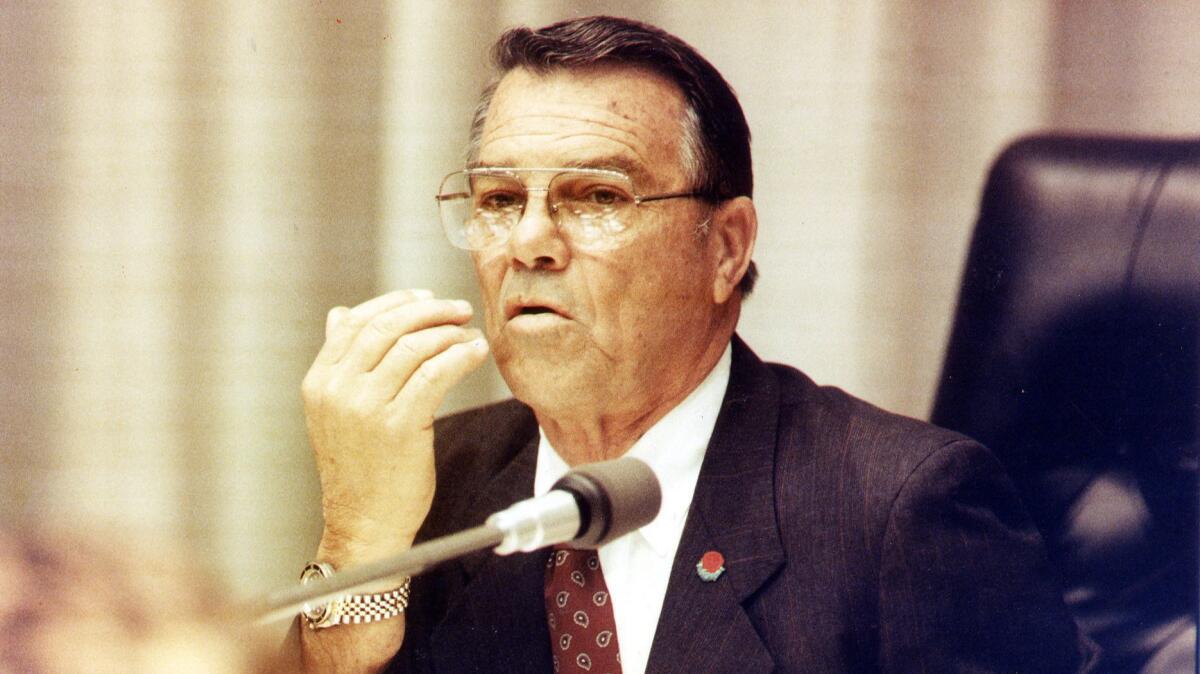

Pete Schabarum, L.A. County supervisor and father of California’s term limits, dies at 92

Pete Schabarum, the famously combative, influential Los Angeles County supervisor whose successful state term-limits ballot drive more than two decades ago dramatically altered California government, has died at age 92.

For the record:

11:32 a.m. Aug. 6, 2021This obituary states that Schabarum died Aug. 1. He died Aug. 2.

A mainstay in the L.A. political scene for decades, Schabarum died Sunday of natural causes, his family said.

A commercial real estate developer and lifelong Republican who began his political career in the state Assembly, Schabarum spent 18 years on the powerful, five-member county Board of Supervisors.

For nearly a decade, after helping engineer the 1980 election of two more Republicans, he anchored a three-member conservative majority that reshaped county government. The new majority shifted money away from healthcare and other services for the poor to law enforcement and other safety programs, encouraged development of vast tracts of open land, phased out rent controls and angered public employee unions by farming out county work to private contractors after Schabarum spearheaded a successful ballot measure allowing wider use of the practice.

Changing demographics and a lawsuit over new board districts pushed Schabarum, by then estranged from his fellow supervisors, into a reluctant retirement in 1991.

But his widest impact almost certainly came with the controversial Proposition 140, the ballot measure he rallied California voters around in 1990. It shortened the careers of scores of state politicians and set up a regular turnover of seats among less experienced lawmakers that continues today.

As voters in other states began enacting similar measures, their counterparts in some local governments, including the city of Los Angeles, followed suit and Schabarum became known, to critics and admirers alike, as the “father of term limits.”

In a 2012 interview, Schabarum said he was disappointed with the way things turned out. He had intended that office holders serve briefly before returning to their previous fields and he hadn’t anticipated career politicians constantly jumping to other offices.

“They spend most of their time looking for the next job” instead of solving the state’s problems, Schabarum said.

