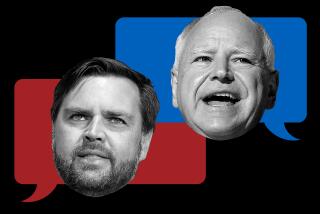

Cheney and Edwards Trade Accusations

CLEVELAND — Vice President Dick Cheney and Sen. John Edwards quarreled Tuesday in a hard-edged debate over honesty, credibility and the war in Iraq, each accusing the other of distorting facts and purposely misleading voters.

The two picked up on Iraq where their running mates had left off during a debate last week, with Cheney suggesting the invasion opened a crucial front in the global war against terrorism and Edwards charging the Bush administration with diverting resources from what he called the more important job of capturing Osama bin Laden and vanquishing Al Qaeda.

But the sharpest exchanges of the evening were less global and more intimate, involving the energy company Cheney used to run, Texas-based Halliburton Co., and Edwards’ congressional attendance record.

Edwards and Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kerry have repeatedly cited Halliburton, which has been awarded billions of dollars in contracts to rebuild Iraq, as a symbol of their charge that the Bush administration tilts toward the powerful and the well-off at the expense of ordinary Americans. Cheney, who ran the company between 1995 and 2000, continues to receive deferred payments from the company as part of his retirement package.

When Edwards mentioned Halliburton roughly halfway through the 90-minute debate, Cheney pounced.

“The reason they keep trying to attack Halliburton is because they want to obscure their own record,” the vice president said, speaking in his usual brisk, matter-of-fact tone. “And senator, frankly, you have a record in the Senate that’s not very distinguished.”

Cheney cited the North Carolina lawmaker’s frequent absences while campaigning in the last two years -- first for president and, since July, as Kerry’s running mate. “Your hometown newspaper has taken to calling you ‘Sen. Gone,’ ” Cheney needled. “I’m up in the Senate most Tuesdays when they’re in session. The first time I ever met you was when you walked on this stage tonight.”

Edwards responded sharply, reaching back to Cheney’s years in the House in the late 1970s through the 1980s and citing a number of his votes, including opposition to a federal holiday honoring Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, a resolution calling for the release of anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela in South Africa, the Head Start education program and funding for the Meals on Wheels program for seniors.

“It’s amazing to hear him criticize either my record or John Kerry’s,” Edwards said.

(After the debate, aides to Edwards said the men had met on at least two earlier occasions, at a February 2001 Senate prayer breakfast and at the swearing-in of North Carolina’s junior senator, Republican Elizabeth Hanford Dole, after her election in November 2002. Within 90 minutes, the Kerry campaign e-mailed a photograph of the two that it said was taken at the prayer breakfast.)

The format of the vice presidential debate, held on the campus of Cleveland’s Case Western Reserve University, was different than last week’s matchup between President Bush and Kerry, the senator from Massachusetts. Cheney and Edwards sat side by side at a horseshoe-shaped table and fielded questions on both domestic and foreign policy issues from moderator Gwen Ifill of PBS.

The tenor was also different, with the two candidates repeatedly challenging each other in a more aggressive and personal fashion than Bush and Kerry had. The evening’s pugnacious tone was set on the very first question.

Ifill asked Cheney about statements from Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld and L. Paul Bremer III, former U.S. administrative chief in Iraq, that appeared to contradict points the vice president had been making for months. In a speech Monday to the Council on Foreign Relations, Rumsfeld said he had seen no “strong and hard evidence” linking former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein to Al Qaeda.

In a separate appearance Monday, Bremer said the United States made two major mistakes in its invasion of Iraq: failing to deploy enough troops and failing to contain the violence and looting that followed the ouster of Hussein.

Cheney did not respond directly, but instead defended the invasion of Iraq as a necessary response in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. “What we did in Iraq was exactly the right thing to do,” Cheney said. “If I had it to recommend all over again, I’d recommend exactly ... the same course of action.”

Edwards turned to face the vice president and said, “Mr. Vice President, you are still not being straight with the American people.”

“There is no connection between the attacks of Sept. 11 and Saddam Hussein,” he said, as Cheney looked on impassively. “The 9/11 commission said it. Your own secretary of state said it. And you’ve gone around the country suggesting that there is some connection. There’s not.”

Cheney, who earlier had referred to an “established relationship” between Al Qaeda and Iraq, disputed that such comments meant he was linking Hussein to the Sept. 11 attacks.

