Transplant monitor lax in oversight

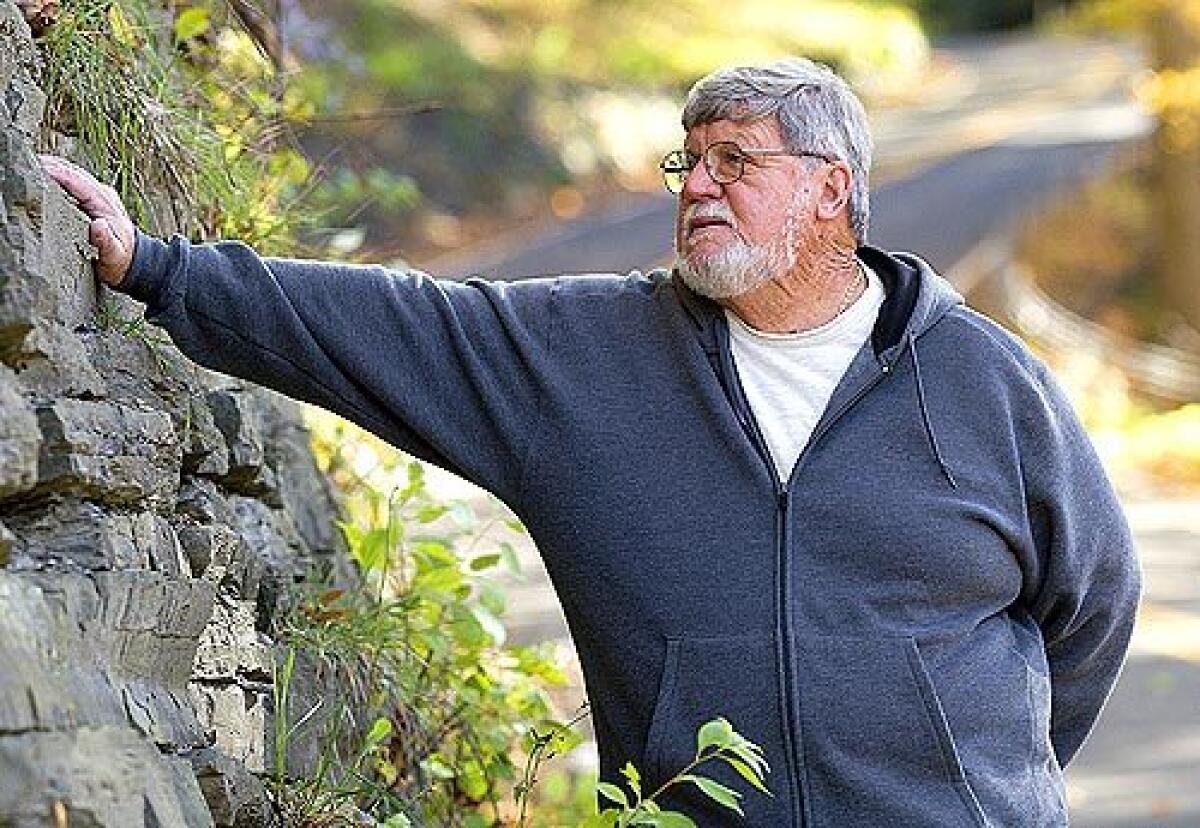

Thomas Pierce, 69, knew nothing of problems at Shands at the University of Florida before his wifes surgery in October 2003. In fact, UNOS knew that Shands kidney patients had been dying at higher-than-expected rates for several years. After she received her new kidney, Jacqueline Pierce, 60, developed a rare, and ultimately fatal, complication. They said, Dont worry, we never lose them,. Thomas Pierce said.

The little-known organization that oversees the nation’s organ transplant system often fails to detect or decisively fix problems at derelict hospitals — even when patients are dying at excessive rates, a Times investigation has found.

When it does act, the United Network for Organ Sharing routinely keeps findings of its investigations secret, leaving patients and their families unaware of the potential risks, interviews and confidential records show.

“It seems like UNOS is often a day late and a dollar short,” said Dr. Mark Fox, associate director of the Oklahoma Bioethics Center and former chairman of the UNOS ethics committee. “Most people are kind of shaking their heads and saying, ‘Who’s minding the store?’ ”

In the past year, UNOS has been blindsided by life-threatening lapses at centers it oversees. After The Times uncovered such problems at two California programs, both abruptly closed.

