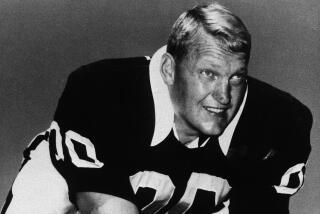

Jack Tatum dies at 61; Oakland Raider safety whose hit left Darryl Stingley paralyzed

Jack Tatum, the storied Oakland Raiders safety best known for landing the hit that paralyzed New England receiver Darryl Stingley, has died. He was 61.

Tatum, among the most feared and respected NFL players of his era, died of a heart attack Tuesday morning in an Oakland hospital. He had been waiting for a kidney transplant.

Tatum was a sledgehammer in Oakland’s “Soul Patrol” secondary of the 1970s that also included safety George Atkinson, cornerback Skip Thomas and Hall of Fame cornerback Willie Brown.

“As many big plays as Jack made, it let you know this guy knew where to be when the chips were down,” Atkinson said. “Guys didn’t want to come across the middle because getting hit by him was like getting hit by a truck. He was devastating with his timing and his angles of contact.”

Never was that more true than on Aug. 12, 1978, in an exhibition game against the Patriots, when Tatum hit Stingley on a pass over the middle. The collision broke Stingley’s fourth and fifth vertebrae, leaving the receiver almost totally paralyzed from the neck down. (Stingley, who died in 2007 technically had “incomplete quadriplegia” because he had limited use of his right arm.) He is believed to be the only NFL player to have suffered that degree of paralysis as the result of a football injury.

“It was a slant and they throw it in the middle,” John Madden, Tatum’s former coach, recalled. Tatum is “going for the ball, Stingley is going for the ball. Stingley leaves his feet, they have a collision, and Stingley doesn’t get up. Even saying that, you get that feeling in the pit of your stomach. That’s something no one wants. You never want to hear about it. You never want to see it.”

Outside of his close circle of friends, who swear he had an easy smile and infectious laugh, Tatum largely kept to himself in public settings, which only seemed to make him more intimidating. Madden said the Stingley hit affected the Raiders star.

“He never talked about things, and you couldn’t get him to talk about it,” the coach said. “It was something that ate on him for his whole life.”

Tatum was not contrite about the hit.

“I’m not going to beg forgiveness,” he told the Bergen County (N.J.) Record in 2003. “That’s what people say: You never apologized. I didn’t apologize for the play. That was football.”

A year later, however, Tatum told the Oakland Tribune he had tried to visit Stingley in an Oakland hospital shortly after the incident but was turned back by the receiver’s family. They never met after the hit.

After Tatum’s left leg was amputated below the knee as a result of diabetes in 2003, Stingley was interviewed by The Times. He said he no longer harbored ill feelings about the hit.

“I forgave Jack Tatum years ago,” Stingley said. “You forgive, but you just don’t forget. In my heart and in my mind, I’ve forgiven him and moved on. As a result, I was able to go on with my life without looking back with bitterness.”

Born John David Tatum in Cherryville, N.C., on Nov. 18, 1948, Tatum was raised in Passaic, N.J. He played under Woody Hayes at Ohio State, was first-team All-Big Ten player from 1968 to 1970, and a unanimous All-American in 1969 and 1970, even garnering Heisman Trophy votes. He was selected 19th by the Raiders, a team desperate for some defensive stability.

“The year before we drafted Jack, we weren’t a good tackling team,” Madden said. “When you go through a year and you don’t tackle well, that really bugs you. So when we went into the draft I said, `I want to get the best tacklers we can find and I want to take them early. We took Jack, and we never had a tackling problem the rest of his years there.”

Tatum played nine seasons for the Raiders, intercepting 30 passes and helping the franchise win the Super Bowl after the 1976 season. He played his final season with the Houston Oilers in 1980.

Madden said that Tatum’s “toughness, tackling ability, and what he represented just rubbed off on everyone.”

Years after his playing career, when he worked first as a Raiders employee and then as a member of the NFL’s so-called fashion police, making sure players’ uniforms were to code, Tatum — with his cowboy boots, thick moustache and wild, salt-and-pepper hair — cut an imposing figure.

“Even when he was in his late 40s, he was an intimidating guy,” said sportscaster Greg Papa, longtime radio play-by-play man for Raiders games. “He’d sit way in the back of the bus, and I’d envision that’s the way he did it when he was playing.

“He wasn’t real talkative. You had to engage him. It wasn’t like hanging around Ted Hendricks or Phil Villapiano, one of those larger-than-life Raider characters. Jack was soft spoken. But when other guys were around him, he was a commanding presence.”

As much as Tatum intimidated, he also inspired. Hall of Fame safety Ronnie Lott, who was to the 1980s what Tatum was to the 1970s, called the Raiders standout one of his football heroes.

“One of his greatest hits I ever saw was him hitting Earl Campbell at the goal line,” Lott said, about the Oilers running back. “There’s a fearlessness that comes with those hits. It’s a commitment to hit a person as if you’re going to hit all the way to his back side. It was unbelievable. When a guy hits like that, it’s almost as if the air just gets still.”

Even though the safety co-wrote a book called “They Call Me Assassin” after his career ended, Tatum was never called “The Assassin” during his playing career, Madden said.

“After the book, people started to call him `The Assassin’ and say that that was his nickname, which was never true, and that he called himself an assassin, which he didn’t,” Madden said. “The story is that he’s a high school All-American and he’s recruited to Ohio State as a hitter. And he’s praised to be a hitter. And he plays at Ohio State and he’s an All-American, because he’s a hitter. And he goes to the pros and is a first-round draft choice because he’s a hitter.

“And then he hits a guy, the guy doesn’t get up, and they call him an assassin.”

Tatum is survived by his wife and three children.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.