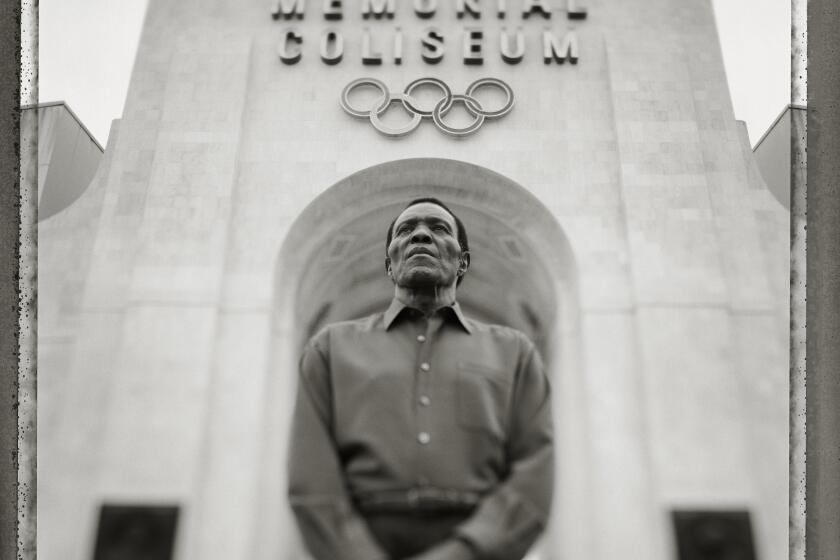

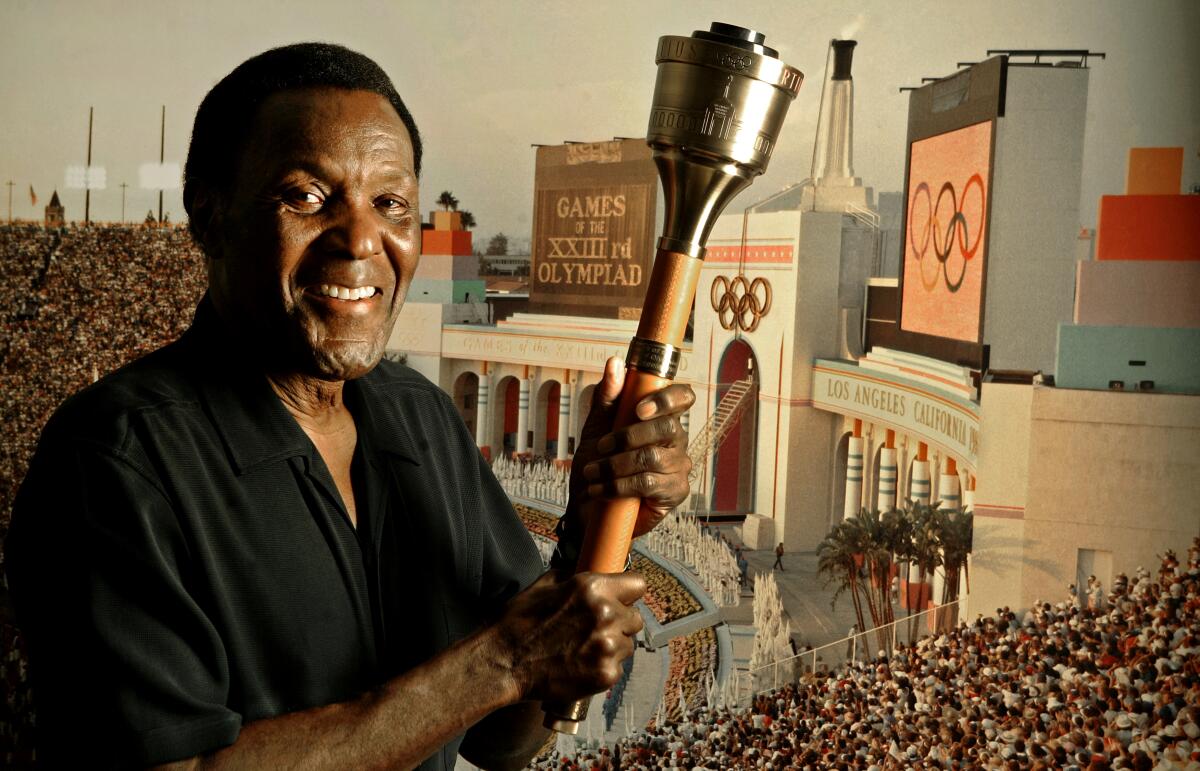

Olympic gold medalist Rafer Johnson, who helped bring Summer Games to L.A., dies at 86

