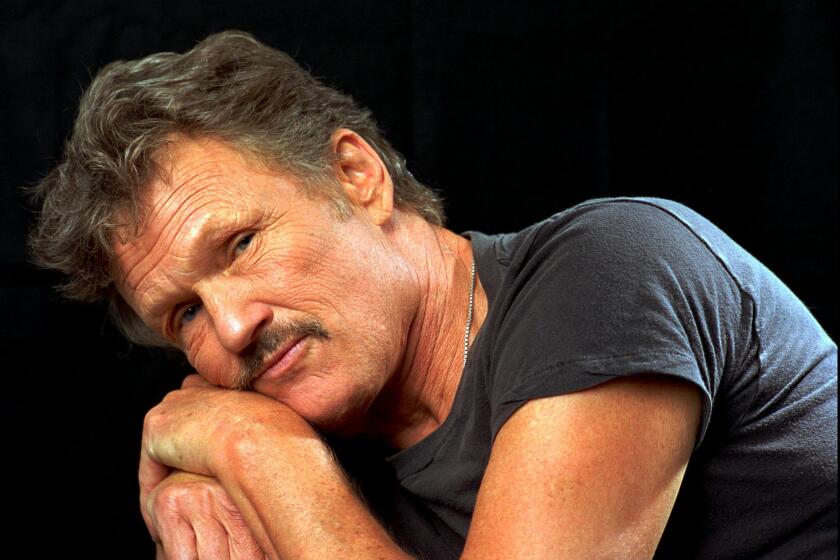

William T. Cartwright dies at 92; rescued Watts Towers

If William T. Cartwright hadn’t gotten lost on his way to visit an aunt in 1959, the Watts Towers might not have been saved.

Cartwright was trying to find Lynwood, but soon realized he was near the famed folk art towers and took a detour to see them. Shocked by what he found, he quickly set about trying to rescue them.

The mosaic-encrusted spires, created by Italian immigrant Simon Rodia over more than three decades, had been abandoned since the artist moved away in 1954. Five years later, Rodia’s house had been lost to a fire, gates to the property stood open, and the area was littered with debris.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

Cartwright, who ended up buying the towers with a friend and helped start a nonprofit to preserve them, died Saturday at a hospice in North Hills. He was 92.

Although he had various ailments, the cause was mainly old age, said his son William T. Cartwright Jr.

When he first laid eyes on the towers, Cartwright was a graduate student in film at USC and he later became an Emmy-winning documentary film editor and producer. Days after seeing the towers, he returned to the fanciful structures with Nicholas King, an actor and photographer’s assistant. From neighbors, they learned that ownership of Rodia’s property had passed to a local dairy worker. They soon found him and arranged to buy the complex for $3,000.

“We knew we had to do something that we believed should have been done before us: preserving something that needed it and not abandoning it,” Cartwright told The Times when King died at 79 in April 2012.

The men soon discovered that the structures were headed for demolition. With friends and local residents, they formed a nonprofit group, the Committee for Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts, to help fight City Hall and save them. The men transferred ownership of the property to the group, and Cartwright served as its first chairman.

Before the towers could avoid the wrecking ball, they had to survive a test in which the tallest spire was subjected to 10,000 pounds of pressure. The structures came through.

Because Cartwright recognized that the towers were “an important international treasure,” he had the vision to rescue them, Jeanne Morgan, a charter member of the committee, said this week. “They would not even exist today had he not done that.”

William Tilton Cartwright was born Aug. 25, 1920, in St. Louis, Mo. His father, Carroll, was a car dealer; his mother, Flora, became a cosmetics buyer for Saks Fifth Avenue. He grew up mainly in St. Louis and San Antonio, and enrolled at Washington University in St. Louis. He earned a bachelor’s degree in English, although World War II interrupted his schooling.

Trained as a naval aviator and photographer, Cartwright served in the Pacific theater as a Marine Corps fighter pilot, according to his son. In March 1945, Cartwright survived a crash into the sea when his aircraft was hit or malfunctioned after a bombing run. He broke several vertebrae and was rescued by a Navy destroyer.

After college, he worked as a photographer and filmmaker in Europe for the U.S. Agency for International Development, then attended film school at USC but dropped out before completing his graduate degree.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

For the David L. Wolper production company, Cartwright edited a number of documentaries. They included two highly regarded “The Making of the President” films. He earned an Emmy for editing for the first one, about the 1960 presidential campaign, and shared an Emmy for the second film about the 1964 race.

He shared in a third Emmy in 1989 for co-producing a documentary on actress Lillian Gish for the “American Masters” series on PBS.

Producer Terry Sanders, who worked with Cartwright on several films, including the 1994 Oscar-winning documentary about Maya Lin, designer of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, described him this week as a superb editor who “wasn’t afraid to stand up for his ideas.”

Cartwright also edited a number of feature films, including two about World War II, “The Devil’s Brigade” (1968) and “The Bridge at Remagen” (1969).

In addition to his son William, his survivors include another son, Robert; a brother, Carroll L. Cartwright; and three grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.