UNOS’ failures in those cases are part of a larger national pattern of uneven and often weak oversight. At times, the group appears more intent on protecting hospitals than patients themselves, the newspaper has found.

Since 1986, the federal government has contracted with UNOS to oversee everything from how organs are harvested to where they end up.

It is a daunting job. The competition for scarce organs is growing. And because the stakes are so high — life or death for patients, prestige and millions of dollars for hospitals — the temptations for transplant centers to bend or break the rules are ever-present.

As the overall arbiter of safety and fairness in the country’s transplant system, UNOS has the power to issue public rebukes and urge the government to close troubled programs.

But it has shown itself a reluctant enforcer, according to a Times review of confidential UNOS documents and interviews with dozens of past and present board members, transplant doctors, patients and others.

UNOS has never recommended that the government close an active transplant program.

Since 2000, the nonprofit organization has considered revoking the “good standing” of at least 15 transplant centers — its most serious public sanction and a potentially embarrassing blow to a hospital’s reputation. But it has followed through just once — in March. In that case, St. Vincent Medical Center in Los Angeles had arranged for a liver transplant candidate to jump ahead of dozens of others in line for an organ.

Even after programs log high death rates, years sometimes pass before UNOS takes meaningful action.

UNOS, for instance, was aware by 2002 of potentially lethal problems in the kidney program at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center in Las Vegas, but four years passed before the regulator performed its own inspection. In the meantime, patients were dying at rates UNOS knew to be unacceptably high.

UNOS often backs down after being challenged — or even defied — by medical centers it is supposed to regulate.

Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee refused UNOS’ repeated calls to shut down its lung program in 2004. It wasn’t performing any transplants, yet kept children on its waiting list, effectively putting them out of the running for critical surgeries. UNOS threatened its most serious public sanction. The final punishment: confidential probation.

UNOS officials have missed obvious red flags, including troubling transplant center statistics available on its own website.

UNOS statistics showed that Kaiser Permanente’s new kidney program in San Francisco was in serious trouble last year: Twice as many patients had died awaiting transplants as had received them. Other California programs showed the opposite pattern: Twice as many people received transplants as died.

UNOS didn’t launch an investigation until May, after The Times detailed the program’s failings. The program closed that same month.

Celia Scull, 61, said she is angry that UNOS didn’t know enough to step in earlier. “I find that appalling,” said Scull, a Kaiser transplant candidate from Sacramento who now is transferring to another center. “Does it upset me? You bet it does.”

Similarly, UNOS was unaware of the severity of problems within the liver program at UCI Medical Center in Orange. With no full-time surgeon to do transplants for more than a year, UCI turned down scores of organs that might have saved patients on the waiting list. The day the problems were reported in The Times in November, the program closed.

UNOS leaders say they have been embarrassed to learn about serious failings of their organization in the paper.

Executive Director Walter Graham described the recent troubles at California centers as a “watershed” for UNOS. The problems were “hurting public trust,” Graham said. “There has been this escalating desire to stop that. The sense of outrage has grown in the transplant community.”

Within the last year, the UNOS board has voted to make some changes, such as publicizing the names of centers on probation and speeding up some investigations. Generally, however, resolving matters amicably serves patients better in the long run than issuing black marks, UNOS officials said.

Such collegiality is built into UNOS’ very structure — and that’s the problem, some critics say. UNOS isn’t just a regulator; it is a membership organization, run mostly by transplant professionals. Centers, in effect, oversee one another.

“UNOS really can’t police itself,” said Dr. John J. Fung, director of the Cleveland Clinic’s transplant center and a former UNOS board member. “Everybody is beholden.”

“It’s kind of like the fox guarding the chicken house,” agreed U.S. Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, who has ordered an investigation of the country’s transplant oversight system by the Government Accountability Office.

“These folks have a short period of time to get their house in order or else they’re begging greater government interference and enforcement.”

Breaking the rules

A few years ago, Temple University Medical Center found a way to speed up its patients’ waits for heart transplants.It reported some patients to be sicker than they were, according to records and interviews, allowing them to jump ahead of patients at other hospitals on a UNOS waiting list.

The hospital did this repeatedly — over four years.

