In the library with a leading Islamic liberal

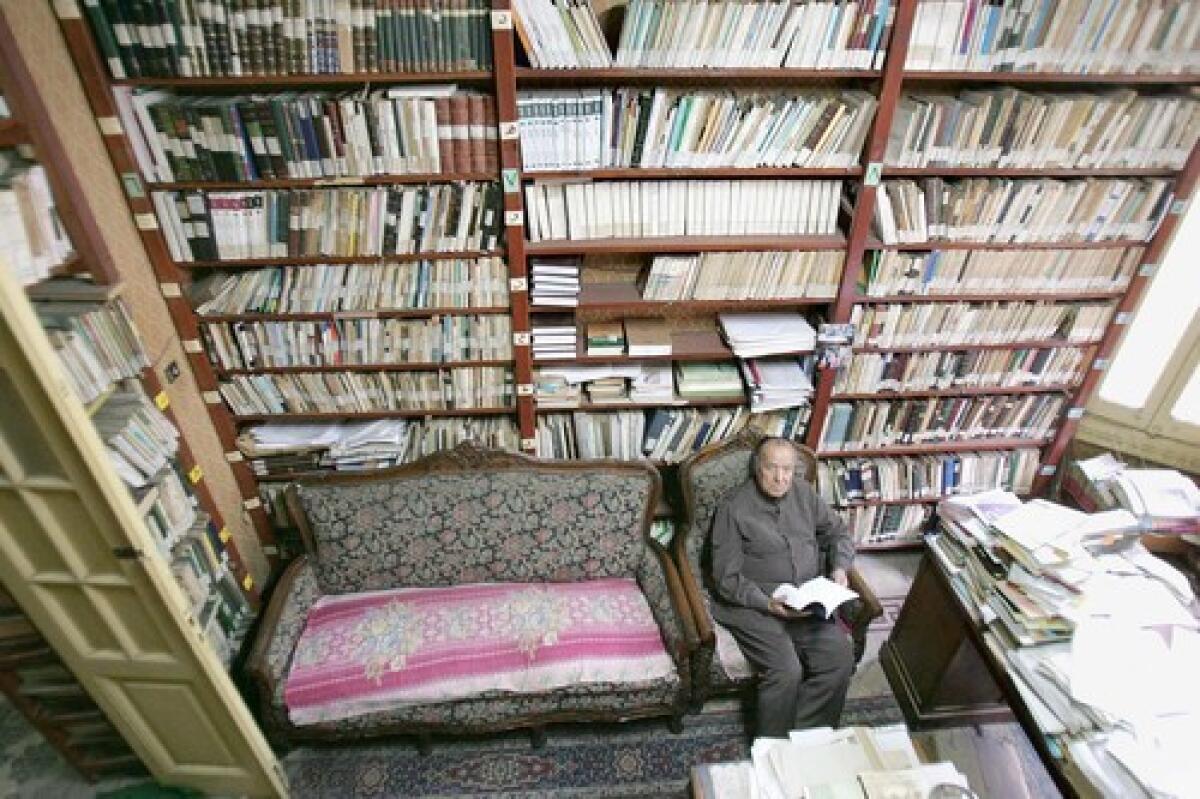

CAIRO -- So many books stacked like brittle armies in quiet rooms above the traffic on a street of tailors and mechanics.

A slight man in a brown suit, whose smooth face belies his 88 years, can slide one from shelves of thousands, brush its cover and tell you a story, whether it be about jihad, St. Francis of Assisi or the labor movement of the 1930s. He has written 120 books himself, many of them about Islam, which to him has too long listened to the restrictive voices of the past.

Gamal Banna is one of Islam’s leading liberal thinkers. For years he has accused conservative clerics of running a dictatorship that has kept the Koran from speaking to a world much changed since the 7th century revelations of the prophet Muhammad. Banna, whose long-dead brother led a fundamentalist movement that inspired many of his critics, relishes unnerving opponents with opinions that strike at convention.

He supports the right of women to lead Friday prayers: “How can we make an ignorant man an imam and not a learned lady?” He holds that unmarried couples’ kissing does not lead to sin: “An insignificant act the [conservatives] say is a step toward adultery.” And his next book deals with relations between men and women under Islam.

“Islam has to go through its own reformation, and this will take 50 years at least,” said Banna, who wears thick glasses and has dark, combed-back hair brightened by coils of white. “We are four centuries behind Europe on thoughts about politics and religion.

