Op-Ed: A higher minimum wage won’t bankrupt businesses. Low wages might

Eighteen states and nineteen cities increased their minimum wages on Jan. 1, raising salaries for an estimated 4.5 million U.S. workers. California’s minimum jumped fifty cents to $10.50 an hour for smaller employers and $11 an hour for companies with more than 26 employees.

An unspoken convention of policy reporting dictates that you cannot mention this fact without also giving space to the business community’s insistence that low-end wage hikes destroy jobs. The actual analysis of that question is not that mixed, however.

The classic 1994 study from Alan Krueger and Andrew Card, looking at counties along the Pennsylvania and New Jersey borders after the Keystone State didn’t raise its wage and the Garden State did, found no correlation between wage hikes and job loss, and if anything a small job increase on the New Jersey side.

While the Fight for $15 has prompted higher wage floors than anything Krueger and Card contemplated, most subsequent analyses agree with their conclusions. For instance, a UC-Berkeley report on the food service industry in Seattle, home to one of the highest minimum wages in America, showed that increases to $13 an hour in 2016 had no effect on employment.

It’s not hard to understand what workers need.

A University of Washington study of the same region did claim that wage hikes led to fewer hours for low-end workers, and 5,000 fewer jobs than there would have been without the increase. UW’s data, however, excluded businesses with multiple locations — which comprise 40% of the local workforce and include precisely the kind of big-box stores and chain restaurants that have significant numbers of minimum-wage employees.

But if you really want to understand why wage increases are not harmful, but actually critical in the current economy, you have to plug into a different controversy, involving the owners of Subway sandwich shops.

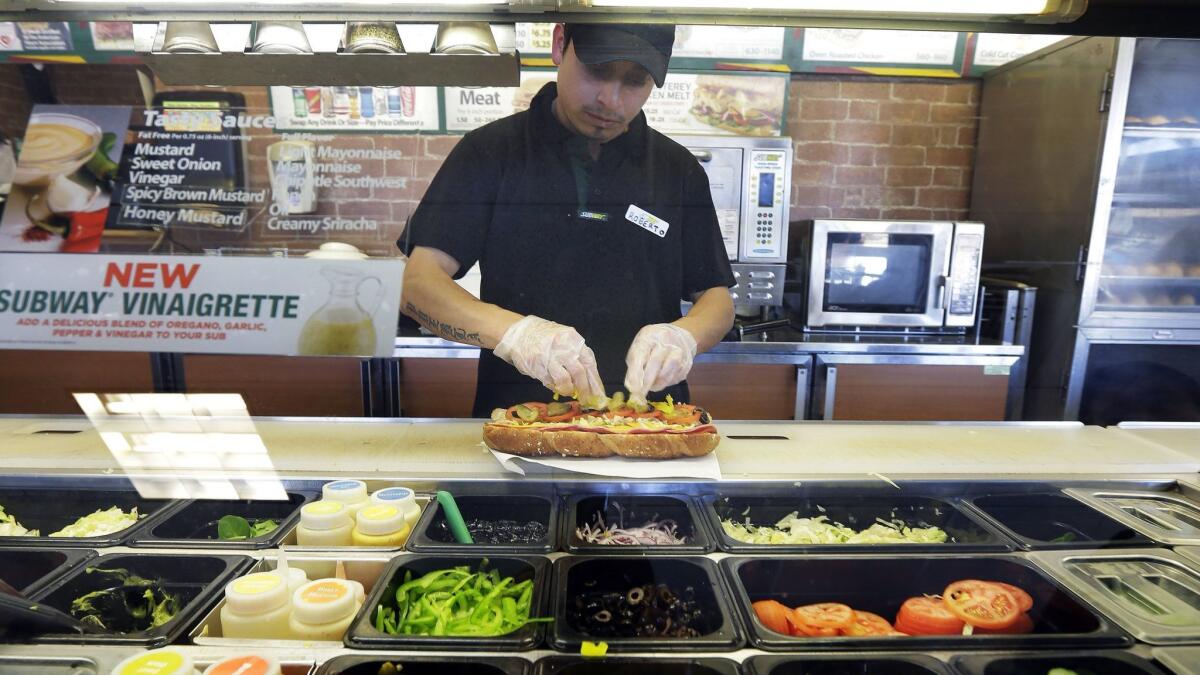

A few weeks ago, about 900 Subway franchisees sent a letter to the parent company protesting the return of the popular “$5 Footlong” promotion. Subway’s corporate executives set menu prices nationwide; franchisees handle day-to-day operations at more than 10,000 locations. Sales have dropped nearly 25% at Subway over the last five years, and management believes the $5 deal is the only way to show investors a reversal of fortune. The franchisees disagree. They wrote that such cheap sandwiches, which barely cover costs, will leave their businesses “unprofitable and even insolvent.”

Beyond Subway, McDonald’s has revived its dollar menu, and Taco Bell, Wendy’s, Little Caesars and Jack in the Box have all prioritized discount items. “The reality in fast food now is that you need a value menu to survive,” market researcher Malcolm Knapp told the Washington Post.

There are several reasons for the price wars, in particular heavy competition from “fast casual” restaurants like Chipotle. But low-end restaurants aren’t the only ones cutting prices to reel in customers. One of the fastest-growing retail chains in America is Dollar General, which pursues the country’s poorest regions for store growth. Target lowered prices on thousands of items in September.

This suggests that purchasing power at the low end of the economy has become so corroded that sellers must fall over themselves to offer prices that barely enable them to make a profit. Whether the franchisees survive is secondary; investors demand companies chase the only growth area for non-luxury goods — the dirt-cheap end of the spectrum.

That’s a result of low wages. Americans did not receive raises from 2007 to 2014, and even that aggregate statistic doesn’t tell the whole story. Wall Street investors encourage companies to cut labor costs; record profits have resulted, with more national income going to the ownership class. Most of the gains since the recession have come at the high end. While low-wage workers are finally seeing some boosts — mostly from minimum wage increases — lack of housing affordability and cost of living rises in areas like health care continue to put them behind.

It’s not hard to understand what workers need. The fact that so many can only afford to shop at severely discounted stores indicates that they don’t make enough money. This fact not only reflects a tragedy for workers, but for businesses, which must sell items practically at cost to generate sales volume.

The clear solution, both for workers and the businesses they frequent, is to raise wages. Henry Ford figured this out more than 100 years ago. Reckoning that consumers and the workforce were one and the same, Ford sought to cycle more money through the economy, increasing the likelihood that people would purchase his cars. He also wanted to lower labor turnover and retraining costs by giving workers an attractive wage.

These aims doubly resonate for minimum-wage jobs. Turnover costs are enormous in fast food and other low-wage sectors. And the correlation between higher salaries and sales is arguably greater in restaurants and retail than for auto assembly lines. Paying people more becomes practically an imperative in an economy so dependent on consumer spending.

Tighter employment markets should take care of this wage conundrum, but only in the areas with the lowest unemployment. Everywhere else, living wages could have a salutary effect, pushing companies out of this race to the bottom on prices and ending the threat of insolvency.

Wage floors won’t bankrupt businesses, but low wages might.

David Dayen is a contributing writer to Opinion.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.