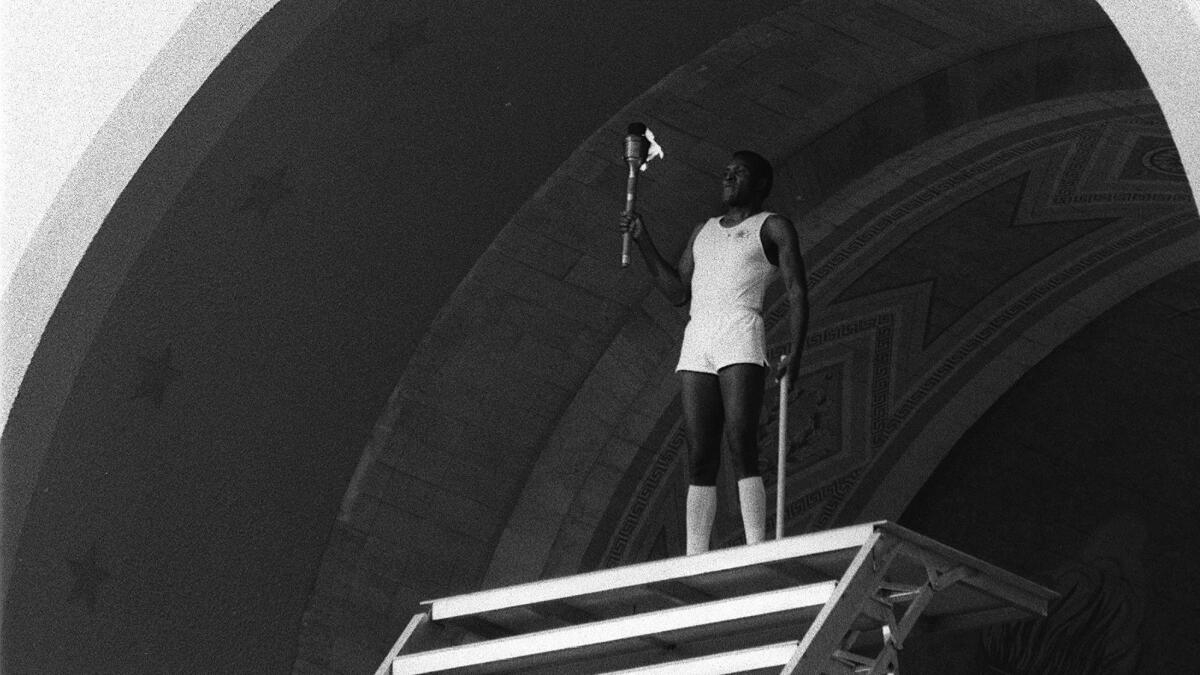

As the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles neared, city leaders knew they needed to start strong. Many doubted the city could pull off such a global event, and a weak or botched opening ceremony might prove them right.

For the key role of lighting the Olympic flame, organizers chose Rafer Johnson, winner of the 1960 Olympic decathlon gold medal and one of the city’s most treasured athletes. But in preparation for the opening ceremony, Johnson discovered a problem.

Plans called for Johnson to carry the Olympic torch up the progressively steeper stairs of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, and then up an even steeper — and shaky — set of steps to a platform where he was to turn to the crowd, flaming torch in hand, and open the Games by igniting a gas jet. But the top step was so narrow, and the riser so wobbly, that Johnson asked for a handhold to be installed.

The producer of the ceremony protested, saying a handhold would ruin photos of the moment.

“What would be a worse picture,” Johnson replied, “me holding on to something or me falling headfirst down to the floor of the Coliseum?”

Johnson got the handhold, and his lighting of the Olympic flame proved to be an iconic moment in a widely praised ceremony.

It was a fulfilling role for Johnson, a man whose legacy was interwoven with Los Angeles’ history, beginning with his performances as a world-class athlete at UCLA and punctuated by the night in 1968 when he helped disarm Robert F. Kennedy’s assassin at the Ambassador Hotel.

