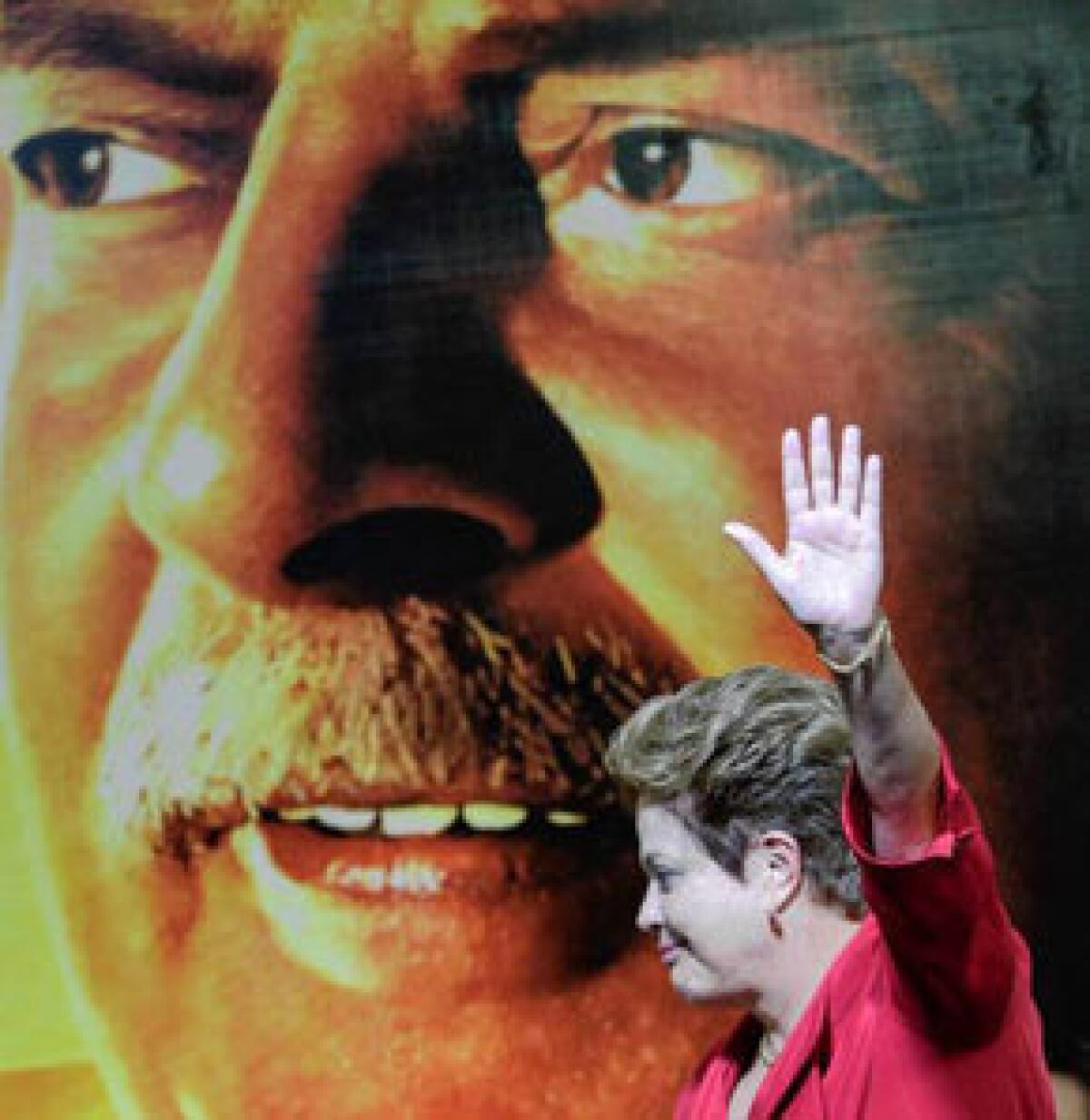

Brazil’s Dilma Rousseff is popular, but not among news media

SAO PAULO, Brazil — When left-leaning President Joao Goulart was deposed by the Brazilian military in 1964, the nation’s major news media, controlled by a few wealthy families, celebrated.

But during the 21-year dictatorship that followed, the government censored the newspapers and television stations the families operated.

Things are different now. Since 2003, Brazil has been run by the popular left-of-center Workers’ Party, known as PT, which has left the news media alone.