“I’m advocating radical change. We reject the clerics who rely on 1,000-year-old [teachings] which cannot live in this age.”

Banna will not be here in half a century, but at a certain point, vision and hope become strong counterbalances to time. He speaks with force, but quietly. His mind racing, he sits at a desk walled high with books and files, as if he’s peering out from a bunker. His assistant offers chocolates and disappears, retreating to a computer in another room, the peck of keystrokes echoing through dust and distant car horns.

The old man’s critics are many; they regard him as a reckless interloper, a peddler of sacrilege, especially for his beliefs that smoking should not be forbidden during Ramadan fasting, that the veil is not an obligation in Islam and that the burka is a “crime that destroys the personality” of a woman.

“He is invading a field he has no knowledge of at all,” said Abdel Moati Bayoumi, a professor of the fundamentals of Islam at Al Azhar University in Cairo. “He doesn’t have the necessary background to understand the texts of the Koran. He doesn’t represent any intellectual current. He is just a showoff who wants to be famous by exposing nonsensical, unfounded ideas.”

The name Banna has resonated through Islam since 1928, when Gamal’s older brother, Hassan, founded the radical Muslim Brotherhood. The banned organization has sought unsuccessfully to rule Egypt through Sharia, or Islamic law.

The nation’s strongest opposition voice, the brotherhood has renounced violence at home but supports Hamas and other Arab militant groups deemed terrorists by the West.

Banna’s critics wonder how he can be so liberal when his brother was such an ultraconservative. Banna said Hassan, who was assassinated in 1949, would have changed with the times and settled the differences between the group’s fundamentalists and moderates. These rifts and constant arrests by the Egyptian government of brotherhood members have kept the group off balance despite its appeal among the middle and educated classes.

“The Muslim Brotherhood has lacked strong leadership since the days of Hassan,” Banna said. “They have not developed a coherent vision of political Islam. I told them: ‘You stay as an opposition group. You are not ready for the reins of power.’ They don’t live in the modern world. They don’t accept modernity, cinema, art. They live as if from five centuries ago.”

Such assessments come from Banna’s lips as if he’s polished them in his mind for years. He has lived through modern Egypt’s travails: the promise and then brutality under President Gamal Abdel Nasser; the peace treaty with Israel signed by President Anwar Sadat; and, for the last 27 years, the politically oppressive government of President Hosni Mubarak.

“The society is completely corrupted. The regime of Mubarak has failed,” Banna said. “The man has no imagination. . . . The question is what will come after him?”

But it is not the temporal that consumes this fidgety man, riffling through papers, flicking pages, seeking precedent and anecdote. He is concerned with the soul and the clearest path to God.

“Religious reform must come before political reform, because a man must be pure before he can change politics,” he said. “You need conscience before political reform will succeed. The Arab states won independence long ago, but they didn’t know how to benefit because independence came before religious reformation.

“You can’t create an Islamic state. It will fail, and this is the verdict of history. You must have democracy.”

The essence of the spirit, as Banna calls it, is found in the Koran. The problem for him is that much of Islam is based on the Sunnah, the collected sayings and practices of Muhammad handed down by tribal ancestors. He believes that many of these interpretations are locked in a centuries-old mentality.

Banna’s solution, which angers many clerics, some of whom accuse him of coming close to heresy, is to bypass the Sunnah on many ecclesiastical questions and seek guidance directly from the Koran.

“We have no need to abide by the rules of our ancestors. We have to go directly to the Koran itself,” he said. “We need our own modern interpretation of the Koran. Many of the clerics can’t even dream of our modern age.”

He stood and stepped to a bookcase. He pulled a cracked binding from the shelf. “Look, you will be astonished,” he said. The book was published in 1899 in St. Petersburg, Russia; it was about the prophet Muhammad and Muslim customs. “Here’s one from India, 200 years old.”

Banna walked into another room, past rows of books on unions and labor movements, which years ago were his passion.

“Look, this novel about St. Francis I really like, ‘Blessed are the Meek.’ ”

He held it for a moment and then turned to another shelf, stacked with books he had written. A man’s life on so many pages. He picked up his book on jihad.

True jihad, he said, is the struggle within; not to impose your religion, but to defend your belief.

Special correspondent Raed Rafei in Beirut contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.