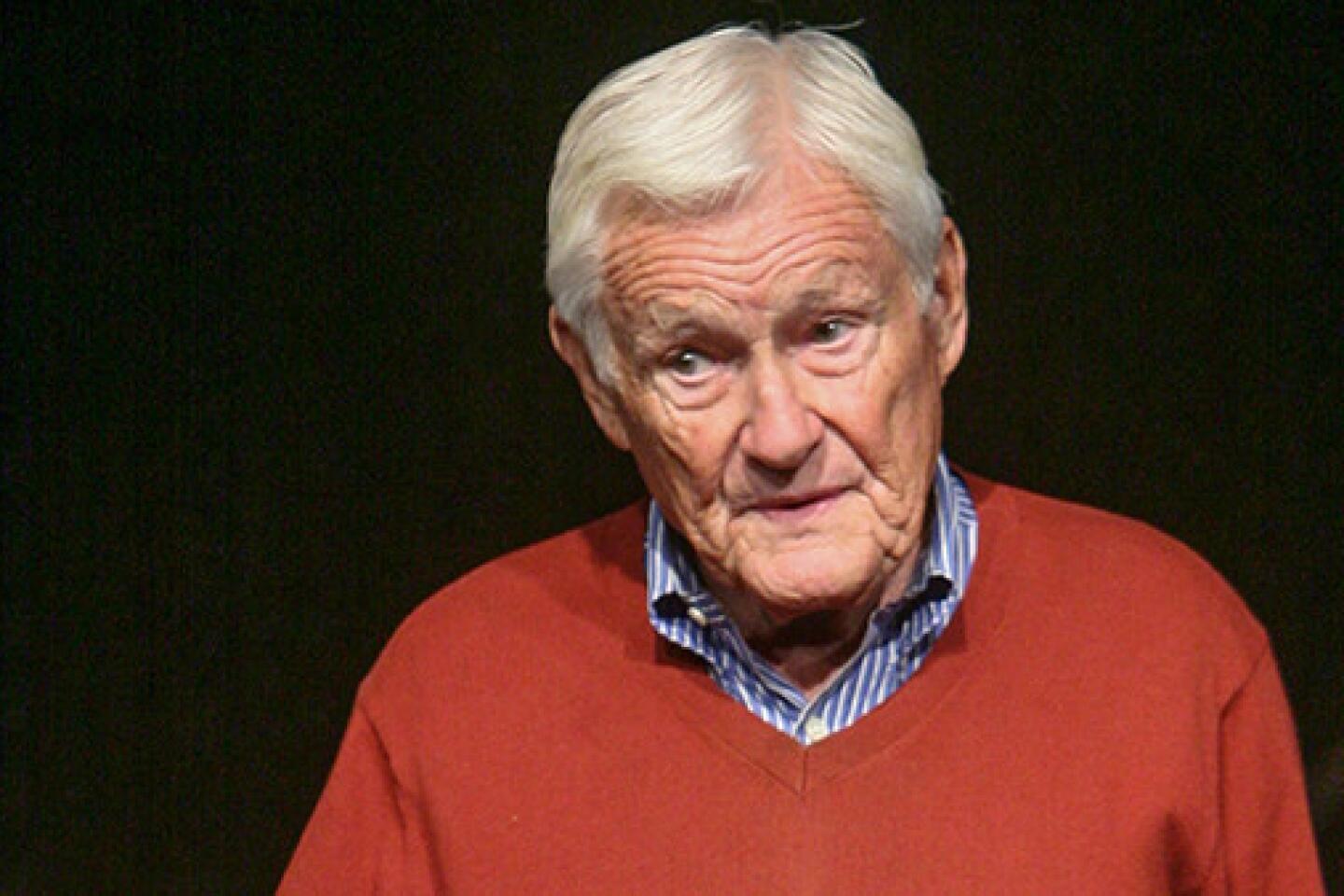

Forever a civic booster in the metropolis where he lived, Johnson died Wednesday at his home in Sherman Oaks. The Olympian’s death was confirmed by his family. He was 86.

The son of Texas farmworkers who moved to California when he was young, Johnson rose to become the World’s Greatest Athlete, the unofficial title bestowed on the winner of the Olympic decathlon at a time when track and field stars received the adulation that today is bestowed on the best of the NFL and NBA.

At the 1960 Rome Olympics, Johnson was the U.S. team’s flag bearer, the first Black American so honored. His decathlon battle that year with C.K. Yang — his training partner at UCLA — ranks among the classic moments of Olympics history.

In an eventful life, Johnson broke racial barriers, played an unexpected role in the international relations of the Cold War and immersed himself in the turbulent politics of the 1960s. To help disabled children, Johnson co-founded the California Special Olympics in 1969 and served as its president for 10 years.

In contrast to the anything-to-win attitudes often found in sports today, the deeply religious Johnson was always a vocal advocate for fair play and good sportsmanship. He eschewed drugs and alcohol and, in track races, refused even to try to anticipate the starter’s gun, believing that it was a form of cheating.

“It seems funny to say winning is not all-important — I always want to win, and no one likes to lose,” he once said. “But when you start out on the field, everyone is equal. That is the important idea.”

Rafer Johnson is a man and an athlete whose life both literally and figuratively lit a flame.

Rafer Lewis Johnson was born during the Depression, on Aug. 18, 1934, in Hillsboro, Texas, the second of six children born to Lewis Johnson, a cotton picker and farm handyman, and Alma Gibson Johnson. After a brief move to Oklahoma, the family returned to Texas when Johnson was 3 and settled in a Dallas home with no electricity or indoor plumbing.

When he was 9, Johnson’s parents, in search of a fresh start and better opportunities for their children, moved to the San Joaquin Valley town of Kingsburg, where most of the residents were of Swedish descent. The Johnsons were the only Black family.

Johnson and his siblings would join his parents picking cotton after school, on weekends, holidays and all summer. Johnson believed the hard work not only made him strong, but gave him discipline that would later help make him a successful athlete. In his 1998 autobiography, he wrote, “Thinking about picking cotton brings tears to my eyes to this day, just from remembering how hard my parents had to toil to earn a meager living.”

