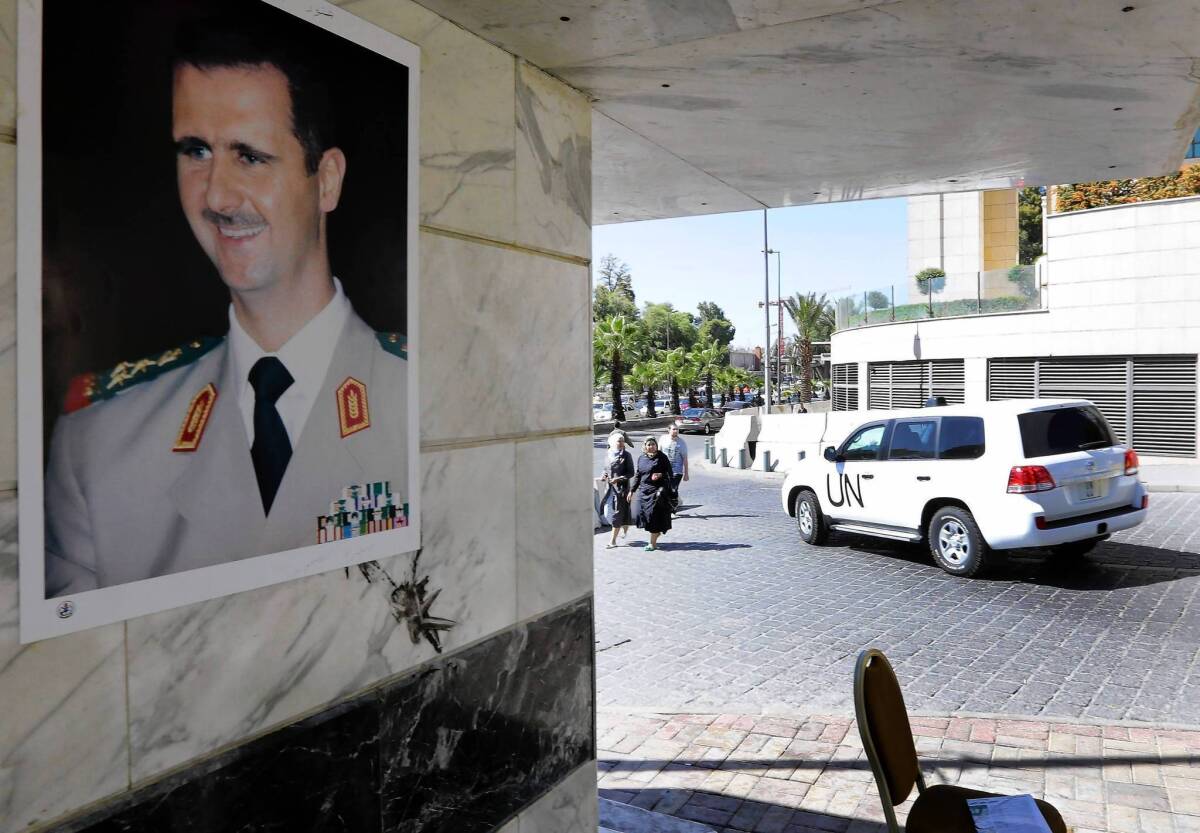

Push to eliminate Syria’s chemical weapons may extend Assad’s rule

- Share via

BEIRUT — For much of Syria’s civil war, President Bashar Assad has been a man in retreat. Rebels control vast stretches of his country. A little more than a month ago, he faced the prospect of U.S. military strikes that might have finally tipped the military balance.

But the U.S.-Russian deal to eliminate Syria’s chemical arms, which headed off a U.S. missile barrage, has changed that. Assad is now an essential partner in a process that will last until at least mid-2014, and could drag on much longer.

In a few short weeks, the push to eliminate Syria’s chemical weapons under international supervision has, in the view of many, in effect supplanted the goal of ousting Assad.

On Monday, Syria formally became the 190th nation to sign on to the Chemical Weapons Convention, the international treaty outlawing the use and production of such arms.

Assad’s surprise decision to allow the destruction of his chemical arsenal has “made a dent in the interventionist narrative that he’s an uncontrollable madman who can’t recognize diplomacy if it hit him in the face,” said Ramzy Mardini, an analyst based in Amman, Jordan. “That growing reality is favoring Assad, not the opposition.”