Patients at other hospitals, some of whom were unfairly bumped down the list, had no way of knowing what happened. In fact, the story has never been publicly disclosed.

UNOS knew what was going on, though. In 1999, records show, a UNOS inspection found that the hospital was unable to prove that at least 13 of its patients were sick enough to be classified as “Status 1A,” meaning they were on the verge of death and entitled to priority. Temple officials said it was a mistake — it had misinterpreted the rules, according to a confidential UNOS summary of the Temple case.

UNOS closed the matter.

In the months that followed, however, UNOS reviewers determined that Temple had inflated the conditions of 12 more patients. During a January 2001 meeting with UNOS officials, Temple proposed a compromise: It would have its Status 1A listings reviewed in advance by a UNOS panel. In return, the oversight group agreed to hold off on discipline for a year.

In 2002, Temple broke the rules again, misclassifying a patient as near death. After UNOS reviewers rejected the assessment, the hospital proceeded with the transplant anyway.

The hospital’s cross-town competitor was incensed.

“If there’s a sense that one place isn’t playing by the rules, and you play by the rules, then your poor patients aren’t going to get a fair shake,” Dr. Michael Acker, head of cardiac transplantation at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, said in a recent interview.

In a July 2002 inspection, UNOS found 64 more cases in which the patients’ urgent conditions “could not be confirmed with the facts” in their medical records, the UNOS summary said.

That October, UNOS again compromised with Temple, agreeing not to revoke the hospital’s “good standing” if Temple promised to change its ways.

The following month, its board of directors placed Temple on confidential probation. Temple completed its probation in January 2006.

“Our transplant program today has been infused with new leadership and improved processes that continue to meet or exceed all recognized industry standards,” Temple said in a written statement to The Times.

UNOS’ timid response to Temple is not an isolated example.

In 2001, UNOS became aware that the pediatric lung transplant program at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin was performing too few surgeries and had a high death rate, according to a confidential UNOS summary.

UNOS requires hospitals to perform transplants at regular intervals to ensure that patients aren’t left waiting in a program that isn’t doing them. Separately, Medicare officials set a far higher threshold to make sure a hospital is doing enough procedures to remain proficient.

UNOS also flags programs with inordinate rates of death and organ failure within a year of surgery, based on statistical reports it receives every six months. These data, prepared by a separate government contractor, take into account the condition of patients and organs at individual centers.

In mid-2002, UNOS conducted an inspection at Children’s, prompting the hospital to submit a plan to fix its problems.

About a year and a half later, however, UNOS found the hospital’s improvements inadequate. A UNOS disciplinary panel recommended that the program voluntarily suspend itself. Children’s refused. The panel asked again in May 2004 and once more in October, with the same result.

Finally, in July 2005, UNOS’ disciplinary panel unanimously recommended revoking the program’s “good standing,” the summary shows.

Two months later, the panel retreated, advocating confidential probation — a decision ultimately approved by the full UNOS board.

The reversal was not explained in the document.

In a statement to The Times, Children’s defended the program’s low numbers, saying the nation’s 17 pediatric lung centers performed just 54 transplants last year and that the program has “dedicated significant resources to growing and maintaining expertise.”

UNOS officials declined to discuss any of its confidential reviews but suggested the organization is now more aggressive.

“There’s no sense in going through that history,” said Dr. Francis L. Delmonico, who was UNOS president until June 30. UNOS, he said, has changed. “What may have been in the past — that’s a different day.”

Judging from the numbers alone, Children’s hasn’t changed much. As of Friday, it had performed just one transplant in nearly four years.

Six children remain on its waiting list.

‘Not a police force’

Ask current and former UNOS leaders about their enforcement record and they often respond by saying what their organization is not.“UNOS is not the FBI,” said board member Dr. Gabriel Danovitch, medical director of UCLA Medical Center’s kidney and pancreas transplant program. “It’s not a police force.”

“It was never really designed as an enforcement agency,” said Dr. Dale Distant, a former board member and transplant chief at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in New York.

In fact, UNOS evolved from a group of transplant professionals who created a computer system in 1977 to ensure that kidneys were fairly distributed.

Few anticipated that by 2005, the nation’s 259 transplant centers would perform as many as 28,000 heart, lung, liver, pancreas, kidney and other organ transplants.