He recalled his father as a “kind, hard-working family man” when he was sober, but a “hell-raising drunk” who beat his wife when he’d been drinking. It was a specter that would loom over much of Johnson’s life.

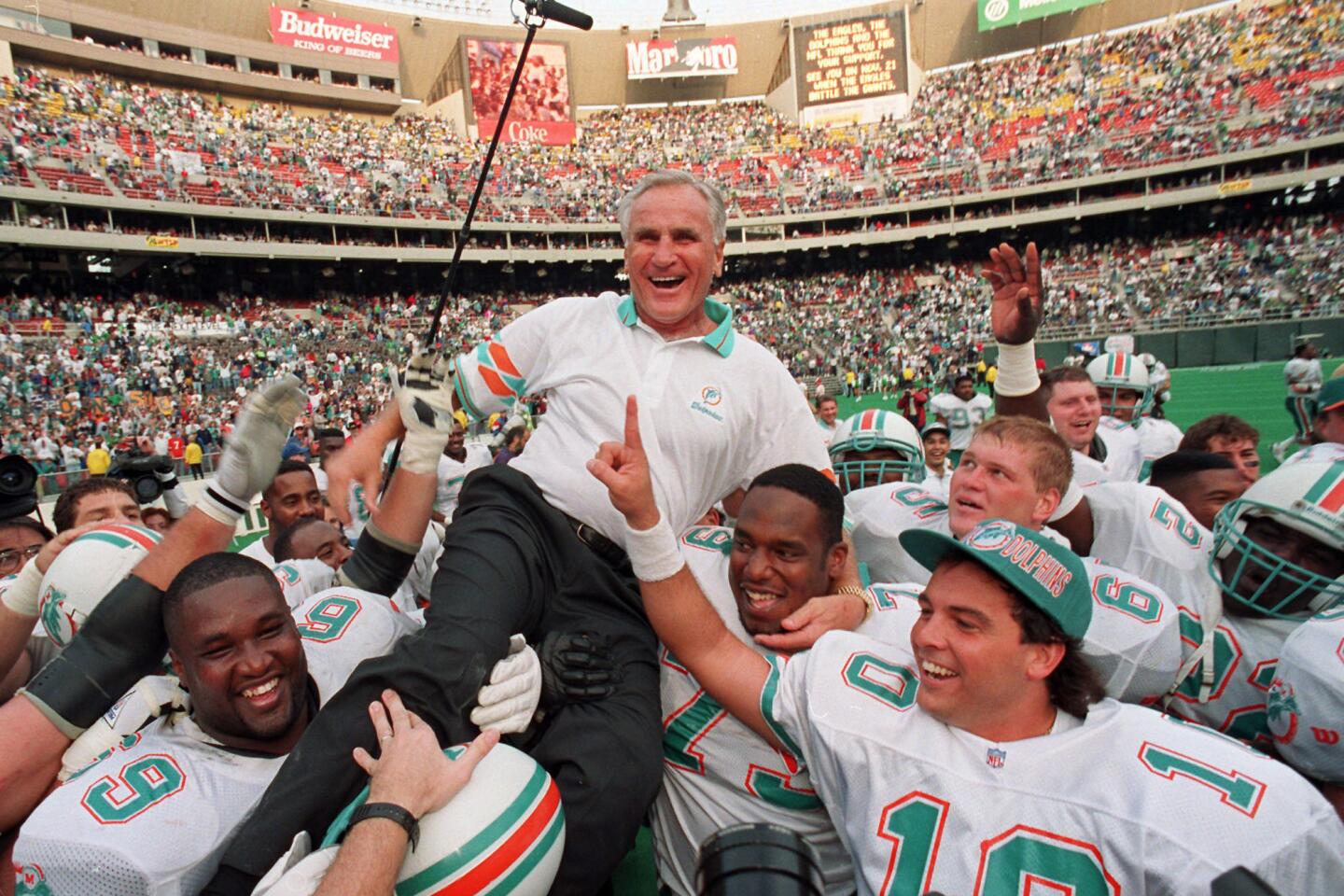

Johnson remembered his years in Kingsburg fondly, saying it was like a “Frank Capra movie.” Still, there were dangers. Johnson once saved his brother Jimmy from drowning at a local swimming hole. Jimmy Johnson would later go on to play for the San Francisco 49ers and be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Johnson was a four-sport star in high school, lettering in football, baseball, basketball and, his favorite, track and field. “There was something pure and innocent about the sport: You ran, you jumped, you threw things, just as young men had done since the dawn of civilization,” he wrote in his autobiography.

