Historic, once-bustling bazaar in Syria now a battleground

- Share via

ALEPPO, Syria — The familiar passageways have turned hostile, the comforting labyrinth now a maze of menace.

But Abu Taher threaded his way Tuesday through the alleys of Aleppo’s ancient Souk Madina, past piles of debris and charred storefronts, determined to see whether his textile shop had survived the recent conflagration. He came alone, risking his fate to the hidden gunmen seeking targets.

“It’s our livelihood,” he explained, abruptly bursting into tears, a man of 60 weeping amid the desolation.

PHOTOS: Living under siege: Life in Aleppo, Syria

Abu Taher found little sympathy, however, from a group of armed rebels camped out in front of a trashed pistachio emporium, 50 yards from the front lines and the current range of government marksmen. The rebels have seen many of their comrades killed as they battle the forces of Syrian President Bashar Assad.

“Why are you crying about a shop [when] people are dying?” one combatant with a Kalashnikov rifle dismissively asked the grieving merchant, who, like others, requested that he be identified with a nickname for security reasons. “Go back home, uncle.”

His shop, as it turned out, was unscathed. But some nearby establishments had not survived the onslaught.

The devastating fire that broke out late last month as fighting raged around the ancient bazaar is said to have destroyed hundreds of shops. Many owners still don’t know the fate of their businesses, their families’ lifelines.

Aleppo’s Old City, a United Nations-recognized World Heritage Site, has become a battleground. The core of the covered market is abandoned and dangerous, a place where rival snipers train their rifles and shells fall almost every afternoon. The shoppers and tourists are long gone.

The nearby medieval citadel, the city’s signature landmark, remains a government stronghold. The historic Umayyad Mosque, meanwhile, has been a site of combat, changing hands in the last week. As of Tuesday, it was back under government control.

