here on such short notice and returned the maximum sentence so swiftly, they might look askance at the convening authority’s consent to the much lighter sentence.

But none of them are allowed to speak to the media, commissions spokeswoman Army Maj. Beth Kubala said after the case concluded.

By court rules, they cannot be identified other than by rank and branch of service.

Hicks’ case was the first before the newly reconstituted trial forum, which replaces one deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court last year. His trial was set before all the rules and procedures had been worked out by congressional liaisons and the Pentagon, after Australian Prime Minister John Howard applied diplomatic pressure on the Bush administration to try Hicks or release him.

Howard’s Liberal Party has suffered from a perception among Australians that his government has done too little to rescue a countryman from more than five years of U.S. imprisonment.

Charges against Hicks were filed less than a week after Vice President Dick Cheney visited Australia and Howard, a key ally in the U.S.-led war on terrorism, made clear the Hicks case was hurting his party’s electoral chances.

Human rights advocates criticized the plea deal as perverting a judicial process.

“What we’ve seen is a rush to trial that gives the appearance that this is about politics, not justice,” said Jumana Musa of Amnesty International.

Jennifer Daskal of Human Rights Watch said the U.S. government’s main interest appeared to have been to enjoin Hicks from ever alleging he was mistreated in U.S. custody.

Under his agreement, Hicks is prohibited from speaking to the media for a year, he must give the Australian government any proceeds from books or other accounts of his experiences, and he may not bring legal action against any U.S. service member or citizen.

On Friday morning, before the commission members arrived from Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, Kohlmann accepted the plea Hicks entered Monday and pronounced him guilty of one element of a charge of providing material support for terrorism.

On each of 35 allegations, Hicks was asked whether he understood the accusation and agreed that the government probably could prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. He admitted to training at Al Qaeda camps, guarding a Taliban tank in Afghanistan, casing the empty U.S. Embassy in Kabul, the Afghan capital, and other acts in support of the designated terrorist organizations.

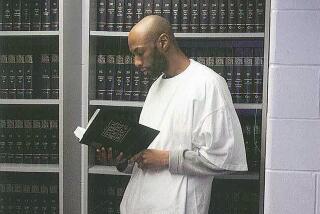

Hicks, who appeared in the courtroom Monday unshaven and with straggly chest-length hair, sported a neat new hairstyle Friday and wore a close-fitting gray suit. Kohlmann quizzed him on whether he was coerced into pleading guilty, and he answered politely and calmly that he was not.

The plea deal guarantees that Hicks will be transferred to Australian custody within 60 days of sentencing and probably much sooner, Mori told reporters after the terms were made public. Hicks is still designated an enemy combatant and will remain at his cell in the maximum-security Camp 6 until transfer, officials said.

The 35-point charge sheet presented to the commission members was a modification of the original indictment. All references to a connection with the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks were omitted, as were mention of Hicks discussing with Al Qaeda members his willingness to commit an act of martyrdom and his reported associations with notorious suspects including so-called American Taliban John Walker Lindh and Briton Richard Reid, the would-be “shoe bomber.”

The revised list of accusations suggested Hicks’ contacts with Al Qaeda were limited and low-level. An earlier clause accusing Hicks of having “expressed his approval” of the Sept. 11 attacks was changed to state that Hicks had no foreknowledge of the hijackings.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.