Joan Sutherland dies at 83; ranked among the most powerful divas of the 20th century

Joan Sutherland, the Australian tailor’s daughter acclaimed as “La Stupenda” during a nearly 40-year operatic career and rated by many critics as the most powerful and technically perfect diva of the 20th century, has died. She was 83.

Sutherland died Sunday at her home near Geneva, Switzerland, after a long illness, her family announced.

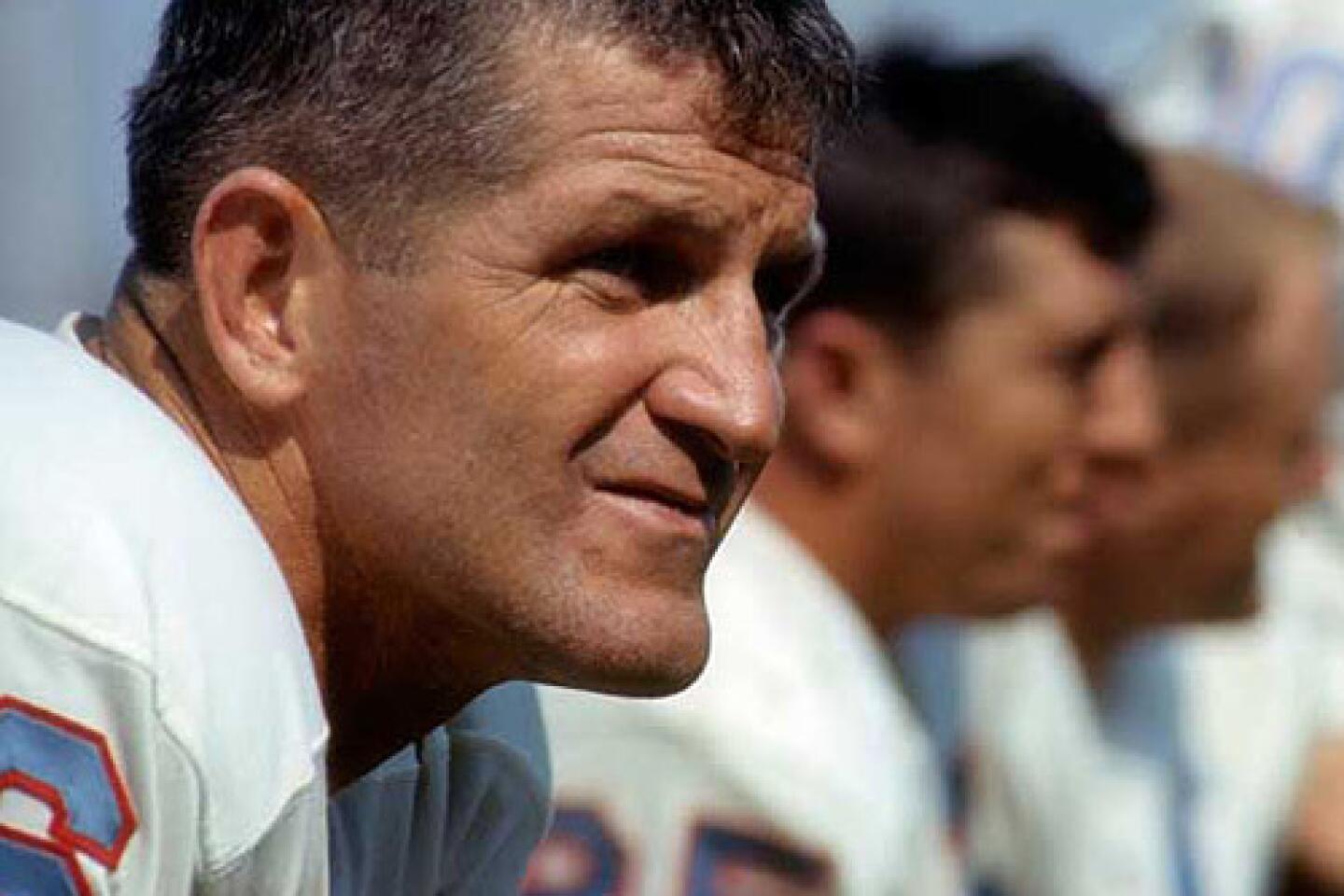

Sutherland achieved stardom in 1959 with a celebrated turn in the title role of Gaetano Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor” at London’s Royal Opera House. By then she was 32 and had been with the company for seven years, making a name for herself in a wide assortment of roles until the perfect one came along. She had been performing professionally since she was 18, and from the age of 16 she had steadily devoted herself to broadening her vocal scope and perfecting her technique.

