Op-Ed: The year in outrage: Our constant indignation is wearying, but often necessary

A photo for use with the Dec. 21, 2015 Berlatsky “Year in outrage” op-ed.

- Share via

Outrage over outrage over outrage is the new outrage over outrage. Journalistic umbrage has been churning since long before the sinking of the Maine sent Joseph Pulitzer into war-mongering hysterics. But social media has accelerated the cycle of denunciation and backlash and backlash to the backlash, as pundits line up to condemn the endless click-bait condemnation, and bemoan the culture of moaning. The relentless grind tends to flatten out the distinction between the trivial and the significant. Celebrity gaffes and actual evils roll past together on the news feed, each pleading for attention and emotional investment with the same voice.

Perhaps the most disturbing consequence of constant outrage is that, over time, one incident bleeds into the next. Unvaried incredulity turns into white noise, a meaningless hum. We remember that we were angry — very, very angry — but not why.

As a refresher, here’s a brief look back at the year in outrage.

The cover of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo featuring the Prophet Mohammed is seen displayed with front pages for newspapers from around the world outside the Newseum in Washington on on January 14.

In January, Islamic extremists attacked the offices of French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo, killing 11 people. The horrifying murders touched off a lengthy back-and-forth about Charlie Hebdo’s legacy, with some expressing outrage that the magazine used racist imagery and others outraged that anyone would say the imagery was racist.

In February, Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” failed to win the Academy Award for best picture on a night when all of the 20 major actor nominations went to white performers. The monochromatic selections led blogger and lawyer April Reign to coin the hashtag #Oscarssowhite, prompting tens of thousands of tweets. “They didn’t see Selma but their housekeeper said it was really good,” writer Jamie Nesbitt Golden tweeted. Outrage: It can smile as it sticks the knife in.

Trevor Noah appears on set during a taping of “The Daily Show with Trevor Noah” in September in New York.

In March, Trevor Noah was named as the next “Daily Show” host. Seconds later, the Internet turned up old tweets in which he made dumb jokes about less-than-perfectly-slender women and Jews. There was outrage, and outrage at the outrage, which has now largely faded into mild irritation that Noah’s “Daily Show” is not very funny.

Demonstrators climb on a destroyed Baltimore Police car during violent protests following the funeral of Freddie Gray on April 27, in Baltimore, Maryland.

In April, Freddie Gray, an African American, was injured in a Baltimore police van. He later died from spinal cord injuries. Gray’s death led to extended protests, some of which turned violent — prompting condemnation of the Black Lives Matter movement.

In May, the television show “Game of Thrones” featured another gratuitous rape scene. Some fans were outraged and/or just tired of the same damn storyline over and over. Other fans were outraged that anyone would get weary of rape as a plot point.

Rachel Dolezal, center.

In June, it was revealed that Rachel Dolezal, president of the NAACP in Spokane, Washington, was white, despite her longtime claims of being African American. The resulting media hubbub was one part outrage, two parts what on Earth is wrong with her?

Cook County Sheriff, Tom Dart speaks to lawmakers while on the House floor during session at the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield, Ill.

In July, Sheriff Tom Dart of Chicago was outraged that, according to him (based on no real evidence), Backpage.com was promoting human trafficking with ads for adult services. He pushed Visa and MasterCard to stop doing business with the site — a move that U.S. Appeals Judge Richard Posner ruled in December was an outrageous act of “official bullying.”

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, left, and Fox News Channel host and moderator Megyn Kelly during the first Republican presidential debate at the Quicken Loans Arena in Cleveland.

In August, the outrage vortex that calls itself Donald Trump was outraged that reporter Megyn Kelly asked him hard questions during a Fox News debate. Trump said Kelly had been mean to him because she had “blood coming out of her whatever.” People were outraged, but outrage only made Trump stronger.

In September, Monica Foy, a student at Sam Houston State University, wrote an insensitive tweet to her 20 followers about the shooting of a police officer. Right-wing tabloid Breitbart.com was outraged, and wrote a post denouncing her — leading to a firestorm of harassment, including rape and death threats.

