What would a Republican president do about Ukraine?

Here’s what the United States has done so far in an attempt to deter further Russian incursions into Ukraine: applied two rounds of economic sanctions and asked Congress to approve $1 billion in loan guarantees for Kiev.

Here’s what President Obama says he won’t do:

“We are not going to be getting into a military excursion in Ukraine,” he told a television station in San Diego last week.

PHOTOS: A peek inside 5 doomed dictators’ opulent lifestyles

The president’s careful response and unwillingness to consider military intervention has met with general support from other Democrats. But Republicans have been sharply critical.

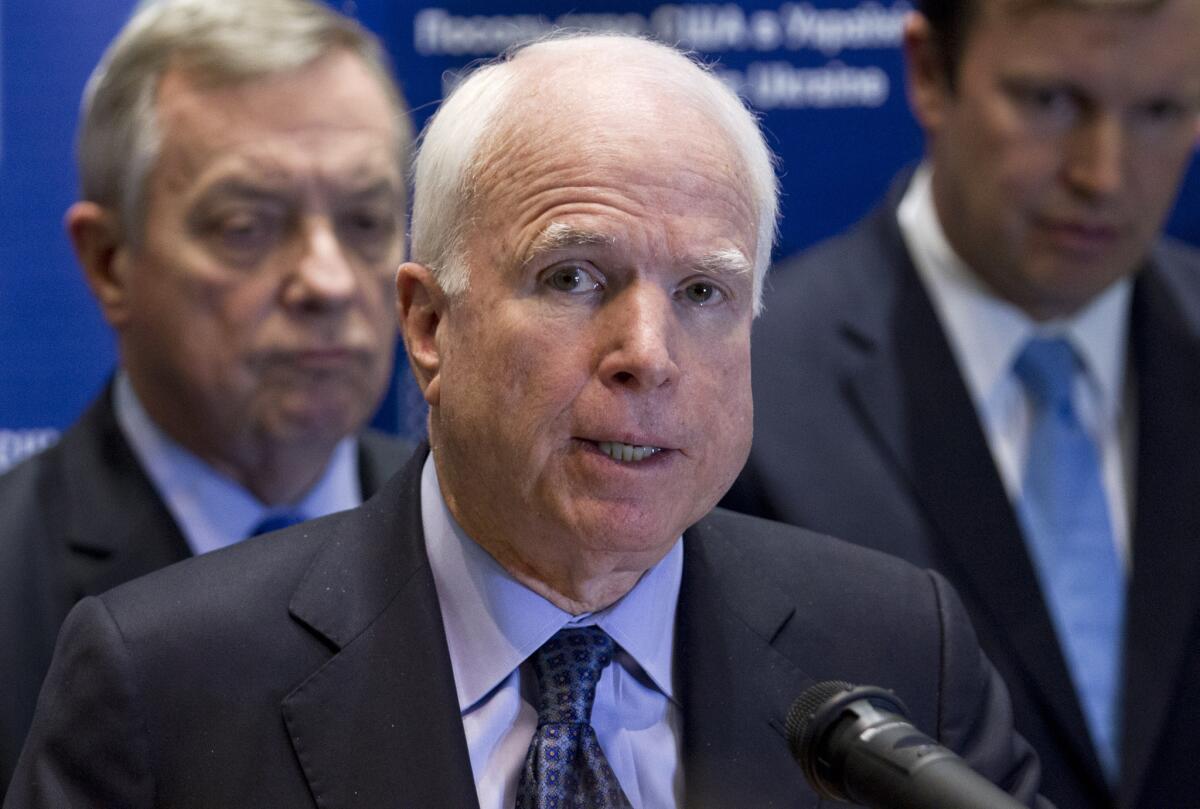

“This is the ultimate result of a feckless foreign policy in which nobody believes in America’s strength anymore,” Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) charged this month.

The sniping is no surprise given the partisan divide in Washington. But would a Republican in the White House instead of Obama actually plot a different course?