For college, Johnson chose UCLA, in part because its alumni included Jackie Robinson, who broke the racial barrier in Major League Baseball, and Ralph Bunche, the first Black American to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Still, Johnson encountered racism on campus. One white woman he was seeing was forced to choose between her sorority membership and dating a Black man. A fraternity rejected Johnson as a member because he was Black. But he was accepted elsewhere and became the first Black American to join a national fraternity at UCLA — Pi Lambda Phi.

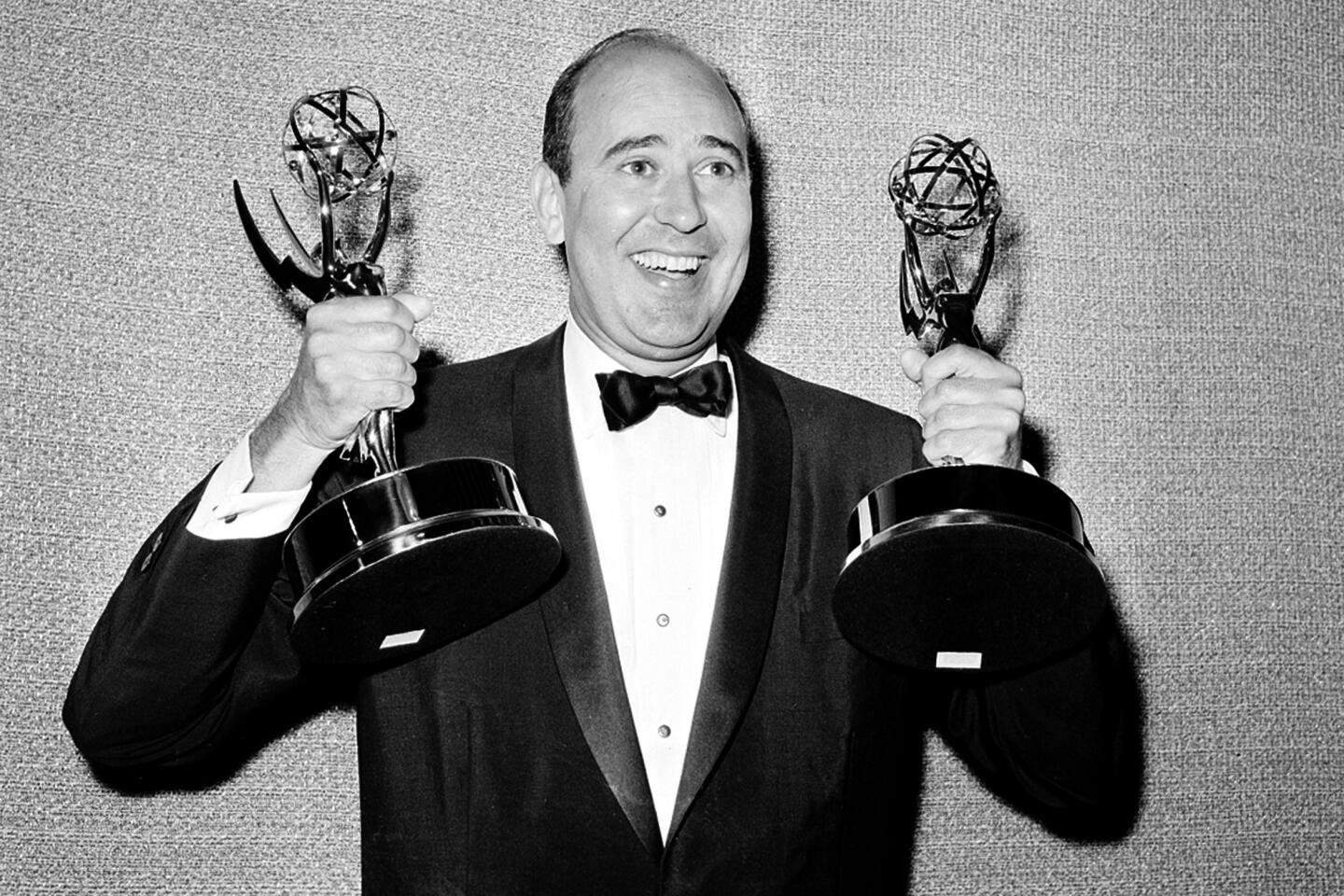

Johnson’s fast ascendancy as a decathlete drew national attention. He won the Pan American Games in 1955, earning a spot on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” He then broke the world record for the decathlon, establishing himself as the favorite for the 1956 Olympics.

But a knee injury and torn stomach muscle hampered Johnson and he finished second at the Games in Melbourne, Australia, a bitter disappointment.

Back at UCLA, Johnson was elected student body president, a position that brought him “a pile of hate mail,” he recalled, with one letter asking, “Who do you think you are, black boy?”

In 1958, with Cold War tensions at their height, much of the world’s attention was drawn to the first U.S.-USSR track meet, to be held in Moscow. In the spotlight was the battle to be the World’s Greatest Athlete between Johnson and Vasili Kuznetsov, who held the world record then.