Nearly half the debate was devoted to Iraq, reflecting the way the issue has dominated this presidential campaign.

Cheney accused Kerry and Edwards, who two years ago both voted for the congressional resolution giving Bush authority to use force against Hussein, of waffling on Iraq for the sake of expediency. He said Kerry supported the war when it suited him politically but changed his stance when former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean was dominating the Democratic nominating contest as the antiwar candidate.

“If they couldn’t stand up to the pressure Howard Dean represented, how could they stand up to Al Qaeda?” Cheney jibed.

Edwards responded that Kerry had consistently held the same position: that Hussein needed to be disarmed and the president needed the congressional authority to pressure him. But, Edwards went on, the administration rushed to war without giving diplomacy a sufficient try and ended up losing its focus on capturing Bin Laden and others responsible for 9/11.

At one point, Ifill asked Edwards to clarify Kerry’s statement in the debate Thursday with Bush that any preemptive military strike would need to pass a “global test.” Bush has seized on that remark in the days since that debate, suggesting Kerry would hand veto power over U.S. military policy to countries such as France.

Edwards accused Cheney and Bush of purposely distorting Kerry’s remarks, noting that he had said in the debate that no foreign country would ever dictate U.S. policy. “He will not outsource our responsibility to keep this country safe,” Edwards said.

When the debate turned to domestic issues, the two sparred over jobs, taxes and the president’s signature education reform plan.

On the economy, Cheney and Edwards offered starkly contrasting views of Bush’s record and painted dramatically different pictures of the domestic state of affairs.

The vice president touted job gains over the last year and said 111 million Americans paid lower income taxes thanks to Bush.

“The story, I think, is a good one,” he said.

Edwards pointed to the net loss of more than 900,000 jobs since Bush took office, along with soaring healthcare costs, a surge in poverty and the shift of U.S. jobs to foreign countries.

“Mr. Vice President, I don’t think the country can take four more years of this kind of experience,” Edwards said.

Edwards renewed Kerry’s pledges for tax breaks to help ordinary Americans pay for healthcare, college tuition and child care, along with a rollback of the Bush tax cuts for families making more than $200,000 annually.

Cheney responded by slamming Kerry’s votes in the Senate for higher taxes -- 98 of them, by his count.

“I think the Kerry-Edwards approach basically is to raise taxes and to give government more control over the lives of individual citizens,” Cheney said. “We think that’s the wrong way to go. There’s a fundamental difference of opinion here.”

By repealing Bush’s tax cuts for the highest-earning Americans, he argued, Kerry and Edwards would harm small businesses and hamper job growth.

As for the latest tax cuts that Bush signed into law this week in Iowa, Cheney again called attention to the Democrats’ absence from Washington during the campaign, saying, “Sens. Kerry and Edwards weren’t even there to vote for it when it came to final passage.”

Edwards said Kerry had voted to cut taxes -- or cosponsored bills calling for such reductions -- more than 600 times.

“There is a philosophical difference between us and them,” he said. “We are for more tax cuts for the middle class than they’re for.... But we are not for more tax cuts for multimillionaires. They are. And it is a fundamental difference in what we think needs to be done in this country.”

The two offered vastly different portrayals of the president’s Leave No Child Behind education measure designed to improve public schools. Cheney said it had already yielded positive results, boosting math and reading scores. Edwards said Bush’s stinting on funding had resulted in teacher layoffs and increases in the dropout rate for black and Latino students.

The two found a rare area of agreement on the subject of gay marriage.

Edwards said he and Kerry both believed that governments should only recognize marriage between a man and woman, though he said they supported the extension of rights -- such as allowing hospital visitations -- for gay couples in long-term relationships.

He accused Bush of using the Constitution as “a political tool” by calling for a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage. “It’s wrong,” Edwards said.

Cheney, whose daughter Mary is a lesbian, indicated that he too opposed such an amendment, repeating his words from the 2000 debate that “freedom means freedom for everybody.” He said his preference would be to leave the matter to individual states, but added, the president “sets policy for this administration, and I support the president.”

In their comments on the issue, it was Edwards rather than Cheney who made a reference to the vice president’s lesbian daughter.

After the debate, when the major TV networks had cut away for their analysis of the evening, Mary Cheney joined her mother and father and others on stage congratulating the candidates.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.