Mexico drug traffickers corrupt politics

Reporting from Patzcuaro, Mexico — There are few places in Mexico that better illustrate the way traffickers have corrupted the political system from its very foundation than Michoacan, the home state of President Felipe Calderon.

A relatively new and particularly violent group, La Familia Michoacana, is undermining the electoral system and day-to-day governance of this south-central state, pushing an agenda that goes beyond the usual money-only interests of drug cartels.

Whether by intimidation, purchase or direct order, drug gangs can sometimes dictate who is a candidate and who is not, and put some of their own people in races -- a perversion, critics say, of democracy itself.

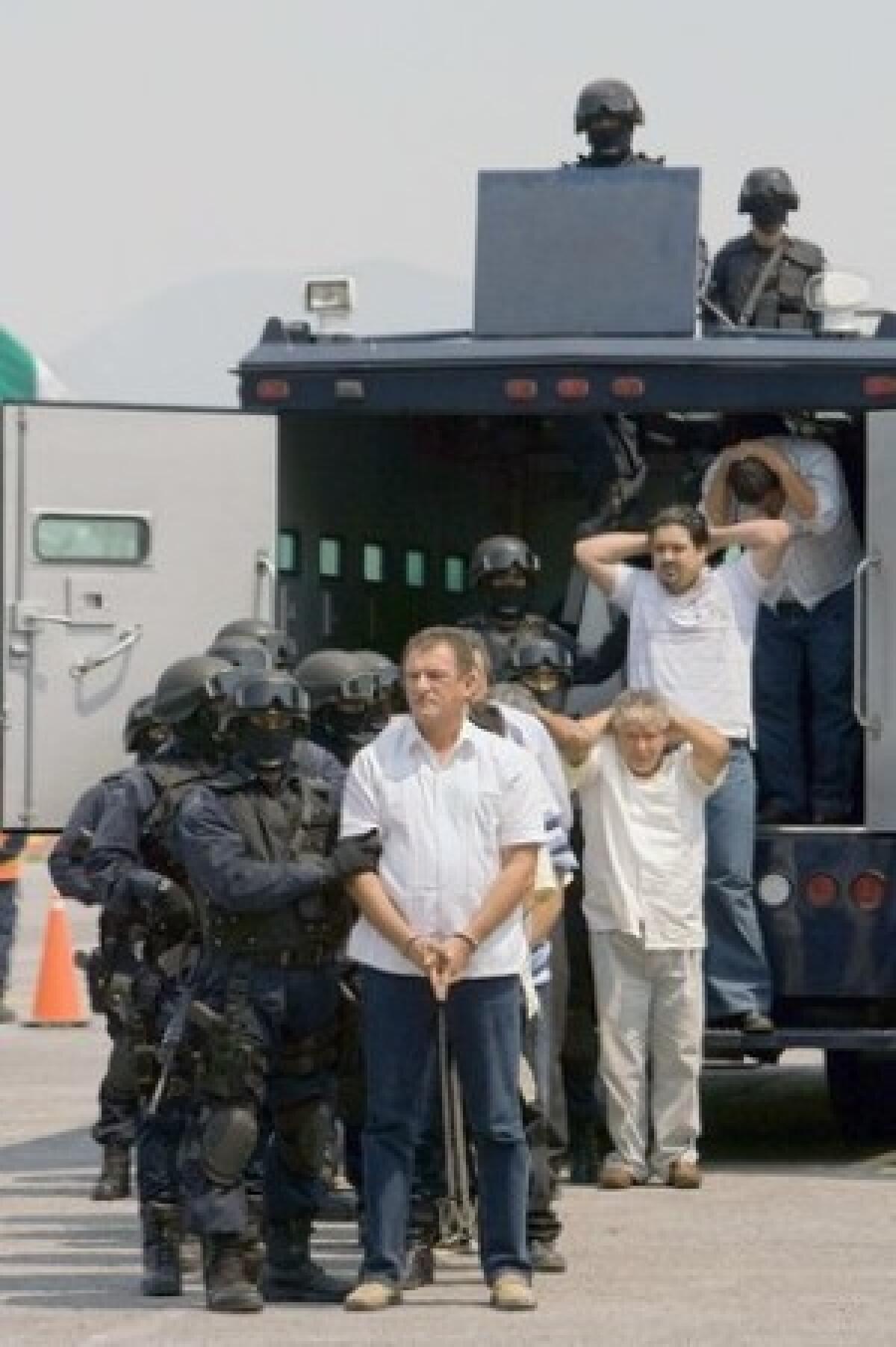

Just last week it became clear how deeply embedded La Familia is. Federal authorities detained 10 mayors and 20 other local officials as part of a drug investigation, saying the organized-crime group has contaminated city halls across the state. The roundup comes at the height of the electoral season, as Michoacan and the rest of Mexico approach local and national contests July 5.

Dozens of mayors, city hall officials and politicians have been killed or abducted in Michoacan as La Familia has extended its control in the last couple of years.

When congressional candidate Gustavo Bucio Rodriguez was slain at his gasoline station last month, authorities went out of their way to convince political leaders that he was the victim of common crime, showing them a surveillance tape of the killing by a lone gunman.

A few days earlier, the message was unmistakable. Nicolas Leon, a two-time mayor of Lazaro Cardenas, site of Michoacan’s huge port, was tortured and shot to death. Left on his body was a message signed “FM” (Familia Michoacana) warning that supporters of the Zetas, the enforcement arm of a rival trafficking group, would meet the same fate.

Unlike some drug syndicates, La Familia goes beyond the production and transport of marijuana, cocaine and methamphetamine and seeks political and social standing. It has created a cult-like mystique and developed pseudo-evangelical recruitment techniques that experts and law enforcement authorities say are unique in Mexico.

No party has been spared its influence or interference, politicians of all stripes said in a series of interviews conducted before the arrests of the mayors.

“It is a way to win power with fear, where the authorities either don’t have the capability to fight it, or have the capability but not the inclination,” said German Tena, president of the Michoacan branch of the country’s ruling National Action Party.