Onlookers built it up as a battle between communism and the free world, a role that made Johnson uncomfortable.

“I was fully aware of the irony that a Black man was an emissary of a nation where discrimination raged and racists got away with lynchings,” he said. “I found myself affected by the political overtones despite my efforts to ignore them.”

In the end, Johnson turned in his best decathlon yet, beating Kuznetsov and again breaking the world record. When it was all done, the Soviet crowd rushed the field, and Johnson thought they were going to attack him. Instead, they raised him on their shoulders and shouted his name.

“Never in the history of track has an athlete performed so well as Rafer Johnson in Moscow,” wrote Sports Illustrated.

In 1958-59, Johnson played basketball for legendary UCLA coach John Wooden and began training with Yang, a Taiwanese athlete who had come to UCLA and emerged as a decathlete nearly as strong as Johnson. The competitive rivals would develop a unique friendship.

“Ours was the purest of rivalries,” Johnson recalled. “We each wanted the other guy to do well, but we wanted even more to win.”

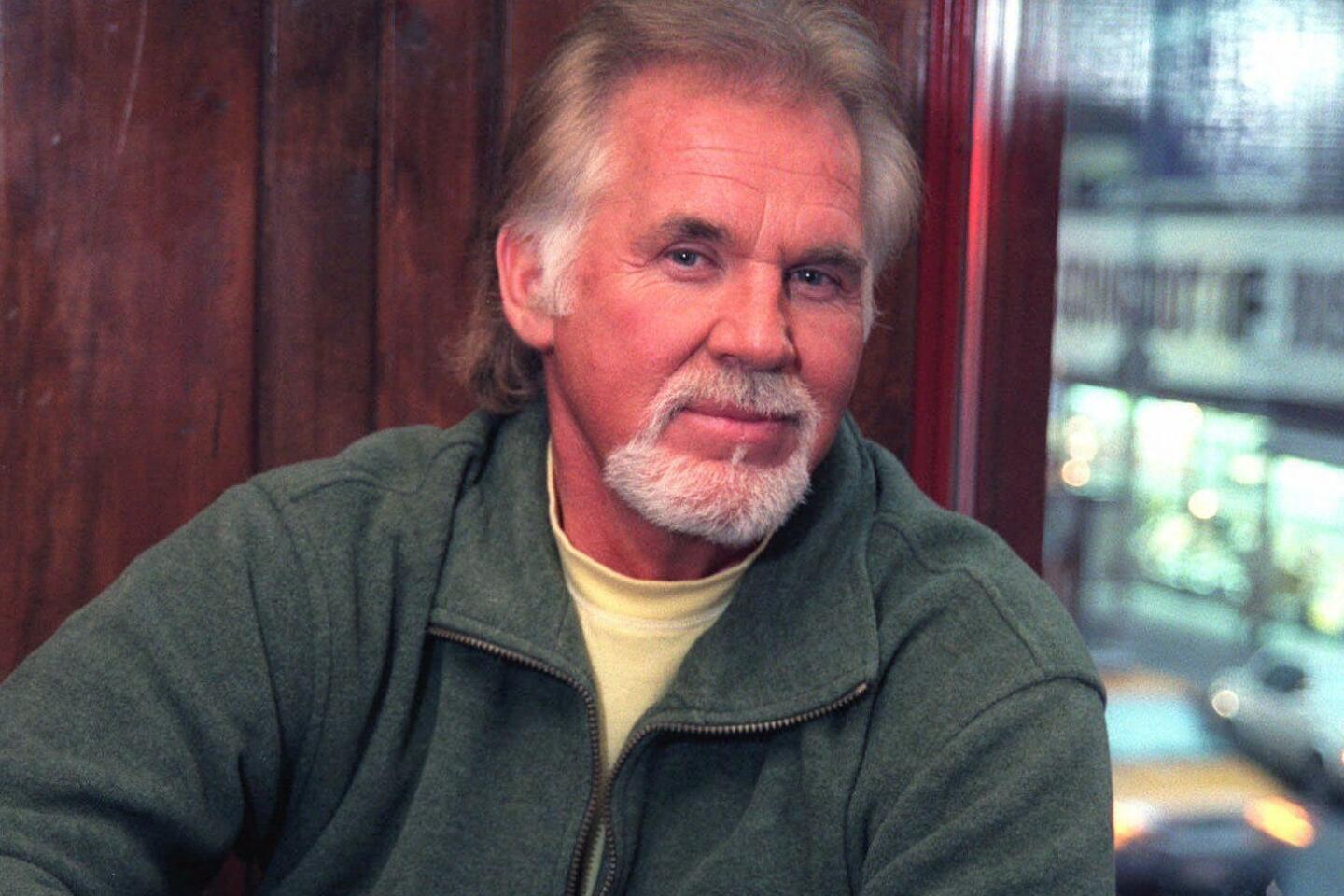

A life in photos

Though Olympic success could cement an athlete’s fame, the rules of amateurism at the time kept Johnson from cashing in. He had to turn down a role in the movie “Spartacus” for fear it would endanger his eligibility and, for a while, he was forced to pay his bills flipping burgers at Culver City’s Hamburger Handout.

