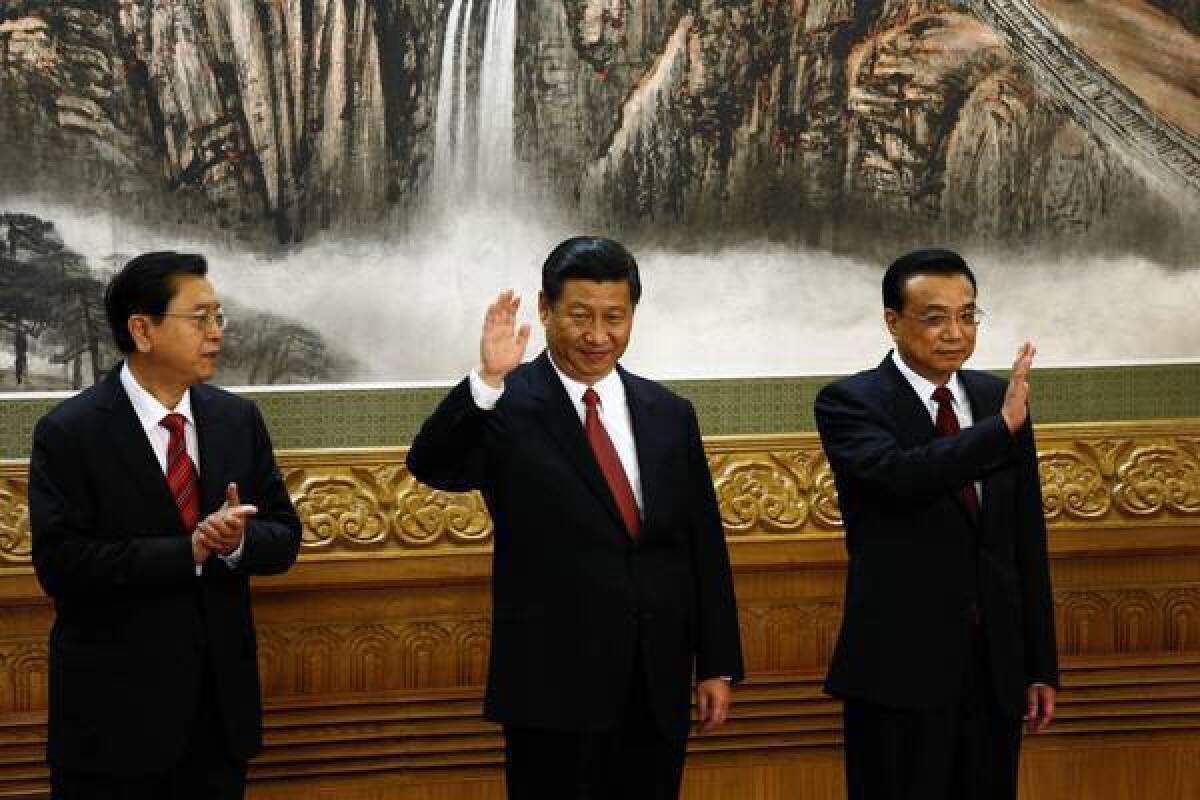

China unveils new leaders

BEIJING — China on Thursday unveiled the men who will lead the country for the next decade after a Communist Party congress that was more about pomp and pageantry than real political change.

With little deviation from the script, President Hu Jintao stepped down as party general secretary, a position he has held for the last decade, to make way for Xi Jinping, his long-ago-anointed heir.

Hu appears to be leaving office entirely, giving up even his position on the Central Military Commission.

In a time-honored tradition, the 59-year-old Xi and the rest of the top leadership were paraded out in a large conference room in front of a painting of the Great Wall of China to meet the news media. Guessing about who would be named to the all-powerful Standing Committee continued until the last possible moment, when the men stood on small numbers that had been pasted on the red carpet.

There were no real surprises, with the leadership opting for bland personalities with impeccable Communist Party bona fides over innovators.

Hopes for a more open China rest with Xi, whose father in the 1980s helped Deng Xiaoping pry open the economy. Xi is considered an affable pragmatist who climbed patiently through the ranks, serving as party secretary in Shanghai and Fujian and Zhejiang provinces.

Xi gave a brief speech, refreshingly free of jargon, in which he promised to crack down on corruption, bring the leadership closer to the people and improve living standards.

“The people’s desire for a better life is what we will fight for,” Xi told the assembled journalists.

Xi is to formally take over as president in March.

Li Keqiang, a vice premier who will likely step up to replace Wen Jiabao as premier, was also named to the Standing Committee. He is thought to be Western-friendly and one of the few senior Chinese leaders who can banter in English.

Otherwise, the party eschewed the U.S.-educated and Westernized.