That would depend entirely on which Republican we’re talking about. The GOP has long been divided on foreign policy, and Ukraine has exposed fault lines that are likely to grow as the Republicans’ 2016 nomination contest nears.

On foreign policy in general, and on Ukraine in particular, Republicans fall into three camps: hawks, realists and libertarians.

Let’s start with the hawks. McCain, the hawk’s leading voice on Ukraine, has been warning against a resurgent Russia at least since his 2000 presidential campaign, when he called for sanctions against Putin over Russia’s actions in Chechnya. In the current crisis, he is still not calling for U.S. boots on the ground, but he has called for immediate shipments of small arms and ammunition to Kiev, as well as U.S. intelligence-sharing. “The United States should not be imposing an arms embargo on a victim of aggression,” he said last week.

Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), a younger hawk, has gone a step further, calling not only for military aid to Kiev but also for suspending cooperation with Russia on other diplomatic projects, including negotiations with Iran. “Put simply, Russia should no longer be considered a responsible partner on any major international issue,” Rubio wrote last week in what amounted to a call for a new Cold War.

William Kristol, editor of the Weekly Standard, may be the most hawkish of the hawks. Last week, he told CNN that “deploying ground troops … should not be ruled out.”

Closer to the center of the GOP is moderate conservative Sen. Bob Corker (R-Tenn.), the top Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a realist when it comes to foreign policy.

Corker had the courage to praise Obama’s economic sanctions as “a step in the right direction,” although he said he thought the president should add tougher measures. “We should send some shock waves through the Russian economy,” he told me.

But military aid can wait, Corker said. “I don’t know that that’s something we should be doing right away.”

Over the long run, the United States should strengthen its military relationship with Ukraine, Corker said -- but not now, in the heat of the crisis. “Military assistance isn’t the priority today,” he said. “It’s to establish with the Ukrainians that we’re going to be with them over the long haul.”

The calmest part of the Republican Party when it comes to Ukraine may be its most traditional realists, who ran foreign policy during several presidencies.

The main U.S. goal in Ukraine, former national security advisor Brent Scowcroft said last week, should be to make sure the conflict in Russia’s backyard doesn’t spread to other countries or other issues.

“I don’t think it’s an issue of that great consequence,” Scowcroft said of Crimea. It would be a mistake, he said, to try to match Russia “belligerence by belligerence.”

“That may be where we end up, but I doubt we have to start there.”

Finally, there are the libertarians, which brings us to Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), who’s at the top of early polls of potential Republican presidential nominees. Paul has been working hard in recent months to make his positions sound closer to the party’s mainstream, which means criticizing the president and trying to sound hawkish.

But as a libertarian, he still wants to wage a minimalist foreign policy. The current situation has left him sounding a bit incoherent.

“If I were president, I wouldn’t let Vladimir Putin get away with it,” Paul announced in a column in Time magazine. What would he do? Among other steps, he’d suspend all U.S. economic aid to Ukraine, because some of the money might end up in Russia. In short, he’d destroy the Ukrainian economy in order to save it.

But the senator didn’t go as far as his far more isolationist libertarian father, who wrote in USA Today that even that much activism in Ukraine would be too much. “Why does the U.S. care which flag will be hoisted on a small piece of land thousands of miles away?” Ron Paul wrote. “So what?”

And that attitude may have the most resonance with the American people. A Pew Research Center poll conducted in early March, before Crimea was annexed, found that most Americans believed the United States should “not get too involved” in the conflict. That included 50% of Republicans, against only 37% who favored taking a firm stance against Russia.

The crisis in Ukraine has presented a new opportunity for Republicans to snipe at the Obama administration, and they have embraced the task enthusiastically. But the pile-on isn’t without risk. Debate about what to do about Russia has also caused new fissures within the party, and they’re unlikely to be healed before 2016.

Twitter: @DoyleMcManus

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.