In boot camp, Marine recruits learn to battle suicide

SAN DIEGO — The basic rule for Marine boot camp is simple: Keep your mouth shut and mind your own business.

But it’s different when the subject is suicide.

Drill instructors encourage recruits to share their feelings in “guided discussions” and tell them to watch out for, and promptly report, warning signs in their buddies.

The suicide rate in the active-duty Marine Corps was 16.5 per 100,000 in 2007 -- below both the active-duty Army and a similar demographic in the civilian population. But it had jumped from 12.9 in 2006.

In the first six months of this year, 25 Marines committed suicide, the most in that period of time since such records began to be kept several years ago. If that trend persists, 2008 could prove the worst year for Marine suicides since at least the beginning of the war in Afghanistan.

“Current prevention strategies are being evaluated and developed to respond to this increase and the ongoing wartime demands and associated stressors confronting Marines,” said Navy Cmdr. Aaron Werbel, manager of the Marine Corps’ suicide prevention program.

“Training is being conducted for Marines, leaders, counselors, chaplains, family members and frontline installation staff who have routine contact with young Marines,” he said.

In April, representatives of all the military branches attended a weeklong conference here to hear from civilian experts and discuss ways to improve prevention programs.

The Marine Corps provides advanced training in suicide prevention for chaplains, corpsmen, mental health specialists and career counselors.

But the first line of defense against suicide remains the young Marine who is in the best position to notice changes in a buddy. Learning how to recognize warning signs is a key element of training, which begins at boot camp and is reinforced later, particularly as Marines prepare to deploy.

On a recent Sunday afternoon, 72 recruits sat on the floor of their barracks listening to a senior drill instructor talk about suicide. Two days earlier they had heard a lecture from a chaplain about how to spot suicidal tendencies.

Now the drill instructor was checking to see what they remembered from the lecture and encouraging them to talk about their experiences. When he asked how many had known someone who committed or attempted suicide, nearly a third of them raised their hands.

For the session, Staff Sgt. Nicholas Romer dropped the gruff, demanding voice of the classic drill instructor. Now he was an older brother. By prearrangement, two recruits role-played, with one acting as the would-be suicide, the other his shipmate. Then Romer asked recruits to share their views about suicide.

“This recruit knows that in the Bible it says ‘Thou shall not kill,’ and that includes yourself,” said one recruit. “If the last thing you do is to commit a sin, you’re going to hell.”

“As a Buddhist, this recruit knows that life is a gift from God,” another said.

Some of the young men expressed anger and many expressed sadness.

“The people who die like that are the worst . . . people you’ll ever meet,” a recruit told Romer. “All you’re doing is taking your burden and throwing it on other people’s burdens.”

One recruit said that his grandfather had committed suicide after his grandmother died of cancer. Another said he had come home and found his mother hanging. Several said they had had to wrestle guns and knives away from friends.

Romer listened to them and provided perspective: “There’s nothing here that is so bad it’s worth taking your life.”

He also reinforced the chaplain’s message that it’s the duty of the individual Marine to intervene when a buddy starts showing possible signs that he is thinking of suicide: giving away his possessions, acting unusually listless, withdrawing from contact, getting angry for no reason, showing a preoccupation with death.

Judging from the risk factors, Marine enlistees are prime candidates for suicide. They are young males far from home and family support. They are being stressed to their mental and physical limits. Their coping skills are still maturing.

Once recruits graduate from boot camp, the risk factors increase with easy access to weapons, the probability of repeated deployments to Iraq, the prospect of Dear John letters from girlfriends who grow tired of waiting.

Recruits are told that if a Marine exhibits warning signs, it’s their duty to inform a sergeant, a chaplain, a corpsman: somebody in the chain of command. If nothing else, they are told, take away the Marine’s weapons.

“Every year we lose about a rifle platoon worth of Marines to suicide,” Navy chaplain Lt. Wayne Tomasek told the recruits in the lecture that preceded their discussion with Romer.

“There is no tomorrow. Tomorrow will be too late,” Tomasek said. “Intervene now. Don’t waste time. Are you up for that challenge?”

“Yes, sir!” the recruits shouted back.

The majority of Marine suicides occur stateside.

Of the 25 who killed themselves this year, eight had never deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, 15 had returned from a war-zone deployment and two committed suicide in Iraq.

In 2007, of the 33 Marines listed as suicides, most were under 24. Two-thirds used firearms. The others hanged themselves or took poison.

Werbel, manager of the suicide prevention program, has established a website to provide information and updates on suicide prevention classes and videos. He travels from base to base lecturing commanders on the need to continually reinforce the lessons that recruits learn in boot camp.

At the Marine Corps recruit depots, every group of recruits gets a lecture from the chaplain, a discussion with a drill instructor and a test. Instructors are ordered to refer any recruit who looks shaky to mental health specialists on base.

In his discussion, Romer emphasized group loyalty.

“The guys you’ll deploy with are not just your friends. They’re your brothers.”

Moments later, before the recruits hurried off to the chow hall, 19-year-old Christopher Martinez of Keller, Texas, discussed what the effect on the group would be if one of them committed suicide.

“It would be devastating to all of us,” Martinez said. “We’ve only been together a few weeks, but this group has jelled into something special. We’re going to be Marines.”

--

--

On latimes.com

One man’s story

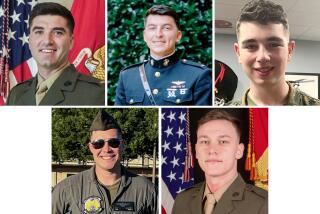

Colleagues saw few warning signs before 20-year-old Marine committed suicide in Iraq, a military investigation shows.

latimes.com/california

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.