California’s Inland Empire

At night, I can hear the soft thumps as the rats land on my roof. They launch themselves from the branches of the apricot tree because they want to get inside my attic, into a house with heat.

The house next door, and the one next to that, have been empty since October. Their yards have gone feral, with hundreds of dandelion heads glistening gray in the night.

The rats are cold and hungry. The skunks have a den somewhere next door, where the metal shed was dismantled. Opossums, raccoons and lizards have colonized the abandoned yards on my block in Riverside. And it’s spooky, at night, to see so much darkness, to hear skittering, to keep an eye out for homeless people trying to break in and sleep, to listen for the sounds of desperate humans and animals.

Last week, a woman stole a pair of shoes right off my neighbor Maria’s front porch. Maria woke her son, who ran down the street and confronted the woman. She threw the shoes back at him. After a pair of clippers disappeared from my yard, I’ve started taking ladders and anything else of possible worth inside at night.

Our mailman, Randy, said this week that from what he sees in his letter bag (he reminds me that Americans have no secrets from the letter carrier), about one in eight homes in our neighborhood are in foreclosure or a few months away. The street already has six empty houses, some vacant for nearly a year. And people walking aimlessly in the street make life eerie and uncertain.

Here in the Inland Empire, we joke that our people are canaries but we don’t die.

Our foreclosure rate was the highest in the country for many months; Riverside County’s unemployment rate is 12.2%. But we do recession better than many places. We have experience. In the 1980s, we lost Kaiser Steel and many other manufacturers; from 1992-94, the unemployment rate for the Riverside-San Bernardino metro area averaged 10%, with an astonishing 12.1% in July 1992.

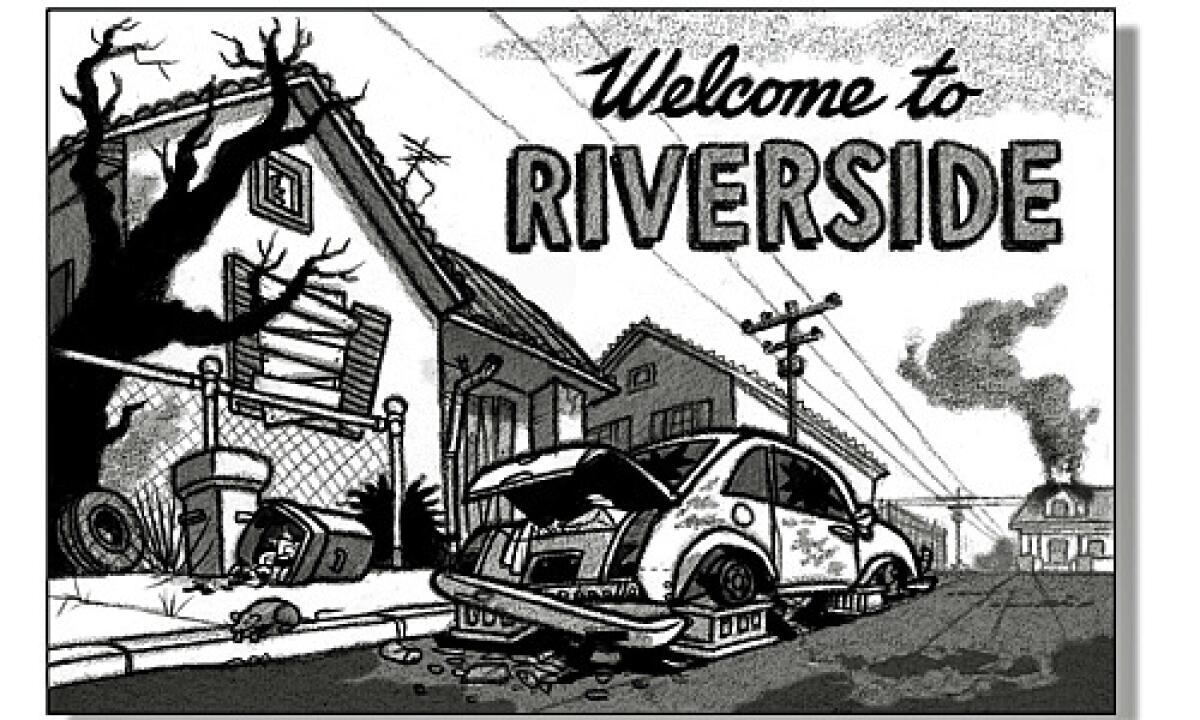

But this feels different. More desperate. Last year, after the price of copper skyrocketed, metal theft was rampant; thieves stole catalytic converters from parked cars, brass plaques from headstones and monuments, faucets and bushings from fire hydrants, copper wire from schools and parks. Thieves strip foreclosed homes, identifying them by “Bank Owned” signs in the dead lawns. Water heaters, copper pipes, electrical equipment -- all torn from walls and floors, homes destroyed.

I haven’t slept well for about a year. For a while, I woke up at night to check on my daughter’s Honda, which was broken into repeatedly. We knew it was a prime target. But recently it was stolen from in front of her friend’s house, in the 15 minutes she left it to go inside. On Presidents Day, my ex-husband and I drove to a towing yard in San Bernardino near the Colton border to retrieve what was left of the car when police found it. The guy who brought it to me shook his head.

Stripped. Everything gone but the fast-food trash the thieves had strewn on the floor. “I’ll call the salvage guy for new door panels and seats,” my ex-husband said. Then he rolled his eyes. “He only takes cash, but my tax refund’s gonna be an IOU, right?”

We drove through streets of boarded-up bungalows, the neighborhoods of old California now turning back to wild oats and silvery foxtails so high the windows were obscured. Men wandered the potholed streets looking like something out of a current-day Steinbeck novel.

To say we might lose “community” is too simple. We are already more isolated and urbanized than in the past. But to lose the community on my street, the street I’ve lived on for 22 years, breaks my heart.

We watch out for each other. A neighbor with orange trees brings me bags of navels, which I share with other neighbors. I give Maria eggs from my chickens and winter tomatoes and oranges, and she brings us foods from her native Philippines -- chicken adobo and pancit.

But increasingly there are things we can’t help each other with. Down the block, my neighbors -- waitresses and home day-care workers and contractors and retired people -- are all nervous about whether they’ll have jobs tomorrow. One neighbor sold many of her belongings last year in a series of yard sales, trying to make house payments; her husband, an adult-education teacher, was furloughed for the summer, and his hours for this school year were cut. They are filing for bankruptcy.

A few days ago, police were at Maria’s; someone had tried to carjack her son at gunpoint for his truck. And from my kitchen window, I saw police at a house on the next street. After work, my youngest and I smelled smoke on that street, so several neighbors and I ran to see whether the elderly widows on the block were OK. The fire was put out quickly, but one man said to me, “A bad day on this street.” Earlier that morning, police arriving to evict a woman found her dead. A woman in her 30s, in a rental house, who’d lost her job some months before and was being evicted, had hanged herself.

None of us can get her out of our minds, because we didn’t help her. We didn’t know. She hadn’t been here long. I can see the roof of her house as I wash dishes, and when I go to bed, I can hear the rats gnawing at the chicken wire over the vents on my roof.

Susan Straight’s most recent novel is “A Million Nightingales.” On Monday: The view from South Los Angeles.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.