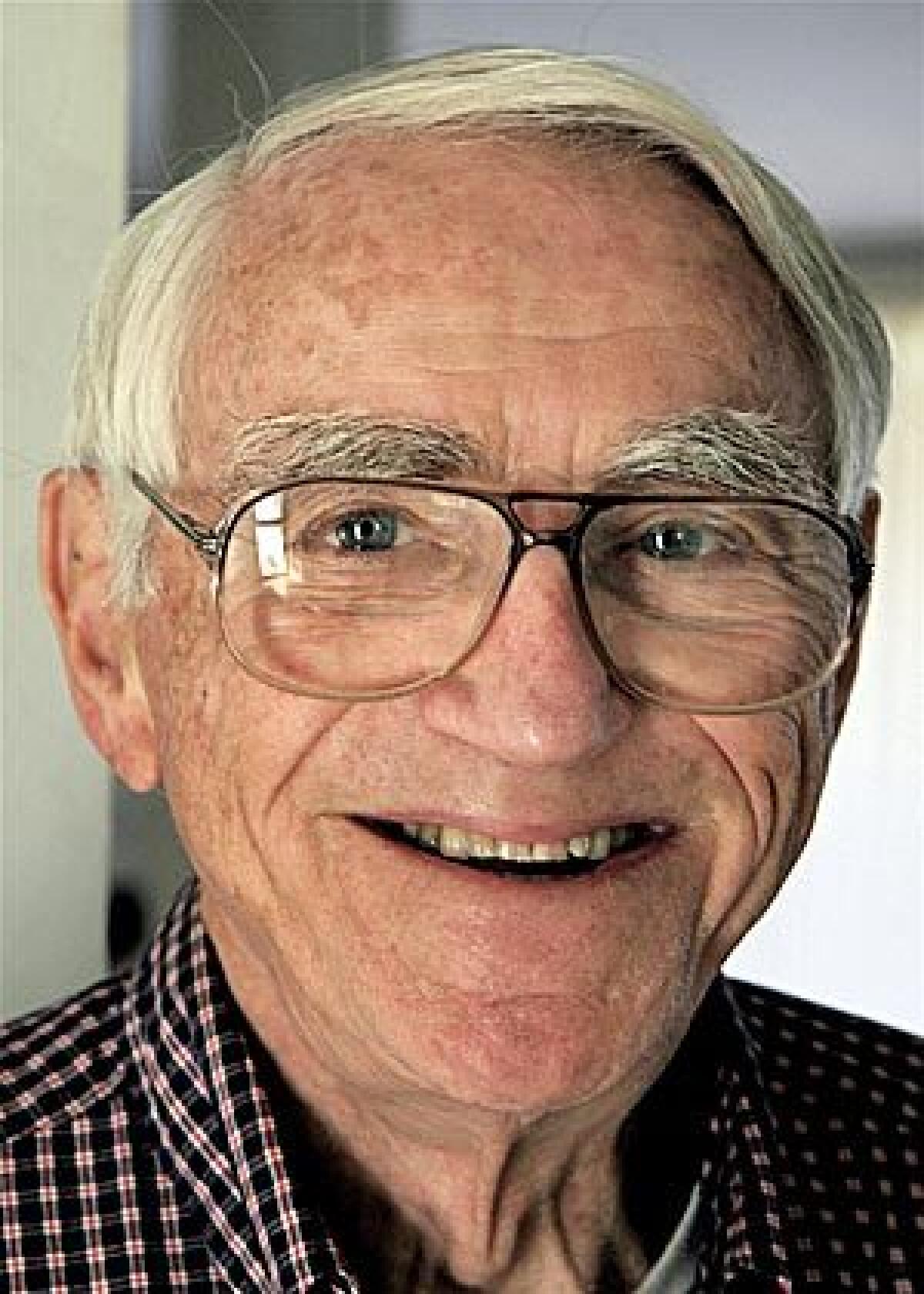

Edwin O. Guthman, 89; Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist

Edwin O. Guthman, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist and editor whose aggressive pursuit of Watergate stories during the 1970s earned him the enmity of President Nixon and the No. 3 spot on Nixon’s infamous enemies list, has died. He was 89.

Guthman died Sunday at his home in Pacific Palisades, USC announced. He had been dealing with complications of amyloidosis, a rare disorder involving the abnormal buildup of proteins in organs and tissues.

Guthman, who was also a longtime USC professor and a founding member of the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission, earned a Pulitzer early in his career for proving the innocence of a victim of McCarthyism. During a brief hiatus from journalism, he worked for Robert F. Kennedy as a Justice Department spokesman and became a Kennedy confidant.