“There are mayors and politicians who ‘let things happen,’ and there are some who have sold their soul to the devil,” said a high-ranking Michoacan state official who agreed to discuss the sensitive topic of corruption in exchange for anonymity.

Generally, though, traffickers’ political influence in Michoacan has less to do with winning office and more with controlling officeholders, to create a buffer of protection that allows their business to proceed unimpeded, said a security advisor to Calderon.

Several political leaders said they tell candidates to keep a low profile and counsel supporters not to be too public about their endorsements. And they rarely publicize the illegalities they see.

“If we know or hear that a candidate is mixed up with narcos, we are not going to denounce it,” said Fabiola Alanis, who heads the Democratic Revolution Party in Michoacan. “It is not my job. It would put my candidates in danger. There is nothing to guarantee that they would wake up alive.”

The Obama administration recently added La Familia to its “kingpin” list, a designation that makes it easier for U.S. authorities to go after its assets, including any money in U.S.-owned banks.

“La Familia is absolutely a priority,” a senior U.S. law enforcement official said. With its swift rise to the short list of dangerous cartels, La Familia is “a modern success story in Mexican narcotics trafficking,” the official added.

And with similar speed, La Familia has established footholds in the United States. The organization has drug-running operations in 20 to 30 cities and towns across the country, including Los Angeles, the official said.

For decades, Michoacan has been popular with traffickers, who were attracted to its fertile soil, abundant water, the rugged hillsides that provide cover and the Pacific port that eases transport. Especially in the rough, sparsely populated southern tier of the state known as the Tierra Caliente (Hot Land), a few gangs profited from vast marijuana plantations and, later, dozens of methamphetamine labs.

La Familia emerged this decade as a local partner of the so-called Gulf cartel, whose operatives were moving into the region along with their ruthless paramilitary force, the Zetas. La Familia and the Zetas gradually muscled out most of the other gangs, and La Familia announced its dominance by tossing five severed heads onto the floor of a dance hall in the Michoacan city of Uruapan in September 2006. The gruesome calling card soon became all too common in areas where drug traffickers settle accounts.