Her most important teacher was Richard Bonynge, a pianist she met when they were teenagers in Australia — and who would become her husband and regular conductor.

Sutherland’s triumph as Lucia spurred a return to prominence for the “bel canto” style for which she became famous. Building on the achievements of Maria Callas, Sutherland went on to re-establish the long-neglected bel canto (Italian for “beautiful singing”) repertoire of the 18th- and 19th-century composers Donizetti, Rossini and Bellini. Beverly Sills and Sutherland’s close friend, Marilyn Horne, were among those who subsequently took advantage of opera companies’ renewed interest in the style, in which composers lavished their music with trills, extreme high notes and other musical ornamentation intended to showcase the singer’s brilliance.

Sutherland’s “magnificent voice,” interpretive strength and revival of “bel canto works that had nearly been forgotten” together “ensure a permanent place for her in the history of our art,” opera star Placido Domingo said in a statement Monday.

He recalled first working with her in “Lucia di Lammermoor” in 1961, and “being amazed by her technique but also grateful for her and Richard’s simplicity and kindness.... We will all miss her very much.”

Sutherland’s voice, wrote Winthrop Sargeant in a 1972 New Yorker profile, was “as large as that of a top-ranking Wagnerian soprano. It had a range that stretched from A below middle C to F, or even to F-sharp, above the staff. It also had the sensuous, womanly quality that proclaims the great diva. But the most glorious thing about it was its astonishing agility and its uncanny accuracy.”

Times critic Martin Bernheimer wrote of her 1966 concert debut at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion: “One never ceases to be astounded by the way Miss Sutherland manipulates a basically large vocal instrument as if it were as slender and inherently flexible as the coloratura sopranos.” It was “even rarer,” he added, that she wielded it not to overwhelm, but with unstrained ease, musicality and taste. Sutherland’s only flaw, for most critics, was what Bernheimer called “her mushy … diction.”

She was born Nov. 7, 1926, in Sydney, Australia. Her musical journey began when she was a small girl, seated on the piano bench alongside her mother, Muriel Sutherland, a highly regarded amateur contralto, as Muriel did vocal exercises. Her father, William, a Scottish immigrant, died when Joan was 6. The family moved in with her grandparents, and her mother and older half-siblings from William’s previous marriage went to work.

After high school, Sutherland worked as a typist, but she was able to pursue voice training, thanks to lessons she’d won in a contest. Victory in another local competition brought her a series of bookings in small towns in New South Wales. There she met Bonynge, her sometime accompanist. Those earnings, and a larger cash prize from a national voice contest, bankrolled Sutherland’s move to London, where she lived with her mother, studied at the Royal College of Music and began auditioning for the Royal Opera at Covent Garden. She made it on her third try, in 1952.