He went on to serve as national editor of the Los Angeles Times from 1965 to 1977, a crucial period during which the newspaper expanded its journalistic mission and shed its parochial image. David Halberstam, in “The Powers That Be,” wrote that Guthman gave the paper “instant prestige” and played an important role in its transformation under Publisher Otis Chandler.

A decorated World War II veteran, Guthman was profiled in the bestselling 1998 book “The Greatest Generation,” by former NBC anchor Tom Brokaw, who wrote: “In any accounting of the good guys of American journalism, Ed Guthman is on the front page.”

Guthman was born in Seattle on Aug. 11, 1919, the son of a grocery chain executive. Guthman earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Washington in 1941 and was drafted into the Army in 1942. He fought in Italy and North Africa during World War II, earned a Purple Heart and a Silver Star and left the service with the rank of captain.

When he was interviewed by Brokaw 50 years later, Guthman credited his military experience for the disciplined approach he took to documenting the newspaper stories he would later write and edit.

Pulitzer Prize

After a brief stint at the now-defunct Seattle Star, he joined the Seattle Times in 1947. The paper assigned him to cover the Washington state Committee on Un-American Activities, one of many local bodies formed to root out Communists during the McCarthy era.

The committee had targeted a University of Washington philosophy professor named Melvin Rader, who was alleged to have attended a Communist training school in New York in 1938. Rader denied the charges but could not disprove them.

Guthman found that the committee had confiscated pages from a hotel registry that could have corroborated Rader’s contention that he had not been in New York during the weeks in question. Guthman also found receipts, library records and bank deposit slips that showed that Rader had been in and around Seattle at the time.

The stories Guthman wrote about Rader’s case saved the professor’s career, which had been in jeopardy.

Guthman’s labors paid off in 1950 when he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished reporting on national affairs.

In the next 10 years, Guthman turned his reporting talents to covering corruption in the Teamsters union and the ethics of Seattle’s Dave Beck, who was president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters from 1952 to 1957.

By 1956, the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations had begun examining corruption in the labor movement and was intensely interested in the high-living Beck. Robert Kennedy was the committee counsel.

Later that year, Guthman received a call from Clark Mollenhoff, a reporter for the Des Moines Register-Tribune (and later special counsel to President Nixon), who had been investigating Beck’s counterpart in Detroit, Jimmy Hoffa.

Mollenhoff told Guthman that a Senate committee was about to launch a broad probe into unsavory activities by top union officials and asked Guthman if he would meet with Kennedy.

When informed that the committee attorney was the brother of then-Sen. John F. Kennedy, Guthman was unimpressed and said, “That’s fine, Clark, but can you trust him?”

Despite his reservations, Guthman met Kennedy and they began to share information. In 1957, Beck was called to appear before the committee and was accused by Kennedy of illegally using $320,000 in union funds. He ultimately was convicted of embezzlement and federal tax evasion and of filing a fraudulent tax return and was sent to prison.

Kennedy years

Kennedy became attorney general in his brother’s administration in 1961 and, in one of his first acts, hired Guthman as his press secretary in the Justice Department. When Kennedy won election as U.S. senator from New York in 1964, he again asked Guthman to serve as press secretary.

In “We Band of Brothers,” Guthman’s 1971 memoir of his years with Kennedy, he made no effort to hide his affection for Kennedy, portraying him as a stalwart friend, an impassioned advocate for civil rights and a demanding boss, whose wry humor brought levity to many grim moments.

Guthman recounted the time that he was in Oxford, Miss., with other Justice Department officials in 1962 when rioting broke out on the eve of James Meredith’s enrollment as the first black student at the University of Mississippi.

A hate-filled mob armed with rocks, chunks of concrete and guns was attacking about 300 federal marshals who were under orders not to fire their pistols at the crowd. Many of the marshals were severely injured. Guthman and the other Justice Department officials watched in agony.

That night, Guthman called Kennedy in Washington to report on the situation. “How’s it going down there?” Kennedy asked, to which the aide replied, “Pretty rough. It’s getting like the Alamo.” After a pause, Kennedy quipped, “Well, you know what happened to those guys, don’t you?”

The president sent in the Army to disperse the mob, and Meredith walked up the university steps the next morning.

The exchange between Guthman and Kennedy was repeated in many published accounts of the conflict as a classic example of the camaraderie between the attorney general and his staff.

“The way I look at it, we were beleaguered and blood-spattered and he knew it and worried for our safety. And yet when I think of Oxford,” Guthman wrote, “this is what I remember first: the light remark that raised our morale and helped us through the night.”

Guthman spent five years in Kennedy’s service, leaving in 1965 after accepting an offer from Los Angeles Times Publisher Chandler to oversee the paper’s national coverage.

Three years later, on the night of the 1968 California presidential primary, Guthman spoke to Kennedy just before the candidate left his room at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles to make his victory speech. Kennedy was shot moments later by Sirhan Sirhan.