Upon assuming the presidency in December of that year, Calderon launched the first of tens of thousands of troops against drug traffickers here.

Nonetheless, La Familia is stronger today than ever. It has expanded into the neighboring states of Guerrero, Queretaro and Mexico, which abuts the national capital, Mexico City, while battling remaining pockets of the Gulf cartel.

La Familia also has steadily diversified into counterfeiting, extortion, kidnapping, armed robbery, prostitution and car dealerships. The group offers money or demands bribes; increasingly, people in Michoacan pay protection money to La Familia in lieu of taxes to the government.

At least 83 of Michoacan’s 113 municipalities are compromised by narcos, said a Mexican intelligence source speaking on condition of anonymity.

Purported leaders include Nazario Moreno Gonzalez, “El Mas Loco” (The Craziest), who is described as a religious zealot who carries a self-published collection of aphorisms (his “bible,” authorities say) and insists that the group’s traffickers and hit men lead lives free of drugs and alcohol.

Another leader, Dionicio Loya Plancarte, “El Tio” (The Uncle), is a former military officer. Both have million-dollar bounties on their heads.

They recruit at drug rehab centers and indoctrinate followers with an ideology akin to religious fundamentalism, complete with group prayer sessions. Some armed guards wear uniforms with the FM logo, witnesses say. Failure by a recruit to live by the rules is said to be punishable by death.

Moreno Gonzalez has also forbidden the sale and consumption of methamphetamine in Michoacan because it is such a destructive drug. It is for export only, primarily to the U.S. The Mexican army recently seized 200 pounds of ready-to-ship meth in a single raid, and the attorney general’s office has identified 39 labs in the state.

Another leader, Rafael Cedeño Hernandez, was captured last month while he and more than 40 other alleged La Familia associates were celebrating a baptism in a fancy hotel in Morelia, the state capital. They were still in their party clothes -- Cedeño in a crisp white guayabera shirt, one woman in a yellow fluffy frock -- when police paraded them, handcuffed, before television cameras.

Cedeño’s brother, Daniel, was running for Congress. After the arrest, he quit the race.

Daniel Cedeño Hernandez was not the only candidate for national office accused of having ties to drug traffickers. Valentin Rodriguez, a powerful two-time mayor running for Congress in a district around Patzcuaro, here in central Michoacan, has fended off repeated accusations that he has worked with La Familia.

“I am completely clean,” Rodriguez told Mexican journalists in early April when the accusations surfaced again. “If those [jerks] have proof, let them show it,” he said.

Efforts during the last two weeks of April to reach Rodriguez, who goes by the nickname The Dagger, were unsuccessful. He grew up so poor, people who know him say, that he couldn’t afford to go to school. Today he has the largest avocado-packing plant in Michoacan, worth, by his own account, $30 million.

Rodriguez, who represents the Institutional Revolutionary Party, has acknowledged that he was questioned by federal prosecutors investigating drug trafficking. He was never formally charged.

Last week, another congressional candidate was gunned down (he survived) in Michoacan; Julio Cesar Godoy, a congressional candidate who is the brother of the state’s governor, was hauled in for questioning as part of the narco-politics investigation; and the body of a founding member of Godoy’s party was discovered in neighboring Guerrero a month after he was abducted.

In 2007, two Labor Party candidates in a local race were intercepted on a road in the Tierra Caliente by gunmen who handed a cellphone to one of them. At the other end was this candidate’s just-kidnapped wife, begging for her life. The demand: Drop out of the party and run on behalf of another party, to ensure its victory. They did, and the party won.

The story is told by Reginaldo Sandoval, president in Michoacan of the Labor Party, who was himself abducted, held for a day and ordered to silence his criticism of the government and organized crime and to leave the state.

“It is difficult for us to work without fear, especially for those candidates who have a possibility of winning,” said Sandoval, who remains in Michoacan. “We are at the mercy of the organized criminals and drug traffickers. We have lost the drug war.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.