Op-Ed: Is Russia investigator Robert Mueller on a ‘fishing expedition’?

The latest line of attack on the Russia investigation is that it has become, in the words of White House counselor Kellyanne Conway, a “fishing expedition.”

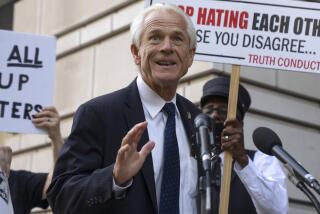

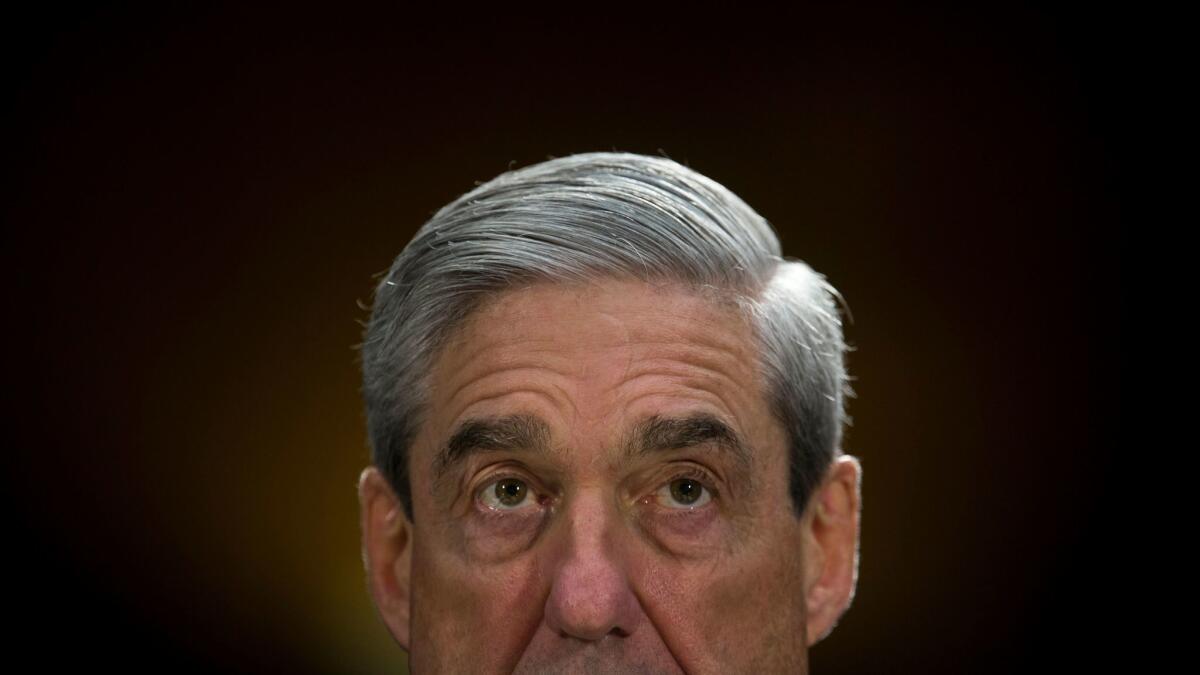

That critique gained momentum with the revelation that special counsel Robert Mueller had obtained a search warrant for tax documents and foreign banking records against former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort. And Trump himself announced a “red line,” declaring off limits any investigation of his pre-campaign financial dealings with Russian entities.

Meanwhile, Deputy Atty. Gen. Rod Rosenstein, who appointed Mueller and set the scope of his authority, took to the airwaves to assure the public that the Mueller investigation is “not a fishing expedition.”

So far, the fishing expedition debate has amounted to little more than name-calling on both sides. There has been no analysis of what the term really signifies, and why it is or is not an effective indictment of Mueller. Rather, “fishing expedition” has been used as a label with the assumption that if it applies, the investigation is not legitimate.

Mueller’s possible inquiry into Trump’s finances is not at all like Starr going after Clinton’s sex life.

Not so. The debate over whether this loosely used term applies is beside the point. The important question is whether Mueller’s conduct is accepted practice, lawful and good for the country.

So framed, the answer is not controversial. Mueller is squarely within bounds.

There is a critical difference between developing evidence of new crimes while pursuing an authorized investigation, and straying outside the borders of legal authority. It’s a familiar principle from other areas of the law. If, for example, the police legally search someone’s house for drugs and find illegal guns, there is no impediment to a gun prosecution.

In short: Where federal authorities are in good faith gathering evidence potentially relevant to the matter under investigation, they may properly use that evidence to develop new charges.

The principle applies with no less force in the case of special investigations into sitting presidents. Consider the example of Webb Hubbell during the Whitewater probe — a 1990s controversy involving Bill and Hillary Clinton’s real estate investments. While in Arkansas questioning witnesses about the Whitewater matter, federal agents uncovered evidence of financial fraud by Hubbell against his (and Hillary Clinton’s) former law firm. Independent counsel Ken Starr pursued the charge aggressively, and Hubbell was sentenced to 21 months in prison.

Hubbell was luckless, but nobody suggested that he shouldn’t have been prosecuted. Even though the fraud had nothing to do with Whitewater, it was clearly fair game to go after him once his wrongdoing surfaced during a legal line of inquiry

Importantly, the Hubbell case preceded and was distinct from the “fishing expedition” charge that was leveled against Starr for expanding his investigation to the president’s affair with Monica Lewinsky. He didn’t stumble across that matter; it was an entirely separate issue brought to Starr’s attention by Lewinsky’s friend Linda Tripp, and it required a new grant of authority by the attorney general (which Janet Reno gave, ill-advisedly).

And, no, Mueller’s possible inquiry into Trump’s finances is not at all like Starr going after Clinton’s sex life.

Rosenstein explicitly gave Mueller legal authority to investigate not only the possible links between the Russian government and the Trump campaign but also “any matters that arose or may arise directly from the investigation.” That language is not just boilerplate; it encapsulates basic prosecutorial practice, as detailed above. Were the fishing expedition claim ever somehow to proceed to a federal court, it would be resolved in Mueller’s favor based on this language as well as the standard practice and policy it reflects.

Trump’s pre-2016 financial dealings are, inevitably, a part of the authorized investigation. The red line that Trump has drawn is bogus, and Mueller’s adhering to it, contrary to standard prosecutorial practice, would be a disservice to the American people. In legal terms, the prior financial dealings go to motive, which any prosecutor is entitled to investigate and prove.

Mueller’s investigation, moreover, now has a social function of resolving doubts born of the most bizarre and defensive behavior by Trump, including the drawing of the red line itself.

In the outrageous soap opera that is the Trump presidency, there are darker story lines driven by sinister conduct and lighter ones driven by buffoonery, and we don’t yet know which are which. Perhaps the flirtations with Russia during the campaign were, as Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner would have it, bumbling and inadvertent. But what of the possibility — we must hope it is improbable — that the president is beholden to or compromised by Russian interests?

This isn’t about fishing; it’s about the country’s well-being. If Mueller plumbs the depths and finds nothing, that’s good for Trump and good for the citizenry. And if he finds past unseemly or illegal consort with a hostile power, we need to know that even more.

Harry Litman, a former United States attorney and deputy assistant attorney general, teaches at UCLA Law School and practices law at Constantine Cannon.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.