The turnaround has caused profound consternation among Syrian opposition figures and regional powers such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia that have strongly backed the rebels.

U.S. officials still insist that Assad’s departure is an essential element to any peace deal.

Secretary of State John F. Kerry on Monday repeated Washington’s long-stated policy that Assad must go as part of any revival of the long-stalled Geneva peace process, which calls for creation of a transitional administration in Syria based on “mutual consent” among parties on the ground. Although the Geneva guidelines do not bar current government officials from participating, Washington and its allies insist that Assad must resign.

“We believe that President Assad has lost the legitimacy necessary to be able to be a cohesive force that could bring people together,” Kerry said in London during an appearance with Lakhdar Brahimi, the United Nations-Arab League special peace envoy for Syria.

Nonetheless, analysts say the last thing U.S. policymakers want now is Assad’s hasty exit — especially with badly divided rebel forces increasingly dominated by multinational militant factions, including some linked to Al Qaeda. A steady stream of reports linking Syrian insurgents to executions, kidnappings and sectarian rampages has sullied the rebels’ image, alarmed U.S. policymakers and bolstered Assad’s support in Syria among his key constituencies, minorities and the urban elite.

A damning Human Rights Watch report last week implicated Syrian rebels in the deaths of scores of civilians during a summer offensive in the western province of Latakia, a stronghold of Assad’s Alawite sect. Militants from as far away as Europe, Morocco and Russia are pouring into Syria to join the fight.

Still, Syrian government forces appear to be holding their own and, in some cases, advancing. Assad’s authority in government-controlled areas of Syria extends not only to regular troops, but also to tens of thousands of loyalist militiamen who form a kind of parallel national army and wield considerable clout on the ground.

With the help of fighters from the Lebanese Shiite Muslim militant group Hezbollah, pro-Assad forces have managed in recent months to push rebels back from some areas around Damascus, the Syrian capital. They also have retaken the strategic town of Qusair and other territory in Homs province, securing a crucial corridor to the Mediterranean coast, a loyalist bastion.

For the moment, Assad is probably the only figure who can ensure implementation of the United Nations-backed blueprint to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons.

Assad “is very useful to the process, and I think that’s the reason he is being engaged,” said Andrew Tabler, a Washington-based Syria analyst who has long called for more robust U.S. intervention to help oust Assad. “Now, his usefulness will dwindle as the chemical weapons stockpile is destroyed.”

The elimination of Syria’s chemical stockpiles in the midst of a raging civil war poses an unprecedented challenge requiring “temporary cease-fires” in some areas, according to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, the Hague-based group overseeing the process. By some accounts, as many as seven Syrian chemical sites, including the sprawling Safira military complex outside the northern city of Aleppo, may be in areas where rebels are operating.

Though the U.S.-backed opposition has said it would cooperate with the chemical disarmament plan, there have been no such guarantees from powerful, Al Qaeda-linked factions such as Al Nusra Front and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. That raises the possibility that Assad’s troops may be called on to clear out rebel forces to ensure inspectors access to chemical facilities in contested areas.

Some fear Assad may try to delay the process beyond mid-2014, when the destruction of Syria’s chemical arms is slated to be completed. “Assad has an interest in dragging this out,” said Tabler, a senior fellow with the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

In recent public comments, as his forces have launched new thrusts in the north and outside Damascus, Assad has projected a defiant and self-assured tone.

The prospect of his ouster by opposition forces seems less and less likely. Even if Washington and its allies bolster arms deliveries to Syrian rebels, Assad retains strong backing and regular weapons shipments and economic aid from Russia and Iran.

The threat of direct U.S. intervention, his longtime fear, has dimmed with the chemical accord. Assad has even broadly hinted that he may run for reelection in national balloting scheduled for next year.

“Where is another leader who would be similarly legitimate?” Assad asked an interviewer for the German magazine Der Spiegel this month.

U.S. allies whose leaders view Assad’s ouster as an opportunity to reconfigure the strategic map of the Middle East complain that the sudden focus on eradicating Syria’s chemical weapons has overshadowed their larger objective. Kerry’s qualified praise last week of the Syrian president for cooperating with the chemical weapons plan stunned many.

“How could we praise someone who has killed more than 110,000 people?” a seemingly incredulous Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan said last week, citing the estimated death toll in Syria in 2 1/2 years of fighting. “I do not regard Assad as a politician anymore. He is a terrorist who kills with his state terrorism.”

Special correspondent Nabih Bulos contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.