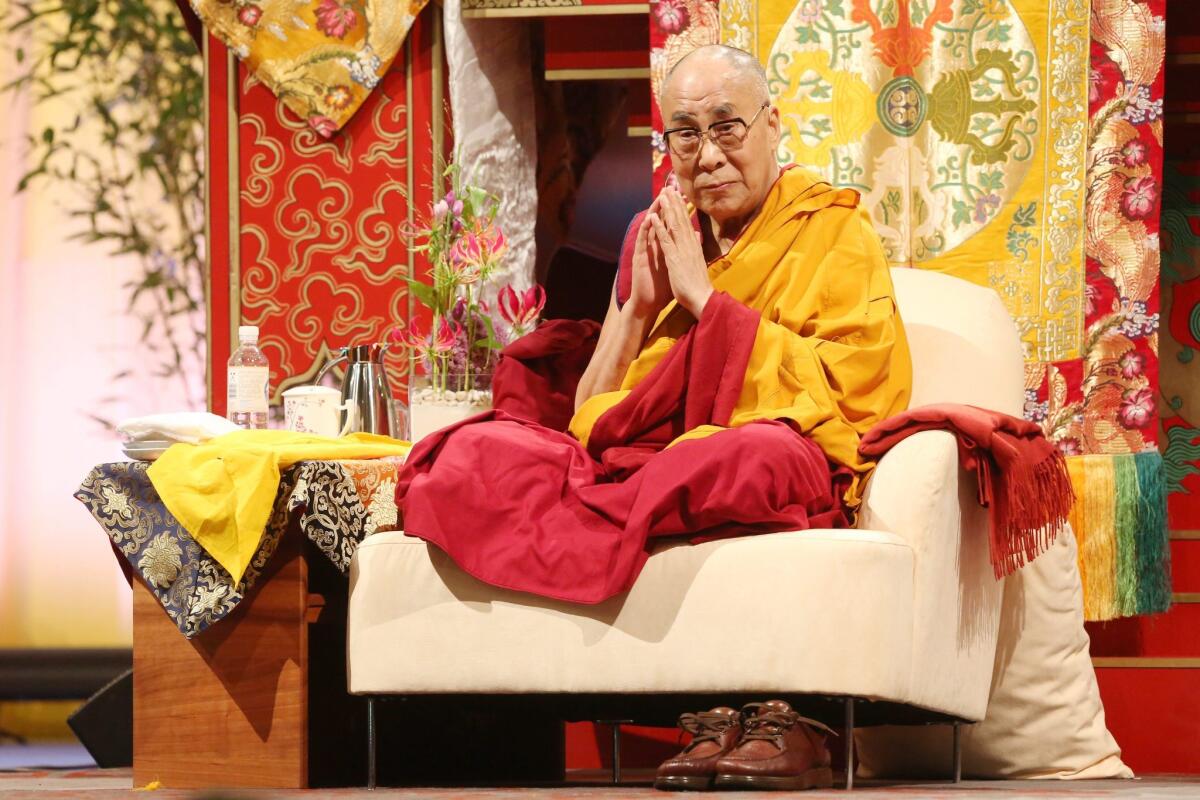

Opinion: If Queen Elizabeth can birth an heir, why can’t the Dalai Lama rebirth one?

Recently, the revered and charismatic Dalai Lama told a German newspaper that there should be no more Dalai Lamas after his death. In other words, this 14th Dalai Lama, who is 79 (and has vowed to live to 113), says he will not be reincarnated as the 15th Dalai Lama. Noting his worldwide popularity, he is quoted in an interview published Sunday in Welt am Sonntag as saying, “If a weak Dalai Lama comes along, then it will disgrace the Dalai Lama.”

The Nobel Peace Prize winner and Tibetan Buddhist spiritual leader would hardly be the first powerful person to worry about legacy in the world left behind. And it can be a melancholy task. Successors are often named or mentored in the shadow of loss — an impending retirement, the frailty of old age, debilitating disease, death. But people who want to ensure the survival of a company or a legacy do it. Steve Jobs, suffering from cancer, groomed Tim Cook to take the reins of Apple after his death. The popular former Los Angeles City Councilman Bill Rosendahl, also fighting cancer, announced in 2012 that he would not seek another term and quickly endorsed his chief of staff, Mike Bonin, who won so handily in the election that he didn’t have to go to a runoff.

Of course, some leave at the top of their game and vitality. Bill Gates relinquished day-to-day control of Microsoft and retired to focus on his philanthropic foundation. His longtime colleague and friend, Steve Ballmer, became chief executive of Microsoft, then he retired and bought the Clippers. Neither man is 60 yet.

This isn’t the first time the Dalai Lama has mused on closing out the lineage of Dalai Lamas that has existed for almost five centuries, according to scholars of Buddhism. And as a highly enlightened being, a bodhisattva, he is believed to control whether and when he is reborn.

And, apparently, this isn’t just about him thinking he’s so personally fabulous. This is more about deciding the job isn’t for this world anymore. As an exiled leader of Tibet who has been at odds with the communist Chinese government that rules in Tibet since he fled that country in 1959, the Dalai Lama may want to avoid China’s exploiting the position after his death. Or it may be that he is worried about any future Dalai Lama maintaining the spiritual integrity and asceticism that the position demands in a modern, excessive world. (He had been schooled in the hermetic world of Tibetan monks before being launched onto the global stage.)

Of course, the metaphysics of Tibetan Buddhism are complicated and unique. But the Dalai Lama’s musings invite comparisons. Would Pope Francis ever declare himself the last pope? Unlikely. But, given his well-publicized penchant for humility, he might stubbornly declare himself the last resident of the papal palace in Castel Gandolfo and sell it off. Would Queen Elizabeth announce that she was the last British monarch? Certainly, there are anti-monarchists and a host of pundits who believe she should do just that. But even as the monarchy is marginalized, Elizabeth sees it as a call to duty (not to mention an engine of tourism).

Legacy can be a fraught thing. Sometimes it means building a monument to oneself, and sometimes it means letting something gracefully expire. But, in all cases, the best legacies are the ones thoughtfully calculated. Whether you’re expecting to be reborn or not.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.