The doping scandal (cont.)

Major League Baseball suspended a dozen players — including three all-stars — for the rest of the regular season Monday for violating the league’s ban on performance-enhancing drugs, and it ordered one of the game’s all-time best sluggers, Alex Rodriguez, off the field through 2014. It was a headline-grabbing crackdown that, in an encouraging sign, drew cheers from some big-league players. But it also suggests that baseball needs to do still more to deter players from trying to advance their careers by enhancing their body chemistry.

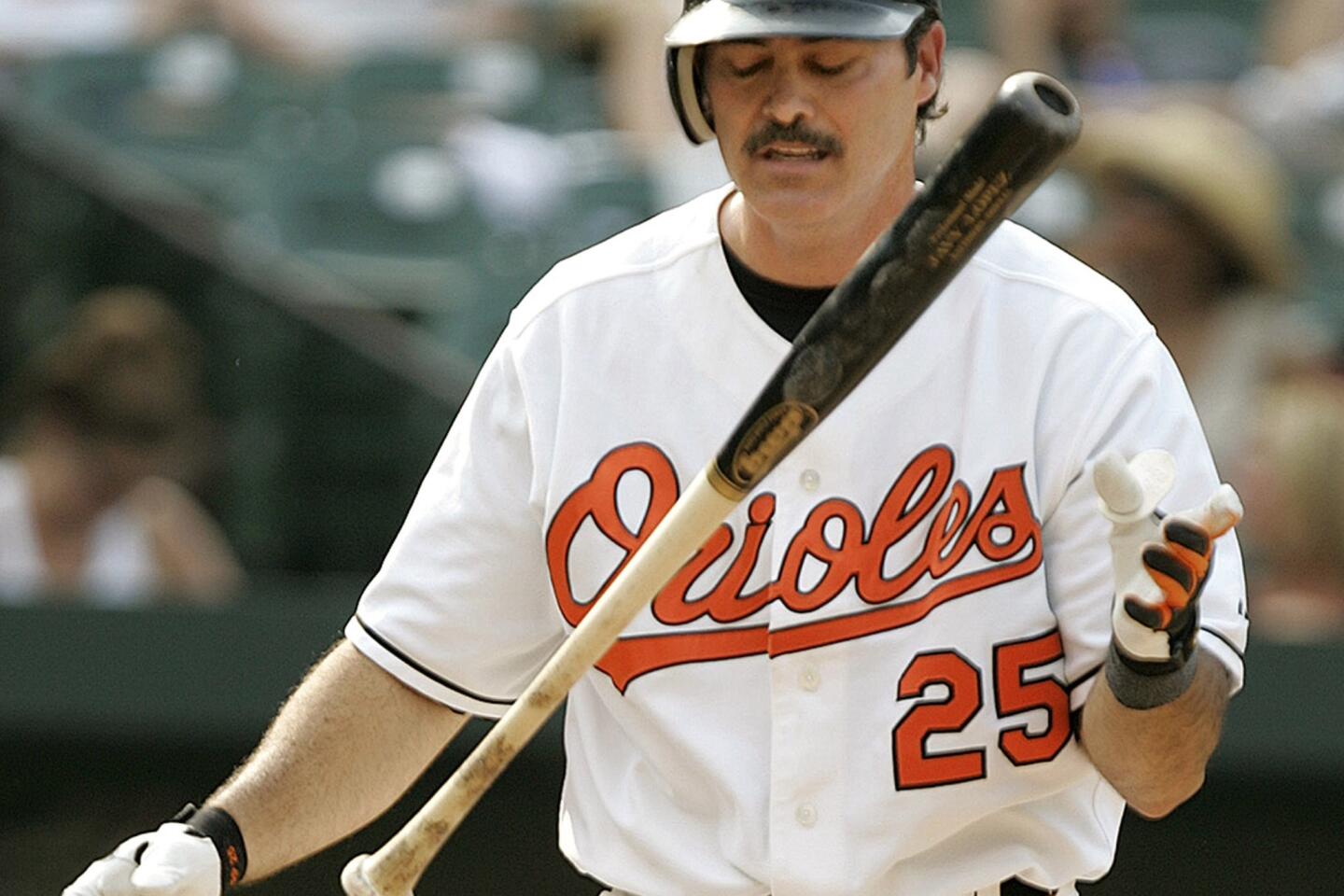

The 13 players suspended Monday — all of whom, save Rodriguez, accepted the sanction without appealing — are the latest to be brought down by the scandal at Biogenesis, a now-closed anti-aging clinic in southern Florida. None of the players were tripped up by the league’s vaunted drug-testing regimen; instead, they were exposed by a whistle-blower and the Miami New Times tabloid.

That’s not to say the league’s testing program, which has gotten steadily tougher since it began in 2005, is ineffectual. Four other players connected with Biogensis failed drug tests in 2011 and 2012 — three of them all-stars too — and all were handed suspensions ranging from 50 to 65 games.