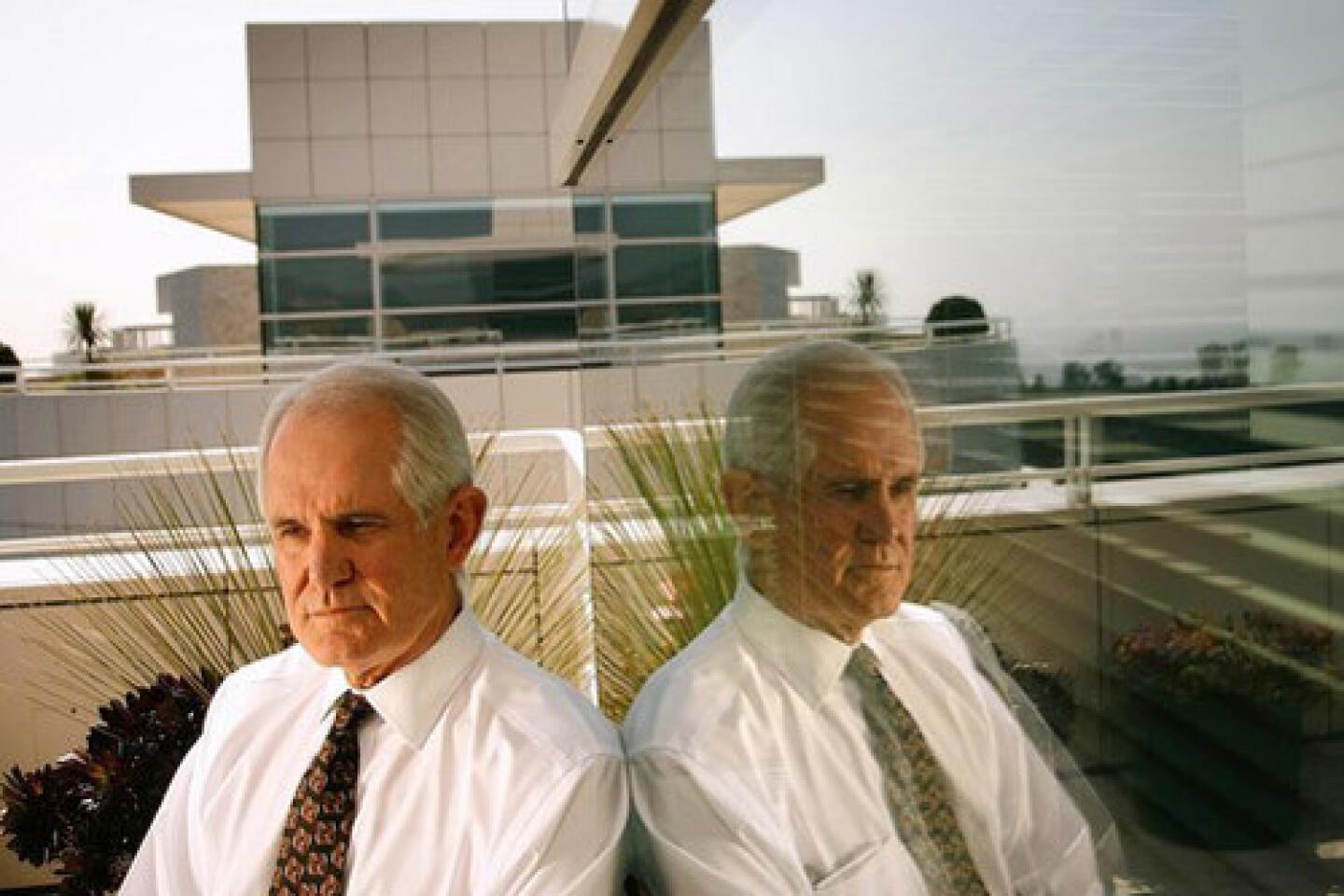

By then, Bonynge, who also had pursued musical studies in London, was coaching her; they married in 1954. Later, some critics were less than enthralled that Sutherland and Bonynge remained joined at the hip professionally. Recalling a 1972 recording of Puccini’s “Turandot” Sutherland made with Zubin Mehta, conductor-musicologist Will Crutchfield, then a critic for the New York Times, speculated in 1986 whether that disc’s virtues might have been repeated more often had she gone in for more outside collaborations. “Her singing there is tremendously vivid, charged with a relish she has rarely shown for music so far away from her home base of bel canto virtuosity,” he wrote.