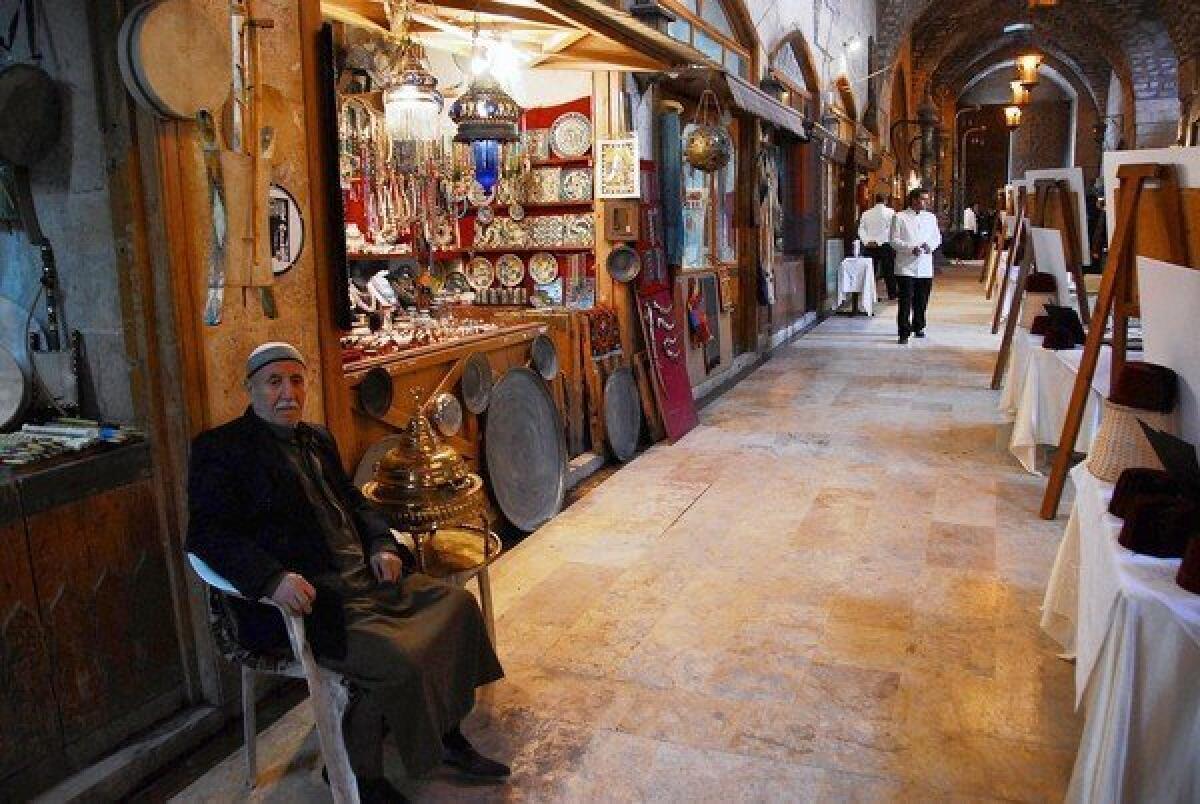

Preservationists worldwide have expressed concern for the fate of the sprawling bazaar of Aleppo, a Silk Road terminus. Once bustling, the passages beneath its vaulted stone arches are now lifeless except for scurrying cats and the occasional militiamen making their way through, wary of an attack that could come from any direction.

Opposition activists said government shelling started the recent blaze; wood structures and combustible goods such as clothing and draperies quickly fed the flames. But so far the cause remains unclear.

On Tuesday, several journalists who entered the dense warren saw considerable damage, but the epicenter of the blaze was unreachable because of snipers. Under rebel escort, visitors were advised to dash past various crossings on which government riflemen were said to have their weapons trained. Gunfire echoed in the passageways. The rebels, with little formal military training, have difficulty securing the jumble of lanes and alleys, making it a shooter’s paradise.

Inside the souk, which is divided between rebel and government positions, an acrid odor hangs in the air. In several areas, shops show signs of fire damage. Others seem to have been looted. Shelling and fighting have reduced some sections to debris piles. Merchandise such as homemade brooms and rope lies scattered about.

Many establishments have shut down, including several of Aleppo’s celebrated soap makers, whose olive-oil-based products fetch premium prices in Paris and Berlin.

Still, in the sections that were accessible Tuesday, the stone archways, hanging lamps and massive wooden doors separating areas of the market appeared largely intact. But the souk is a massive place, covering several square miles, and the full extent of the damage remained unclear.

Whatever the fate of the bazaar’s physical structure, the fighting has been a disaster for residents and merchants.

Shop owners speak of distant forebears who sold goods from the same spot. The souk has long been a mainstay of the economy in Aleppo, Syria’s commercial hub.

“I think it was my grandfather’s grandfather who started here,” said one businessman.

Many Old City denizens seem to bristle with resentment at the opposition force, which they view as having brought war to their enclave. Most of the fighters appear to be from rural areas, fueling the sense of division between rebels and residents.

In Aleppo, bread lines are ubiquitous, garbage sits on the streets and government artillery and aerial strikes continue without letup. Attack helicopters and fighter jets regularly make passes over the city, sometimes firing, sometimes simply stoking fear or observing ground movement.

Yet some shops still do a brisk business selling vegetables and other goods on the streets of the Old City, and children play in the alleyways. People are trying to go about their normal lives.

“Prices have gotten so high, and there is shelling every day,” said one elderly shopper, who was quickly quieted by another man.

Residents clearly refrain from speaking negatively in front of the rebels. Shopkeepers out on the streets seem to avoid eye contact with the rifle-wielding young men patrolling the cobblestones.

“We’re caught between two sides, and we’re with neither of them,” said one merchant, who, like others, wanted to give only his first name, Hussein.

As the fires raged Sept. 29, Hussein recalled, he and others used buckets of water from an ancient bathhouse to try to douse the flames. No firefighters responded.

Hussein said a wooden stairway, said to date from the 12th century, collapsed as volunteers struggled to control the blaze. The flames were finally stopped three doors from his family’s clothing shop, he said.

His family has no plans to leave the souk, said Hussein, the eldest male of eight children, all involved in commerce.

“Once you are from the Old City, it’s very hard to leave here, because it becomes part of you,” he said, standing beneath an archway, out of earshot of the nearby rebels and somewhat protected from the shrapnel.

Soon the afternoon shelling began anew, shaking the ground of the venerable Old City.

“This is a heritage we were proud of,” Hussein said. “Now we fear it will be gone.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.