But the publications and TV stations, still controlled by the same families, have been critical of the party, despite a public approval rating for President Dilma Rousseff as high as 78%. Not a single major news outlet supports her, with some newspapers and magazines particularly harsh in their criticism.

“It’s an extremely unique situation now in Brazil to have such a popular government and no major media outlet that supports it or presents a left-of-center viewpoint,” says Laurindo Leal Filho, a media specialist at the University of Sao Paulo.

The opposition to the Workers’ Party has been present since former left-wing metalworker Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, once imprisoned by the dictatorship, was elected president in 2002. Lula quickly moved to the center and accommodated business elites, and the following decade saw an economic boom in which 40 million people rose out of poverty.

“Brazilian society was based on slavery for over 300 years, and has almost always been run by the same social strata,” Leal Filho says. “Some parts of the upper class have learned to live with other parts of society that were previously excluded … but the media still reflect the values of the old-school elite, with very, very few exceptions.”

The critical news media have been widely praised for hard-hitting investigations of corruption that have led eight members of Rousseff’s Cabinet to be replaced, and 25 high-level officials to be sentenced for a vote-buying scandal dating to Lula’s administration. But government supporters often say the news media pay much less attention to evidence of corruption involving other political parties.

Reporters Without Borders recently issued a report criticizing media concentration in Brazil and recommending an overhaul of laws pertaining to the media. But unlike elsewhere in Latin America where governments openly battle with private media critics, the Brazilian government has taken a relaxed attitude.

Even if there were a concerted effort to take action, it would be politically impossible, analysts say. The Reporters Without Borders report details close ties between parts of the media and members of Congress, some of whom even vote to grant licenses to outlets they own, especially outside the bigger cities. To run the country, Rousseff must navigate the complicated waters of the Brazilian congressional system and work with more than 20 other parties.

“It’s unfortunate, but to govern this country you have to establish alliances,” says Mino Carta, editor of Carta Capital, the only publication of any size that supports the government. It sells 60,000 copies a week in a country of almost 200 million.

Meanwhile, Rousseff, who was tortured by the dictatorship for her left-wing activities in the 1970s, has taken criticism from the news media in stride, periodically reaffirming her belief in freedom of speech.

Attempting to build a large-scale news outlet that presents a different point of view would be extremely difficult, Carta says, because of the need for advertising revenue.

“That would be a very slow and long-term goal indeed,” says the Italian-born septuagenarian.

Most Brazilian media chiefs say their journalism is neutral and objective.

Sergio Davila, managing editor of Folha de Sao Paulo, Brazil’s highest-circulation newspaper, says, “When Fernando Henrique Cardoso was in office, [his party] the PSDB said we were against them and pro-PT.”

Davila points to a report published in the paper at the time detailing votes purchased to ensure Cardoso’s reelection. “Now we’re just seeing the other side of the coin.”

But many PT supporters see the major newspapers, including Folha and O Estado de Sao Paulo, as anti-Rousseff, as they do the television network and newspaper run by the dominant Globo group.

“The big media have always defended powerful interests,” says Jose Everaldo da Silva, a retired port worker and PT voter in the country’s traditionally poor northeast, which has benefited especially from PT rule. “Everyone remembers what Globo did in Lula’s first election.”

When Lula first ran for president in 1989, the Globo TV station heavily edited his final debate with Fernando Collor de Mello, giving Lula less time and showing all of Collor’s best moments. The polls turned in favor of Collor, who was elected and later impeached for corruption.

The episode became the subject of a British documentary titled “Beyond Citizen Kane.”

Globo TV later acknowledged having made a mistake but denies there is now any bias. “Globo is absolutely nonpartisan. It doesn’t offer opinions on governments and seeks neutrality in its news programs,” a spokesman said.

TV stations are relatively moderate and a more important source of news than print for Brazilians, most of whom don’t regularly read newspapers or magazines, says David Fleischer, a political scientist at the University of Brasilia.

“TV stations don’t blast [Rousseff] like the press does,” Fleischer says.

In stark contrast to much of the world, the printed word is growing in Brazil, as literacy and news consumption rise. Folha’s circulation increased 2% in print and 300% online last year.

“More diversity in the media would be good for the country,” Davila says. “I just really don’t know why it’s not happening.”

For now, neither Rousseff nor retired port worker Da Silva seems worried.

“Everyone who travels around here can see clearly that Brazil has changed. Globo distorts the truth, yes. But it’s not so bad. Who cares? They can say whatever they want,” Da Silva says in a phone interview, and then breaks into laughter. “Actually, I’m watching Globo right now.”

Bevins is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.