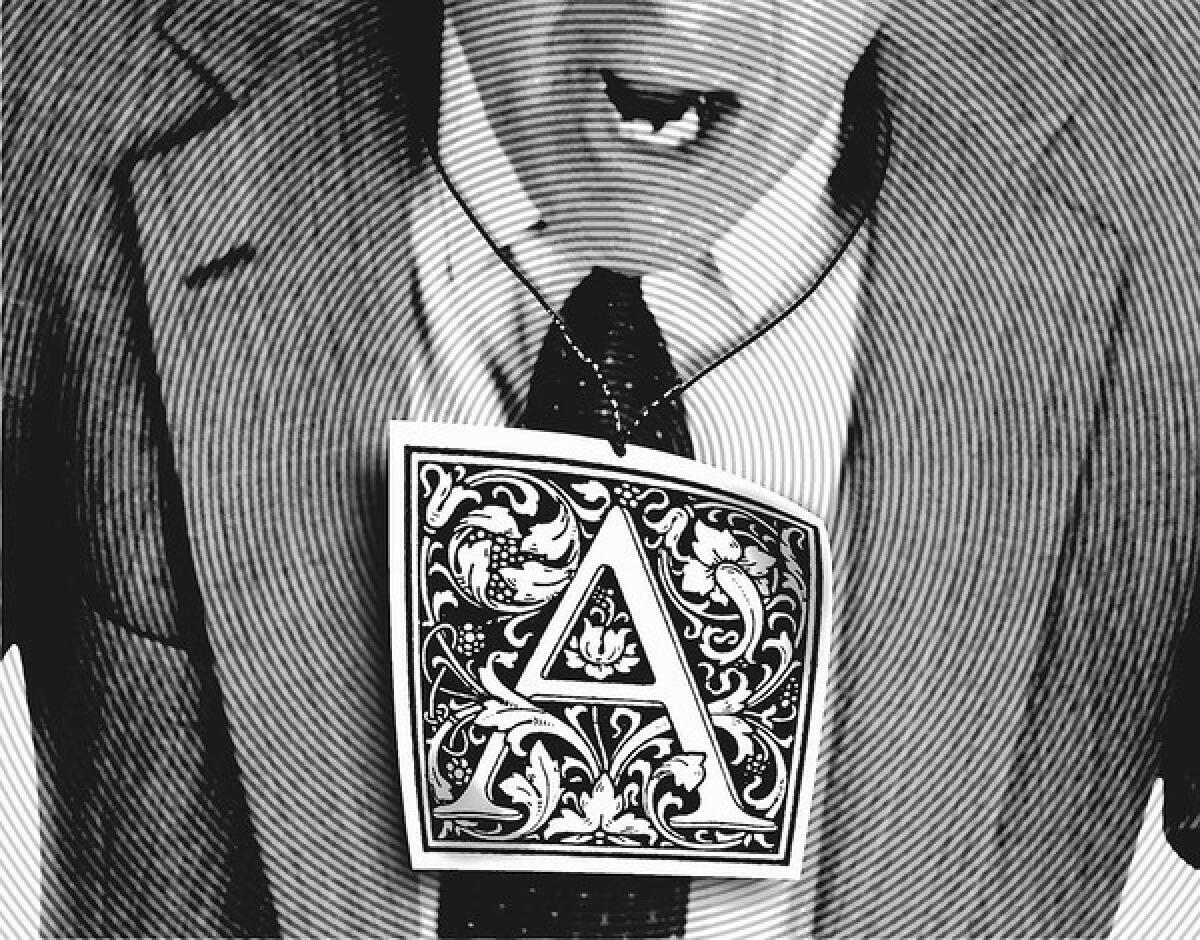

Exhibit A-word

Other vulgarities have their defenders, but the “A-word” gets little respect, whether it’s referring to someone’s anatomy or his character. As a term of abuse, it’s Exhibit A for those who bewail the coarsening of American culture. Is it really worth giving any thought to? Actually, yes.