Still, the scandal shows that determined cheaters can often stay a step ahead of testers, even when the regimen is as stringent as baseball’s. Some fans argue that the league should admit defeat and let the players do as they please. But that’s ridiculous. It would turn the game into a competition between doctors, not athletes, and would send a dangerous message to kids around the world, whose path to adulthood is challenging enough without steroids, human growth hormone and synthetic testosterone.

The pall cast by dopers also taints the accomplishments of all their fellow ballplayers. Increasingly, major leaguers recognize the threat that dopers pose to the game’s popularity and to their livelihoods, and they’re pushing the league for a more effective deterrent. Some have suggested increasing the penalty for first-time offenders, which now stands at 50 games without pay; others have talked about voiding contracts. The latter is the more promising route, given how much it could cost a player who uses a banned substance.

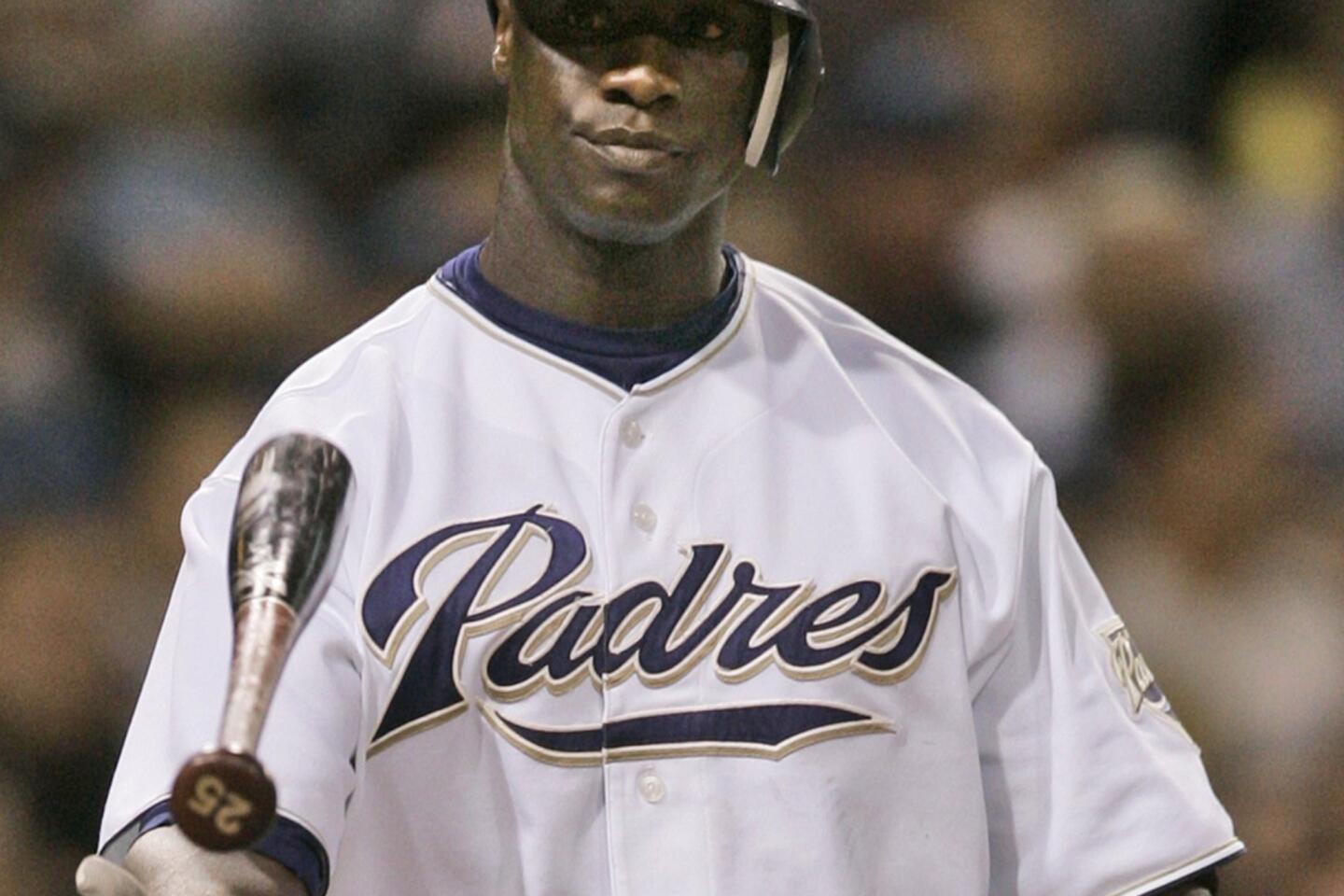

Thus far, though, owners have continued to give star players big contracts even after they admit to using performance-enhancing drugs. A case in point: Outfielder Melky Cabrera signed a two-year, $16-million deal with the Toronto Blue Jays in 2012 after serving a 50-game suspension. “He’s still a good hitter, on the stuff or not,” Blue Jays manager John Gibbons told USA Today. The penalty for violating the league’s drug policy would have to be significantly more painful to overcome that kind of incentive.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.