Today, UNOS’ 276 employees are housed in a sleek, $17.5-million glass complex in Richmond, Va., with an elaborate memorial garden for donors. Each year, it receives $2 million from the federal government and much more — $23 million — in fees from transplant centers.

In 2000, the government gave UNOS more teeth, but the organization prefers to privately nudge centers into compliance.

If all else fails, officials say, they pressure programs to shut themselves down. They say that such pressure has led to the closure — at least temporarily — of more than 80 transplant programs since 2000.

UNOS refused, however, to name the programs or describe the circumstances.

A top federal health official said the government is satisfied with its contractor’s performance.

“It ought to be reassuring to people that the vast, vast majority of what’s going on is according to good rules that are followed very carefully,” said Dr. James Burdick, director of the division of transplantation within the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Burdick is a past president of UNOS.

Members of UNOS’ board and committees are rotating volunteers — mostly doctors and other transplant professionals who sandwich UNOS duties between other obligations. Some members complain that the group needs more money to handle its growing enforcement needs.

It’s a relatively small world in which colleagues — even friends — end up in judgment of one another.

For example, UNOS documents show that at least three of the centers the group is slated to inspect in coming months employ current board members: Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Ohio State University Medical Center in Columbus and Christus Santa Rosa Health Care in San Antonio.

Programs at all three have had worse-than-expected surgical outcomes, such as high rates of organ failure or death, based on national statistics.

UNOS says board members must abstain from votes affecting their program or others in their regions. Also, programs are referred to by code during initial inquiries so as not to prejudice opinion. But when discipline is recommended to the full 42-member UNOS board for final approval, the names are revealed.

Judith Braslow, who oversaw the federal government’s division of transplantation from 1990 to 1998, said that although UNOS generally does a good job, it is difficult for the group to be “completely objective because they essentially wear two hats.”

“In their capacity as the government contractor, they have responsibility to keep the public informed. In their capacity as a membership organization, they have responsibility and loyalty to their members,” she said.

“Those two roles are really in conflict in terms of the policing function.”

A deadly complication

Thomas Pierce, 69, knew nothing of problems at Shands at the University of Florida before his wife’s surgery in October 2003. Staffers boasted that the program ranked among “the best there was,” Pierce recalled.In fact, UNOS knew that Shands’ kidney patients had been dying at higher-than-expected rates for several years.

After she received her new kidney, Jacqueline Pierce, 60, developed a hernia at the site of her incision and her small bowel became trapped inside of it, a rare complication.

“They said, ‘Don’t worry, we never lose them,’ ” Thomas Pierce said. “Then, all of a sudden, I walked in there one day and they said, ‘Your wife is going to die.’ ”

Dr. Peter Stock, a UC San Francisco transplant surgeon who reviewed Jacqueline Pierce’s records for The Times, said that he could not determine whether her death was avoidable.

Pierce just wishes he had known of Shands’ record before he took his wife to the hospital: Statistics monitored by UNOS showed that the hospital had a higher-than-expected death rate dating to 1998. Among patients who received transplants between January 2000 and June 2002, for example, nearly twice as many as expected died within a year. (The statistics cannot be matched to individual patients.)

Today, patient survival has improved at Shands and meets UNOS’ standards. Transplant director Dr. Richard Howard said the program has changed the way it selects patients and organs, as well as medication regimens. But Howard, who served on the UNOS board until June and has been at Shands since 1979, said he doesn’t recall UNOS’ being involved in those reforms.

The center’s improvement means nothing to Pierce.

“I can remember driving home from Shands after my wife had died, thinking my life is done,” he said. “My wife was my whole life.”

No consistent backstop

As UNOS has stuck to its slow and silent ways in recent years, other agencies occasionally have stepped in to protect patients or punish wrongdoers.In 2002, for instance, the federal government was forced to sue UNOS — its own contractor — to get information about allegedly improper conduct by three liver transplant programs in Chicago. UNOS argued the information was confidential.

A federal judge sided with the government, saying that the material could show “whether some [patients] have been permitted to barge to the head of the line.”

The hospitals later agreed to settle federal claims alleging that they had fraudulently diagnosed and hospitalized certain patients to make them eligible for transplants sooner.

More recently, the UNOS board took no public action against three transplant centers in New York, even though state officials found problems egregious enough to levy fines.

