Opinion: Clarence Thomas, echoing Trump, all but called American libel law fake news

- Share via

Few of Donald Trump’s pronouncements inspired such fear and loathing among journalists as his famous campaign pledge to “open up our libel laws” to make it easier for aggrieved public figures such as himself to win defamation suits against the press.

Of course, as I pointed out here, there really aren’t any federal libel laws for Trump to open up. Federal courts do hear libel cases, but they are tried under state law. “The only influence a president can have on libel law,” I wrote, “is through his appointment of federal judges, especially Supreme Court justices, whose interpretations of the 1st Amendment can affect the prospects of libel plaintiffs.”

This just in: On Tuesday morning a Supreme Court justice suggested that the court reconsider the mother of all “liberal” libel decisions, New York Times vs. Sullivan (1964), which makes it extraordinarily hard for public officials to win a libel lawsuit. (Later decisions extended the rule to cover nongovernmental “public figures.”)

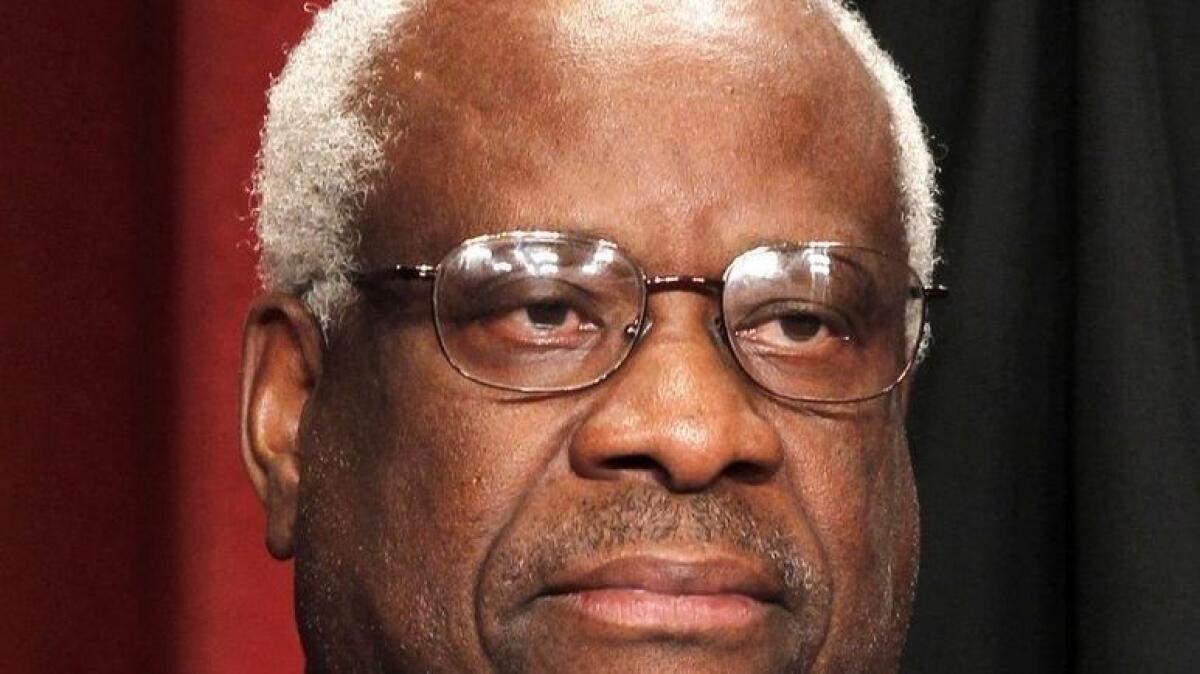

But here’s the twist: The justice wasn’t one of Trump’s two appointees. It was Justice Clarence Thomas, a George H.W. Bush nominee, and he’s probably alone on the court in wanting to revisit the Sullivan case. (As Adam Liptak notes here, Trump’s nominees, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, seem to be in the mainstream on libel law.)

Thomas’ call for reconsidering Sullivan and subsequent rulings “in an appropriate case” came in an opinion — signed only by him — in connection with the court’s decision not to hear an appeal by Kathrine McKee, who tried to sue Bill Cosby for defamation. McKee, who had claimed the comedian raped her, argued that a letter about her she said was leaked by Cosby’s lawyer distorted her background to “damage her reputation for truthfulness and honesty, and further to embarrass, harass, humiliate, intimidate and shame her.”

But what tripped McKee up was the fact that the court below, relying on the Sullivan case and subsequent decisions, said she was a “limited-purpose public figure” because she had thrust herself to the forefront of the public controversy over sex assault allegations against Cosby. Under Supreme Court precedent, she therefore would have to prove that a defamatory statement about her was made with “actual malice” — that is, “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” The lower court concluded she couldn’t meet that burden.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

The “actual malice” rule — which doesn’t have anything to do with the common-sense definition of actual malice (“I hate you”), has been a life preserver for many a news organization sued for libel, though the beneficiary here happened to be a show-business celebrity.

Thomas essentially accused previous Supreme Courts of making it all up.

He wrote that neither the Sullivan decisions nor later rulings expanding its protections were grounded in the Constitution’s “original meaning.” The author of the Sullivan decision, Justice William Brennan, had relied on a broader constitutional principle: “a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”

This isn’t the first time that Thomas has espoused a minority view. For example, he has questioned whether the 1st Amendment’s ban on the “establishment” of religion by government — think official prayers in public schools — applies to the states.

Arguably it’s healthy for the court to include one maverick justice who tenaciously tilts at windmills. If nothing else, Thomas’ quirky jurisprudence makes law school constitutional law classes interesting.

So why has Thomas’ revisionism on this issue created a sensation? It’s surely because his critique seems to echo Trump’s. It’s almost as if he accused the Sullivan decision of being “fake law.” But, as with the president’s broadsides against the press, it’s important not to panic. One opinion by a justice renowned for his eccentricity doesn’t mean that New York Times vs. Sullivan will be trumped.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.