Critics said his real motivation was to get rid of longtime Assembly Speaker Willie Brown, the powerful San Francisco Democrat, and to lash out at fellow pols as his own career was winding to a frustrating end.

Once asked if he would introduce a term-limits proposal for fellow county supervisors to consider, Schabarum said, “No. Those guys think they are the lifeblood of government.” (It took until 2002 for L.A. County voters to enact term limits.)

Schabarum always denied any personal vendetta behind the term-limits measure, saying he wanted only to scale back what he saw as an outsized state government and turn it over to citizen legislators. As election night returns showed voters had chosen Prop. 140 over a less strict term limits proposal, he said the measure “changes the face of politics.” Aides saw a potential new career for their boss as the catalyst for a national movement.

That didn’t happen. Schabarum’s last turn on the public stage was far different from what supporters had imagined. In 1997 he was indicted by a county grand jury on theft and tax evasion charges in connection with funds from a nonprofit “good government” foundation he was illegally using to pay for vacations.

Saying he was too old and too concerned about “political” fallout to endure a criminal trial, Schabarum, then 68, pleaded guilty to three counts of felony tax evasion. He agreed to serve three years’ probation, perform 250 hours of community service and pay more than $65,000 in fines, back taxes and restitution. A judge later reduced the felonies to misdemeanors.

Schabarum, by then legally blind from a degenerative eye disease, spent his retirement years in Indian Wells, traveling with friends, attending 49er reunion weekends in San Francisco and keeping up with politics. He said the state’s open primary system, approved by voters in 2010, was “worth a try” if it could “get rid of radicals on the left and the right and bring more moderate [candidates] to the fore.”

“I made a mistake,” a contrite Schabarum told the judge who reduced his convictions in 1998, adding that he had never intentionally violated the law.

The case was believed to have been the first major test of state laws created to prevent politicians from cashing in on unused campaign war chests once they leave office. Schabarum had converted his leftover funds to the Foundation for Citizen Representation, which he agreed to dissolve as part of his plea bargain.

Schabarum’s lawyer at the time of the plea bargain, John Barnett, said the former supervisor had been singled out for prosecution because of his politically unpopular stance on term limits. Prosecutors and good-government groups scoffed at that notion.

The case was a humiliating coda to a long and successful — if controversial — career for the blunt-spoken supervisor whose competitive spirit once led him to mow down a petite grandmother during a county softball game.

Peter Frank Schabarum was born Jan. 9, 1929, in Los Angeles and grew up in the San Gabriel Valley.

In 1951, he earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from UC Berkeley, where he was an all-conference halfback for the Golden Bears and played in three Rose Bowls. Upon graduation, he joined the San Francisco 49ers and played through the 1953-54 season, with time off to serve in the Air Force during the Korean War.

After leaving pro football, Schabarum returned to Covina and started Schabarum Companies, building into it one of the area’s leading development firms. He married the former Gerry Ann Curtice and they raised two sons and a daughter.

Gerry Schabarum died in 2007; the couple had been married 48 years. He is survived by his three children, Laura Vandivort, Frank and Tom; and four grandchildren, Kimberly Hansen, Kevin, Elena and Curtice.

Schabarum got his start in public service in 1965 with a stint on the Los Angeles County Grand Jury, becoming at 36 its youngest-ever foreman. Election to the state Assembly came the following year, representing the San Gabriel Valley, and he was reelected twice before the March 1972 death of longtime county Supervisor Frank G. Bonelli set Schabarum on a different course. Then-Gov. Ronald Reagan appointed Schabarum to fill the unexpired term. He won election to the post that June and was reelected four times.

He said he was happy to be back home, where he could indulge his passions for horseback riding and hunting and often played tennis with one of his political opposites, Supervisor Ed Edelman, a liberal Democrat. Peter F. Schabarum Regional Park in Rowland Heights is named in his honor.

But Schabarum was often frustrated at being on the short end of the board’s 3-2 ideological split, so in 1980 he dipped into his campaign funds to help elect the like-minded Mike Antonovich and Deane Dana and, with Schabarum as board chairman, the three set the county on a new conservative course. His relations with his new colleagues, whom he pointedly criticized when he disagreed with them, eventually soured.

Schabarum lost out in a protracted remapping battle that wound up in court and placed him in a new district that was heavily Latino. When he retired, he was succeeded by Gloria Molina, whose election marked the return of a 3-2 liberal tilt.

He said he didn’t mind being unpopular.

“You get things done around here by using the tools available, one of which is to be a crusty curmudgeon,” Schabarum told The Times on the eve of his 1991 retirement. ”I, more so than any other person on this board, have done one heck of a lot more getting things done.”

Merl is a former Times staff writer

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.