Zhang Dejiang, educated in economics at North Korea’s Kim Il Sung University, came out as No. 3 in the order of seniority. He was followed by 67-year-old Yu Zhengsheng, Shanghai party secretary, who is a “princeling” from a prominent revolutionary family. His father was once married to Jiang Qing, who later wed Mao Tse-tung.

Liu Yunshan, the propaganda minister blamed by liberals for China’s stifling restrictions on film, publishing and the Internet, was elevated to the Standing Committee as well.

Wang Qishan, a former trade negotiator and banker who is one of China’s most seasoned financial experts, was a shoo-in for the committee. He also will head the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, overseeing the party’s promised campaign against official corruption, which was something of a disappointment to Western business leaders who had hoped he would handle the economics portfolio.

That job will go to Zhang Gaoli, probably one of the lesser-known personalities, an economist and former oil executive credited for overseeing the dramatic growth of Tianjin.

The Standing Committee, which is like a Cabinet but more powerful, previously had nine members but was reduced to seven to make leading by consensus easier.

“They wanted as little diversity as possible,” said Jin Zhong, a veteran political analyst and writer based in Hong Kong. “This congress threw cold water on the people who hoped for reform.”

Willy Lam, a China expert at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said there was some disappointment that Hu, once seen as a reformer, wasn’t able to make much progress in opening up the party during his two five-year terms.

“Even though Hu has been talking about democracy within the party, nothing substantial has been achieved in terms of reform. It’s a sad reflection on the state of affairs within the party,” he said. “It’s still a Leninist structure; it’s still politics of old men and women.”

Political analysts say the selection process even violated pro-democracy provisions of the Communist Party’s own constitution. That document calls for the congress’ delegates, 2,307 this year, to elect a party legislature called the Central Committee. The Central Committee in turn is supposed to elect the Politburo and the more elite Standing Committee.

The vote for the Central Committee was held in a secret session Wednesday morning as reporters were packed into a hallway behind locked doors. Footage broadcast later on state television showed the leaders and other delegates dropping their ballots into a red voting booth adorned with a hammer and sickle.

Actually, it wasn’t much of a choice. The day before, the party had held a “preliminary” vote. There were 224 candidates for the 205 seats — a key figure for Sinologists who gauge China’s glacial progression by the percentage more candidates there are than seats. This year it was 9.3%, just a hair more than during the last party congress in 2007.

However, there were hints that the process wasn’t entirely without a hitch this year. The state media did not release the names of the 205 selected candidates until the evening news — an unexplained delay, coming almost eight hours after the election.

It was expected that CCTV, the state broadcaster, would air the closing ceremony live, and party members among faculty and student bodies at some universities were instructed to watch. Instead, only excerpts were broadcast on the evening news.

“I think they didn’t want to take the chance of showing uncontrolled live images ... but rather prepare a carefully manicured version,” suggested one political analyst who was involved with the state television coverage.

With staging reminiscent of the old Soviet Union, the congress took place in the cavernous Great Hall of the People on Tiananmen Square, the interior draped dramatically with red curtains. At the conclusion, the delegates stood to sing “The Internationale,” the socialist anthem.

The leadership transition this year has been marked by fierce infighting — fallout from the purge of Bo Xilai, the charismatic former party chairman in Chongqing whose wife was recently convicted in the poisoning death of a British businessman.

Bo, once a contender for the top leadership, still has many supporters who see him as a latter-day embodiment of Mao’s vision.

“The whole meeting was very tense and uptight, more so than other congresses,” said Ho Pin, a publisher and political analyst. “The atmosphere was almost like a funeral.”

During the weeklong congress, Hu vowed China would not adopt “Western-style” reforms, a message that was loudly echoed in editorials in state media.

A long-anticipated revision in the party’s constitution, which reformers thought might reduce the emphasis on Mao’s teaching, turned out to be just a minor tinkering to pay tribute to Hu. The gathering also added language promising to better monitor corruption among party officials and protect the environment.

Jiang Zemin, the 86-year-old former leader, who was rumored to have died, was a major presence at the gathering, shown in almost all footage next to Hu, and the composition of the Standing Committee reflected his clout. Contenders for the committee who didn’t make the cut embodied yearnings for reform: Wang Yang, the party chief of economic powerhouse Guangdong province, and Li Yunchao, who was educated at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

As far as democracy within the party is concerned, China lags behind Vietnam and even the former Soviet Union, where the party central committee twice rejected official nominees for the top jobs, said Susan Shirk, chair of the 21st Century China program at UC San Diego.

Shirk noted, however, that the party elders have held at least two “straw polls” in secret sessions that led to the decision to push Xi into the leadership, followed by Li.

“You could say these are baby steps toward intra-party democracy,” she said.

Times staff writer Julie Makinen contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.