Opinion: From the grave, Scalia calls B.S. on Trump’s video-game theory

- Share via

President Trump has had a lot to say about school shootings in the last couple of days, some of it alarming, such as his notion that schoolteachers who are “gun adept” could be armed.

But I was most struck by Trump’s suggestion at a White House meeting on school safety that “violent” video games might be the culprit in school shootings. (Nikolas Cruz, the accused school shooter in Florida, reportedly played video games for as long as 15 hours a day.)

“We have to do something about maybe what they’re seeing and how they’re seeing it,” Trump mused. “And also video games — I’m hearing more and more people say the level of violence in video games is really shaping young people’s thoughts.”

Scalia was especially devoted to the free-speech protections of the 1st Amendment, and one of his most memorable 1st Amendment opinions involved video games.

Who are these people attributing violence to video-game watching?

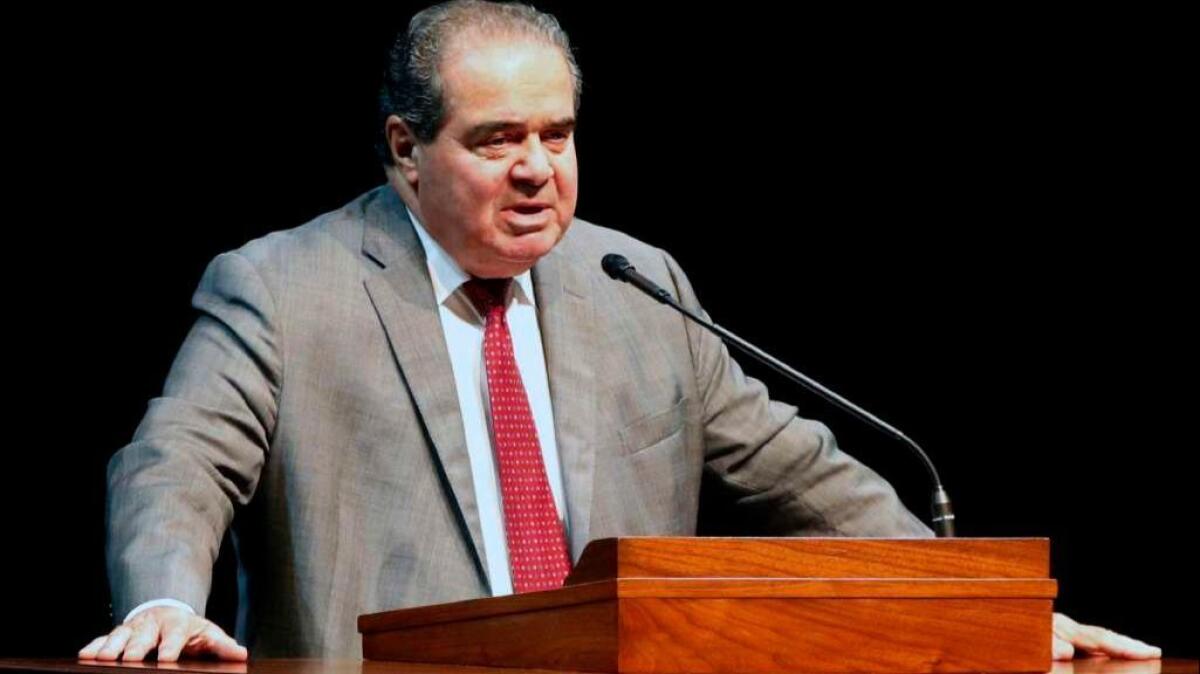

We know who one of them isn’t — or rather wasn’t: Antonin Scalia, the man Trump called “a brilliant Supreme Court justice, one of the best of all time,” after Scalia’s sudden death in 2016. Then-candidate Trump added that Scalia’s career “was defined by his reverence for the Constitution and his legacy of protecting Americans’ most cherished freedoms.”

Scalia was especially devoted to the free-speech protections of the 1st Amendment, and one of his most memorable 1st Amendment opinions involved ... video games.

In 2011, Scalia wrote the majority opinion in a decision in which the court struck down a California law — signed by that foe of violent entertainment Arnold Schwarzenegger — that restricted the sale of “violent” video games to minors. (The Los Angeles Times saluted that decision in this editorial.)

In his opinion, Scalia mocked the research that purported to show a connection between watching video games and aggressive behavior. All it actually demonstrated, he said, was “at best some correlation between exposure to violent entertainment and minuscule real-world effects, such as children’s feeling more aggressive or making louder noises in the few minutes after playing a violent game than after playing a nonviolent game.”

This footnote is my favorite part of the opinion:

“One study, for example, found that children who had just finished playing violent video games were more likely to fill in the blank letter in ‘explo_e’ with a ‘d’ (so that it reads ‘explode’) than with an ‘r’ (‘explore’). The prevention of this phenomenon, which might have been anticipated with common sense, is not a compelling state interest.”

(Scalia had nine children, so he may have been relying on experience here.)

Trump is often mocked for poor sourcing of his arguments. It’s hard to trust a president who introduces a debatable proposition with “I’m hearing more and more people say.” But sometimes dubious claims come from credentialed experts in the social sciences. Scalia wasn’t afraid to call B.S. on those who would use their findings to justify limits on free speech.

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.