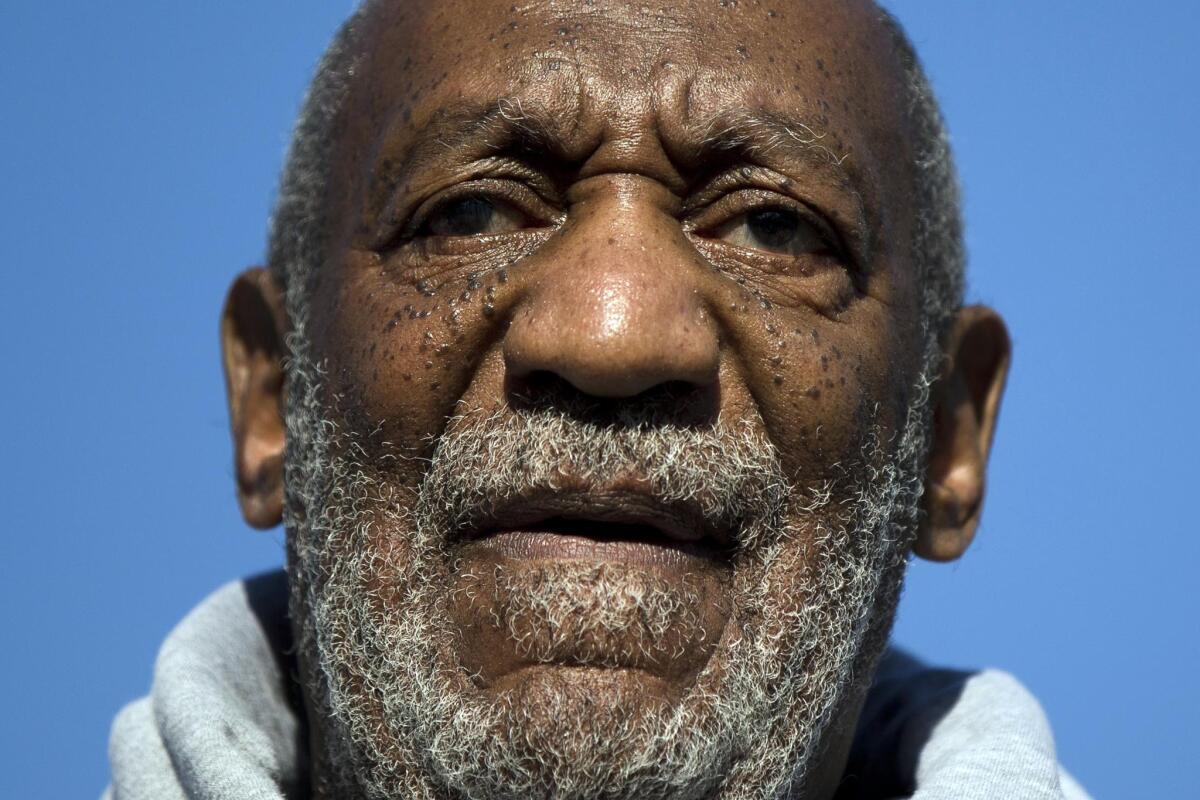

Bill Cosby on Nov. 11, 2014.

In October, Bill Cosby gave a seven-hour deposition about his alleged rape of a minor, reminding everyone that they were still disgusted by a guy who used to be seen as America’s favorite dad. Now that more than 50 women have accused him of sexual assault, Cosby is set to be a source of general nausea well beyond the end of the year.

In November, a fight over Halloween at Yale extended beyond campus. The controversy erupted because administrators sent a memo advising students not to wear racially insensitive costumes; then a lecturer questioned the need for the memo; next, students denounced the lecturer. Finally, national media denounced the students and the totalitarian dystopia their outrage foreshadowed.

In December, Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, opened fire at a party in San Bernardino, killing 14. The incident sparked outrage about gun violence, backlash outrage over gun control, outrage over Muslim violence and backlash outrage over Islamophobia.

*******

Looking back, some of this outrage seems overblown or actively harmful — inciting death threats against a college student for an errant tweet is an exercise in cruelty and bullying, not a blow for righteousness.

In other cases, outrage was necessary. Cosby was humming along cheerfully for years before Hannibal Burress’ comedy sketch ignited enough outrage to damage Cosby’s career. Similarly, until the Black Lives Matter movement, incidents of police brutality were largely dismissed in the mainstream as accidents devoid of broader meaning.

Without outrage, it’s hard to see systemic problems, much less work toward solutions. Outrage is wearying in part because it’s relentlessly commodified; moral panic sells. But outrage is also wearying because there’s so much injustice in the world, and confronting it can seem hopeless.

Still, democracy depends on the belief that normal people, going about their business, are outraged when they see injustice, and want to change it.

Noah Berlatsky edits the comics and culture website the Hooded Utilitarian and is the author of the book “Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.