Johnson hurt his back in a 1959 car accident, forcing him to sit out a year’s worth of competition, and raising questions about whether he could compete at the 1960 Olympics in Rome.

But that doubt was erased when Johnson won the 1960 Olympic trials, yet again setting a new world record in the process.

Johnson’s two-day battle with Yang in Rome was a drama-fueled duel. The first day’s events were interrupted by downpours, keeping the athletes on the track until nearly midnight. Johnson, leading Yang by a small margin of 55 points, got just five hours’ sleep. No other competitors were close to the two leaders.

By 10 p.m. on the second day, Johnson led Yang by just 67 points with only the final event — the 1,500-meter run — remaining. Johnson hated the 1,500 and Yang was better at it. If Yang beat Johnson by more than 10 seconds, the gold would go to him.

But Johnson determinedly stuck on Yang’s heels lap after lap and ran the fastest 1,500 meters of his life. He finished just 1.2 seconds behind Yang, claiming the gold medal. An exhausted Johnson immediately announced he was retiring from the sport.

Johnson’s victory brought him attention from surprising places. In 1961, the Los Angeles Rams picked him in the NFL draft, though Johnson hadn’t played football since high school. He also was offered a spot on the Harlem Globetrotters.

He passed on the offers and instead dabbled in the movies, landing supporting roles in about a dozen films and several TV shows.

Johnson had a short career as a TV reporter, covering the 1964 Olympics for NBC and then working as a sports anchor for KNBC in Los Angeles.

At an awards dinner in 1961, Johnson met Kennedy, then the U.S. attorney general. Their political and social views meshed and they quickly became friends. Soon, Johnson was a regular guest at Kennedy’s homes in Virginia and Massachusetts on Cape Cod, playing touch football and scuba diving off Edward M. Kennedy’s yacht.

When Robert Kennedy announced his run for president in 1968, Johnson jumped in with full support, addressing rallies, speaking at news conferences and meeting with voters. At public events, Johnson and former Rams football player Roosevelt Grier stayed so close to Kennedy that people thought they were his bodyguards.

On the night of June 5, 1968, Kennedy spoke to jubilant supporters at the Ambassador Hotel in L.A. after winning the California Democratic primary. As he went to leave, gunshots rang out, and Kennedy fell, mortally wounded.

Johnson and others rushed the gunman, Sirhan Sirhan, and Johnson said he grabbed the gun, still in Sirhan’s hand. Johnson said he twisted Sirhan’s fingers to get the gun loose, and put it in his pocket. Hours later on the chaotic night, Johnson realized he still had the gun and turned it over to police.

Kennedy’s assassination left Johnson traumatized and depressed, but he found a new direction by helping launch the California Special Olympics, the athletics event for disabled children. It was a cause he remained involved in the rest of his life. From 1983-92, he was president of the Special Olympics Southern California. He also had a long career at Continental Telephone, rising to vice president of personnel.

In 1971, Johnson married Betsy Thorsen and they had a daughter, Jennifer, and a son, Joshua, all of whom survive him.

In 1979, L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley asked Johnson to join the board of the committee bringing the 1984 Summer Olympics to the city.

As the Games approached, speculation swirled about who would be the final torchbearer, usually an athlete who stirred exceptional pride in the host nation. Would it be Mark Spitz, winner of seven gold medals in swimming in 1972? Bruce Jenner, the 1976 Olympic decathlon champion?