In 2004, for example, regulators fined Strong Memorial Hospital in Rochester $20,000 for failing to document why the liver transplant program was using less-than-ideal organs and not telling patients about the risks. At least two patients suffered organ failure and needed new transplants.

In a statement at the time, Dr. Antonia C. Novello, New York’s health commissioner, said she was “troubled by the gaps in the hospital’s quality assurance system” and its failure to “correct significant breakdowns in its liver transplant program.”

It is not clear whether UNOS was aware of these problems. But it had considered revoking Strong’s “good standing” the previous year — in that case, for exaggerating the conditions of its heart and liver patients. It ultimately didn’t do so, records show.

Despite these cases, UNOS generally has no consistent backstop if it fails to do its job.

The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services oversees the nation’s federally funded transplant centers — a significant part of the system. The two organizations’ regulatory duties overlap somewhat. Both, for instance, are supposed to keep an eye on death rates. But they rarely have shared information and have different standards for flagging errant programs.

One characteristic they often share: failing to act decisively.

According to a Times investigation in June, the Medicare agency had neglected to pull funding from nearly 50 programs that did not meet its minimum standards in recent years.

A high rate of failure

Among the programs given years of leeway by UNOS, the kidney transplant center at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center in Las Vegas stands out.Sunrise, just a few minutes’ drive from the city’s famed Strip, first heard of the regulator’s concerns in 2002, a hospital official said. UNOS sent a matter-of-fact letter noting the center’s high incidence of organ failure after transplants and asking for more information.

UNOS knew that between July 1998 and June 2000, 21% of the transplanted kidneys failed within a year, more than twice the expected rate of 9%. The program’s survival rate was low as well: 88% for patients one year after surgery, compared with an expected 95%, given its patients’ conditions. Over the next four years, patients continued to die at excessive rates. But UNOS appeared locked in a slow procedural dance, based on its internal records.

It recommended an inspection in January 2003, then put it “on hold” so that Sunrise could bring in its own outside reviewer, internal UNOS documents show.

That review found that program officials were “not as stringent as we should have been” in weeding out patients who were not good transplant candidates, in particular older patients with heart disease, Dr. Scott A. Slavis, Sunrise’s medical director and sole surgeon, said earlier this year. In response, the program changed its criteria for new patients, Slavis said.

But too many patients continued to die.

The 2003 reforms, said Amy Stevens, system vice president for Sunrise Health, “didn’t close the gap enough between expected and actual deaths.”

In April 2005, a UNOS panel recommended that the group do its own inspection within “the next three to six months,” records show. Nearly a year passed before UNOS reviewers finally went to Sunrise. All the while, Sunrise remained a member of UNOS “in good standing.”

“We never heard anything about that,” said Janis Alamo, referring to Sunrise’s death rates. “We didn’t know any of that.”

Alamo’s husband, Delfino, was on Sunrise’s kidney waiting list for more than two years before he transferred to the city’s other program because, she said, he found staff members difficult.

In fact, as the UNOS inquiry dragged on, Sunrise’s survival rates remained among the lowest in the country in 10 consecutive statistical reports, updated every six months. No other transplant program had a lower-than-expected rate for so long.

About 15 more patients died than expected within a year of their surgeries between 2000 and 2004, according to these statistics. It is an extreme number for a program performing about 30 surgeries a year.

Stevens said the hospital is addressing UNOS’ concerns. It is recruiting a second transplant surgeon and has filed a detailed plan of correction.

“We are committed to building this program,” she said.

Stevens said the program never directly told patients about the problems but provided them with website addresses that would allow them to view outcome statistics.

Patients and transplant specialists say such statistics are often incomprehensible to the layperson. Monitoring the numbers — and stepping in where necessary — is UNOS’ job.

“I think they’ve done a disservice to the patients at that program that are waiting,” said the Cleveland Clinic’s Fung when told of UNOS’ handling of the Sunrise situation.

UNOS officials declined to comment specifically on Sunrise. Dr. Sue V. McDiarmid, UNOS’ president, said it is better for the group’s investigations to be thorough than quick.

“If you come down too fast and hurriedly and potentially wrongly, you can do a good deal of harm to patients on the waiting list,” said McDiarmid, who also is a pediatric liver specialist at UCLA Medical Center.

For the last four years, the dozens of patients on Sunrise’s waiting list have been none the wiser.

charles.ornstein@latimes.com

tracy.weber@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.