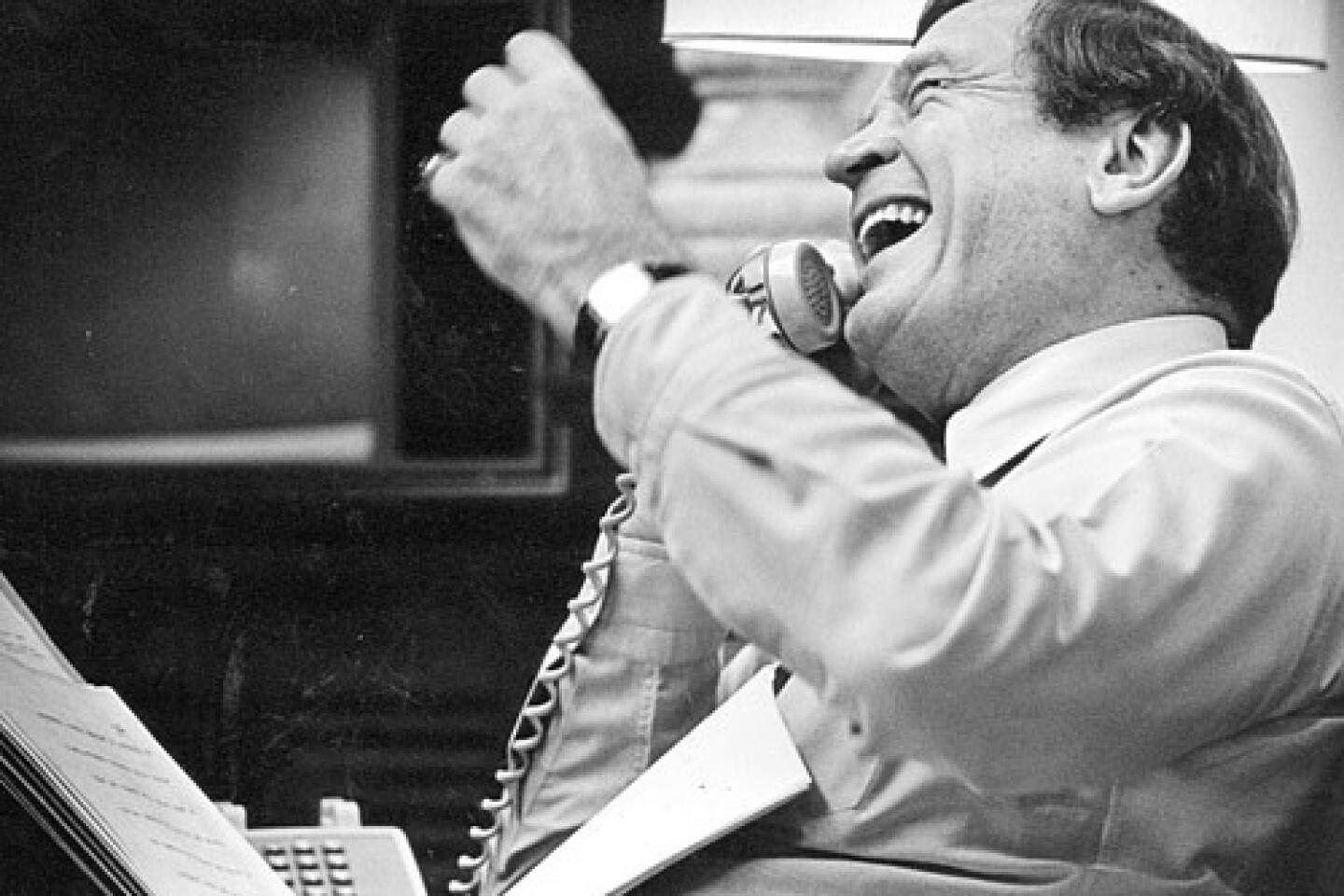

But Sutherland was happy to stand by her man: “For me he is the perfect conductor,” she told the New Yorker. “He knows how to allow for breathing, and he has a complete knowledge of how I feel and what I am capable of.” She and Bonynge (pronounced Bonning) continued to tour together until 1990, when Sutherland retired at 63.

One of her signature recordings is “The Art of the Prima Donna” (1960), but Sutherland was known for doffing the prima donna mantle when she left the stage. Music journalists often noted her down-to-earth personality, her typically good-humored disposition and her ability to negotiate an operatic career with a minimum of backstage conflict and drama. She preferred to go straight home after performances, rather than basking in the after-hours limelight.

“I’m a mum,” she told the British newspaper, the Guardian, in 2002. “I never thought of becoming a diva. I just wanted to sing the roles and get on with my work. I used to come to the theater in a taxi, not in some Rolls-Royce. I didn’t have time to do all that silly stuff.”

She was made a Dame of the British Empire in the late 1970s.

While her career was long, it wasn’t always easy. From her days as a company member with the Royal Opera during the 1950s, Sutherland coped with dental woes, severe sinus problems and chronic back distress.

But when caught up in the exultation of performance, she told the Australian newspaper the Advertiser in 1979, there was no pain. “When one is singing high and loud it’s as though one is in light air, high up on a mountain. I feel a lightness and a dizziness. Exhilaration, too,” she said. “I’ve never smoked marijuana, but I fancy it might be the same sort of feeling.”

She is survived by Bonynge; their son, Adam, and two grandchildren.

mike.boehm@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.