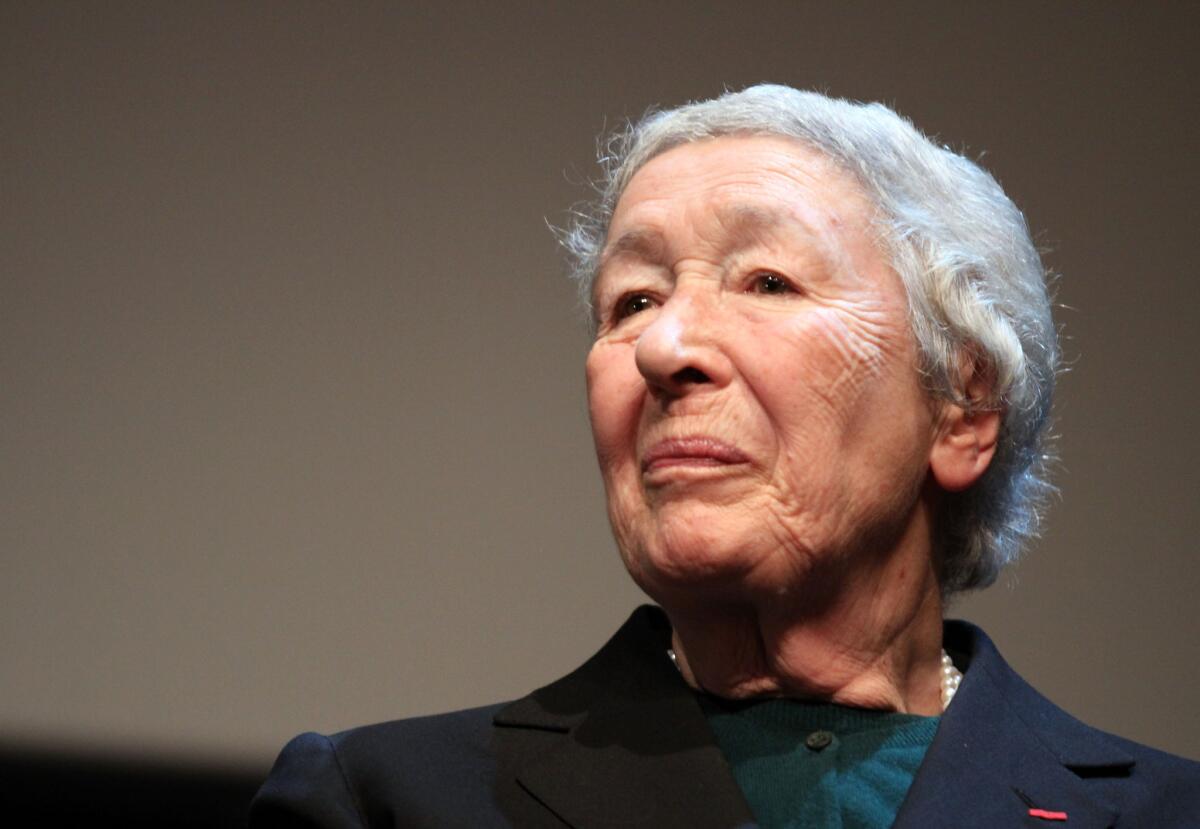

Gae Aulenti dies at 84; architect designed Paris’ Musee d’Orsay

Gae Aulenti, an Italian architect who attained international prominence turning old buildings into modern museums, including Paris’ Musee d’Orsay and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, died Wednesday at her home in Milan. She was 84.

Her family told Italian media that she had been ill for some time.

One of the few women working in postwar Italian design, Aulenti began her career designing furniture, lamps and other accessories. One of her most famous pieces is the Tavolo con Ruote (Table With Wheels), an elegant postmodernist work consisting of a thick square of glass on industrial casters that is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

She also designed showrooms for Olivetti and Fiat, opera sets for Milan’s La Scala, the garden at a Tuscan villa, and a Rodeo Drive boutique for fashion designer Adrienne Vittadini.

But the work that brought her the widest acclaim was refashioning historic structures into museums.

Musee d’Orsay, her most famous project, was a 1900 Beaux Arts train station that she transformed over a period of several years into a sleek and glamorous home for Impressionist masterpieces and other art.

San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum had been a library in its previous life, defined by a mock-classical style popular in the early 20th century. In Aulenti’s hands it became an open, light-filled space with unexpected touches, such as a courtyard with volcanic stone floors and seating.

“Gae Aulenti had a very profound understanding of classical architecture ... but also an extremely modern sensibility,” said Emily Sano, who worked with Aulenti as director of the Asian Art Museum when the renovation was launched in the late 1990s. “She was also deeply humane. She really did understand how objects affect people both physically and emotionally.”

Aulenti, who also designed museum spaces in Barcelona, Istanbul and Venice, often provoked extreme reactions with her architectural adaptations. When the Musee d’Orsay opened in 1986 the critics’ reactions ranged from “fabulously eccentric” to comparisons with “a funeral hall ... an Egyptian burial monument.”

The architect, whom Sano described as a “tough, really brilliant woman,” brushed off the attacks by noting the public’s response: In its opening days, 20,000 people lined up to get in.

“We looked at the old station as a contemporary object, without history,” Aulenti, referring to the old Gare d’Orsay railway station, wrote in Architecture and Urbanism magazine some years ago. “We regarded the original architect, Victor Laloux, as a companion in the metamorphosis of the station into a museum.”

Aulenti was born Dec. 4, 1927, in Palazzolo della Stella, near Trieste, where her father worked as an economist.

“My parents really wanted me to be a dilettante, a nice society girl,” she said in a 1987 New York Times interview, “but I was rebellious. I enrolled in architecture school in opposition to their wishes.”

She was one of only two women in Milan Polytechnic School of Architecture’s 1954 graduating class.

Twice divorced, she is survived by a daughter, Giovanna, and a granddaughter.

After graduating from architecture school, Aulenti spent a decade working as an art director at the design magazine Casabella.

During the 1960s she began designing furniture while also teaching architecture at the University of Venice and Milan Polytechnic.

Part of a postwar group called Neo Art Nouveau, which defined itself in opposition to such masters as Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, she found inspiration in history, art, music and philosophy. In 1964 she won first prize at the Milan Triennale for her Picasso-influenced work in the Italian Pavilion.

In 1987 she received France’s highest honor, Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, for her work on the Musee d’Orsay. She was the first female architect named to the order.

“Architecture is a male profession,” she told the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera last year, “but I never took notice of that.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.