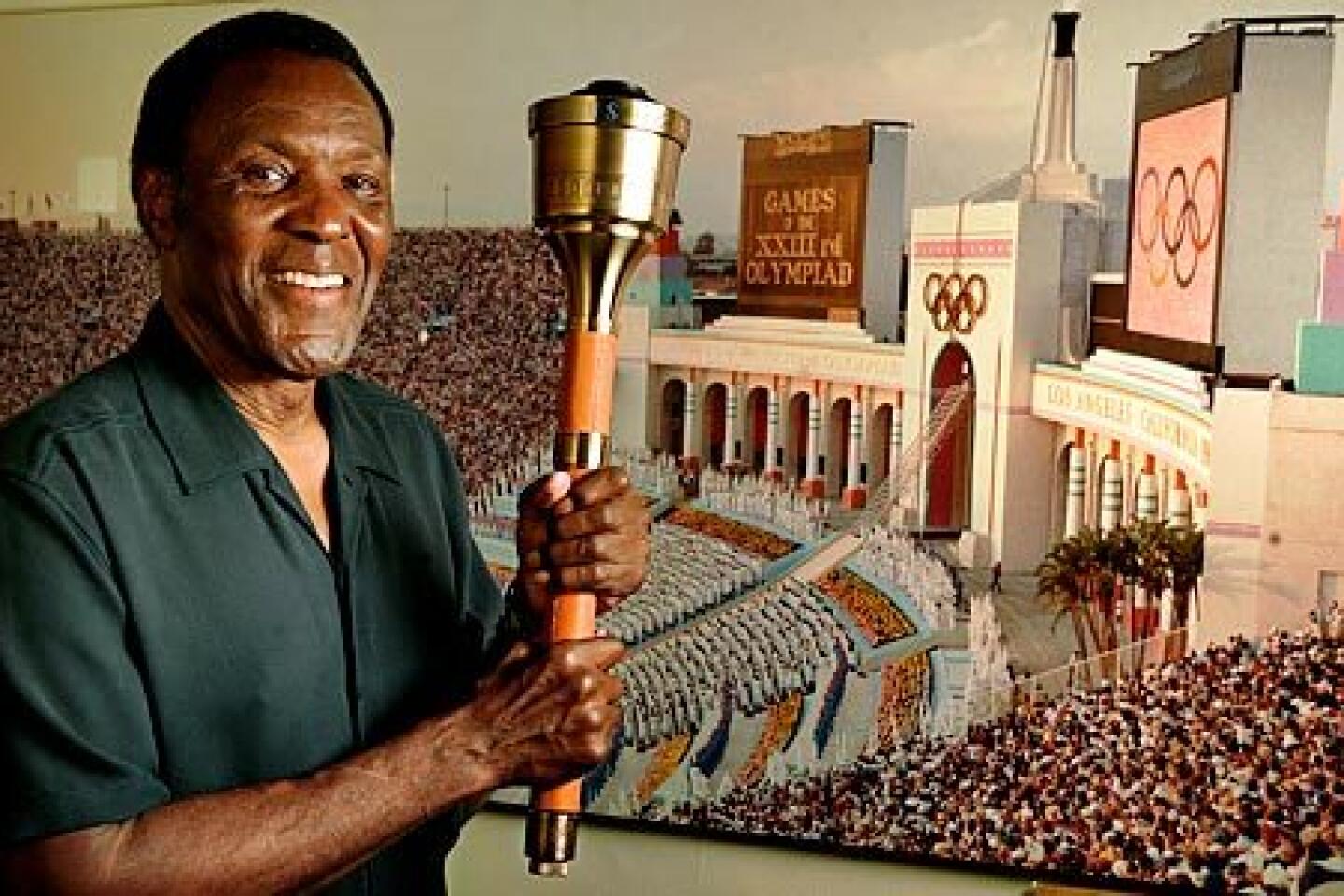

About 10 days before the July 28 ceremony, Johnson was called to a meeting with Peter Ueberroth, president of the organizing committee, and David Wolper, the producer of the opening ceremony. Ueberroth said he wanted Johnson to light the flame.

“By the time his words left his breath and hit my ears, I had said yes,” Johnson recalled.

Five years earlier, Johnson had cast the deciding vote in the balloting that elected Ueberroth president of the organizing committee. But Ueberroth was always adamant later that Johnson was not chosen to light the flame as a gesture of gratitude.

Johnson was ordered to keep the news quiet. The media were chasing it and Ueberroth, who loved the intrigue, wanted it to be a surprise, as the announcement of the final torchbearer usually is.

So Johnson told only his wife, and began his workouts during a family vacation at her parents’ home in Newport Beach. “I got a couple of five-pound weights,” he said, “and I ran up and down inside a parking garage.”

Johnson was 49 at the time, but in rehearsals for the opening ceremony, Wolper was making his torchbearer feel like an old man.

“Those steps were killers,” Johnson says. “I never got all the way up in rehearsals.”

On the temporary ladder at the top, each step was white, each was narrow. The ladder tended to rock if Johnson didn’t stay in the center. So he had them paint black dots in the center of each step, and two dots in the center of the top step.

At Johnson’s request, workers drilled a 36-inch fiberglass pole on the top step that stood to his left as he faced the crowd and gave him a handhold.

At the ceremony, Johnson received the torch and started up the stairs. On the temporary ladder he concentrated on the dots.

“When I got up there, and I turned and saw the crowd, saw that view, and there was nothing behind me, and I’m standing on something about a foot wide, I know I would have fallen. I can’t even explain the feeling. My heart was pounding in my chest. I felt like I was going to die.”

He raised the torch to the gas jet attached to the bottom of the arch. He heard a whoosh. The flame took and rose, through the rings, up to the cauldron, which erupted in fire.

Watching on television, Johnson’s former broadcasting colleague Tom Brokaw spilled tears of pride.

“I thought about the whole arc of his life. And how I’d always believed, well before I knew him personally, that he was the quintessential American athlete.”

Staff writer David Wharton contributed to this article.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.