Granted, we should use it sparingly. The word may no longer shock, but it is crude, as it has to be so we can make our feelings fully known when a neighbor starts his leaf blower at 7 a.m. But the discomfort about hearing it shouldn’t carry over to hearing about it. Precisely because it is coarse, it’s a window on our attitudes about how we should treat each other. And it offers a much more truthful picture of the problems vexing our public life than those simplistic op-ed harangues about a rising tide of incivility and an America split into two nations, the courteous and the crude. In fact, when we use the A-word, we become a citizen of both: If it’s the height of rudeness, it’s also our reflexive response to it.

Whether we utter or mutter it, the A-word comes immediately to mind when we encounter someone with a culpable obtuseness, a swollen sense of entitlement. I think of a story I heard from a Texas friend who found himself on 9/11 at a Hertz agency in Manhattan amid a crush of people all desperate to get home to their families. A man walked in, pushed his way to the front and asked loudly, “Where’s the gold card line?” You can be sure that every person in that room was thinking the same three-word sentence.

Used in this way, the word is actually a rather recent addition to our moral inventory. As a term of abuse, it was invented by World War II GIs — the first military leader tagged with it was George S. Patton — and it wasn’t until 1970 or so that it entered general usage, a term you could expect to encounter in Neil Simon plays and Woody Allen movies. It replaced “heel” as a reproach for men who mistreated women, and it nudged aside Holden Caulfield’s favorite put-down, “phony,” adding a note of abjection and self-delusion that was missing in those earlier words.

But the A-word doesn’t simply name a pathology; it prescribes a response to it. When somebody behaves like a jerk, we’re entitled to be a jerk in return, with an audible show of disrespect. (You can’t apply the word without swearing at someone, after all.) Sometimes we’re all but obliged to respond this way. When a friend tells you her husband has been having an affair with the baby sitter, what other word can demonstrate the full force of your indignation and solidarity?

The moral principle inherent here was dramatized in the character of Dirty Harry, so different from the heroes portrayed by John Wayne in an earlier age. Surrounded by A-word archetypes — the officious superiors, the bleeding-heart liberals and, of course, the sociopaths he brings to ground — Harry responds with a volubly sadistic pleasure (“Make my day”), offering all of us the thrill of watching someone do terrible things to someone who manifestly has it coming.

That principle — call it Dirty Harryism — has become part of the cultural wallpaper. In Donald Trump’s “Apprentice” boardroom, and in political campaigns, on talk radio and cable “news” shows, in blog posts and in the comment threads of the Internet, the object is to diminish your adversaries to contemptible jerks, so as to have the satisfaction of provoking and abusing them without any qualms of conscience

True, every age thinks it’s ruder than the one that preceded it, which is why we always describe courtesy as old-fashioned. Yet as historians remind us, public life was pretty vitriolic in earlier times too. In fact, our public discourse is no more scurrilous now than it was in the age of FDR or Lincoln. But those earlier ages couldn’t touch us for bad faith or schoolyard tribalism — or for the access that turns Dirty Harryism into a 24/7 spectacle and an online game that anybody can play.

Half a century ago, the columnist Westbrook Pegler could write savagely about Eleanor Roosevelt and compare Jews to geese (“They foul everything in their wake”), but his vituperation and anti-Semitism were heartfelt. He would have been mystified by Ann Coulter’s vile-with-a-smile charge that the 9/11 widows were enjoying their husbands’ deaths. She didn’t care about them; the point of the remark was to enable her political soul mates to revel in the thought of the sputtering indignation it would evoke in liberals.

To label somebody with the A-word is to give yourself permission to respond in kind, on the grounds that he has it coming. We appeal to that principle all the time in daily life, but like the word itself, there’s a time and place for it. It may justify your berating that guy who pushes through to the front waving his gold card. It’s a little more problematic when it leads people to applaud the congressman who yells “You lie” during a presidential address.

Focus on the A-word and you come to a different picture of the “crisis of incivility.” It isn’t the sign of a moral breakdown induced by Hollywood, the Internet or the entitlement culture. It doesn’t grow out of a dearth of moral feeling but an excess of it, in the corrosive delusions of righteous indignation. As Walt Kelly might have put it, we have met the assholes, and they are us.

Geoffrey Nunberg, a linguist, is a professor at the UC Berkeley School of Information. His latest book is “Ascent of the A-word.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.