Antipsychotic Drugs of Limited Benefit in Alzheimer’s, Study Finds

Drugs widely prescribed to control agitation, aggression, hallucinations or delusions in Alzheimer’s patients provided few, if any, benefits and carried severe side effects, according to a large study released Wednesday.

The findings challenged conventional wisdom about the medications and painted a grim picture of the state of Alzheimer’s treatment.

“We need a new generation of drugs for these very serious behaviors,” said Dr. Thomas R. Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, which paid for the study. “These existing drugs are not the answer for most.”

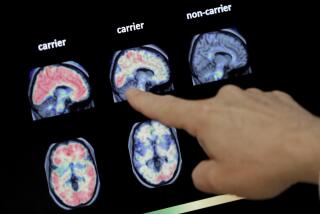

Alzheimer’s disease is a brain disorder that progressively impairs memory, thinking and behavior. An estimated 4.5 million Americans have the disease, most of them older than 65.

In the later stages of the illness, many experience severe personality changes and psychotic symptoms, posing major challenges to caregivers.

No drugs have been approved to treat these symptoms, but studies have suggested antipsychotic drugs developed for treating schizophrenia may help.

The drugs carry a “black box” warning -- the Food and Drug Administration’s strongest -- about an increased risk of death in Alzheimer’s patients.

The study set out to assess the effectiveness of antipsychotics Zyprexa by Eli Lilly & Co., Seroquel by AstraZeneca and Risperdal by Johnson & Johnson.

A total of 421 patients with moderate to severe psychotic symptoms, agitation or aggression were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo or one of the antipsychotics for up to 36 weeks. All patients lived at home or at an assisted-living facility.

The trial measured effectiveness by how long patients took a drug before quitting because they couldn’t tolerate side effects or saw no improvement. On average, patients stopped taking their pills after about eight weeks, about the same duration as those taking a placebo.

Depending on the drug, 37% to 50% of patients discontinued their pills because they weren’t working, and up to 24% stopped taking them because of side effects such as drowsiness, weight gain and confusion. All told, 82% of patients quit their drugs.

The findings, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, were unexpected, said lead author Lon Schneider of USC.

Despite the results, Schneider said the drugs had a role in treating some of the worst Alzheimer’s symptoms. The study hinted that some patients might benefit from the pills, he said.

“The message from this study cannot be that the drugs are not useful,” he said. But doctors should change or discontinue medications if patients have side effects or don’t improve in a matter of weeks, he said.

Dr. Claudia Kawas of UC Irvine, who was not involved in the study, predicted doctors would continue to use the drugs because there were no alternatives.

“The behavioral problems of Alzheimer’s disease are huge,” Kawas said. “To my mind, this study says these are powerful drugs and if given in high enough doses to do any good there are going to be side effects.”

An earlier trial, also federally funded, found the medications provided little benefit for schizophrenia patients and were no better than an older, less expensive drug, clozapine. That drug is not used to treat Alzheimer’s.

In the latest study, patients who discontinued their medication went on to a second phase of the $16.9-million study in which they received one of the drugs they hadn’t tried or the antidepressant Celexa. The results of that trial are being analyzed.

*