Guthman rushed to the hospital, and when he returned to The Times early the next morning, he sadly suggested that an obituary be prepared. Kennedy died the next night.

Because of his Pulitzer and his Kennedy connections, Guthman was, according to Halberstam, “the most prestigious editor” The Times had in the 1960s. He was known for his strong social conscience and his belief that reporters should strive to expose corruption. Guthman also was known as the paper’s most relentless editor, always pushing his reporters to make one more phone call to nail an important story.

Watergate

This quality was crucial in the early 1970s when the Washington Post broke the story of the Watergate break-in. In contrast to other top editors at The Times, Guthman was, Halberstam wrote, “passionate on Watergate from the start.”

The Times was one of the few papers in the country doing any Watergate stories, but it found itself always trailing the Post on reporting developments in the unfolding scandal, which arose from the discovery of a break-in by Republican operatives at the Democratic National Headquarters in the Watergate office complex in Washington. The Times’ fortunes changed in the fall of 1972, when Washington correspondent Ronald J. Ostrow learned that there might have been an eyewitness to the break-in.

One of Ostrow’s colleagues at The Times, Jack Nelson, found the witness, Alfred Baldwin, and secured an exclusive interview. Although Times lawyers warned of the enormous legal risks and the government was pressuring the paper to drop the story, Guthman talked Times Editor William F. Thomas into running the piece. It became one of the most important stories about the entire episode because, in Halberstam’s view, it “brought Watergate right to the heart of the Nixon reelection campaign in a more dramatic way than any other story so far.”

In 1973, the public learned that Nixon had kept a list of political enemies. On a prime list of 20 enemies, Guthman was No. 3, after a Democratic fundraiser and a high-ranking AFL-CIO official.

The list was released by former presidential counsel John W. Dean III, who said it had originated in the office of former White House special counsel Charles W. Colson. It described Guthman as “a highly sophisticated hatchet man against us in ’68.” The memo went on to say that it was time to “give him the message,” apparently an allusion to government harassment.

Guthman said that he never received any “message” and that Colson’s memo was rife with misstatements, including a reference to him as the paper’s managing editor. It also erred in saying that he had been involved in Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign.

Kenneth Reich, a former Times reporter who knew Guthman for many years, said his former colleague “was very proud to have made the enemies list.”

But Guthman was also outraged to be on it. He said any law-abiding American citizen would resent being targeted for retribution from his government. “I resent it even more so because it was done by people who seem to have had no respect for our Constitution or our laws,” he said in 1973. Reich died in June.

Guthman, who at one time was considered a strong contender for editor of The Times, left the paper in 1977 after a dispute with other top editors. He spent the next decade at the Philadelphia Inquirer as editorial and Op-Ed editor. After retiring from the Inquirer in 1987, he joined the faculty of USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and taught journalism for the next 20 years.

L.A. ethics panel

In 1993, Guthman was named to a federal panel reviewing the government’s role in the deadly raid in April of that year on the Branch Davidian compound near Waco, Texas, that claimed the lives of four government agents and about 80 followers of cult leader David Koresh.

The panel concluded that top officials of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, the federal agency that conducted the initial action, had been negligent in overseeing the operation.

From 1991 to 1998 Guthman served on Los Angeles’ first Ethics Commission, a watchdog agency formed after a conflict-of-interest investigation of Mayor Tom Bradley.

Guthman was a strong backer of Benjamin Bycel, the controversial founding executive director of the ethics panel who was abruptly fired in 1996 after criticism that he had been too aggressive in his enforcement of anti-corruption rules.

Guthman, who served a term as commission president, also helped draft new laws regulating lobbyists and guided its probes of campaign money laundering in local elections. One of the commission’s investigations led to the conviction of a former city councilman.

Bill Boyarsky, a former commission member and former Times political writer and columnist, said Guthman “set a perfect example of what a commissioner should do. . . . Ed believed in the political process. He liked politicians.”

“Working with the late City Council President John Ferraro, he worked out rules and regulations that still govern the commission. But even though Ed liked politicians, he did not hesitate to crack down on them when they violated the law.”

In late 2007, Guthman was honored by the Los Angeles City Council for his wide-ranging achievements. He also retired from USC last year.

Guthman’s wife, JoAnn, died in 1990. He is survived by sons Lester, Edwin H., and Gary; a daughter, Diane; and five grandchildren.

Services will be held at 1 p.m. Friday at Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary, 6001 W. Centinela Blvd., Los Angeles. Memorial donations may be made to the Edwin O. and JoAnn Guthman Endowed Scholarship for Investigative Reporting at the USC Annenberg School for Communication, 3502 Watt Way, Los Angeles, CA 90089.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.