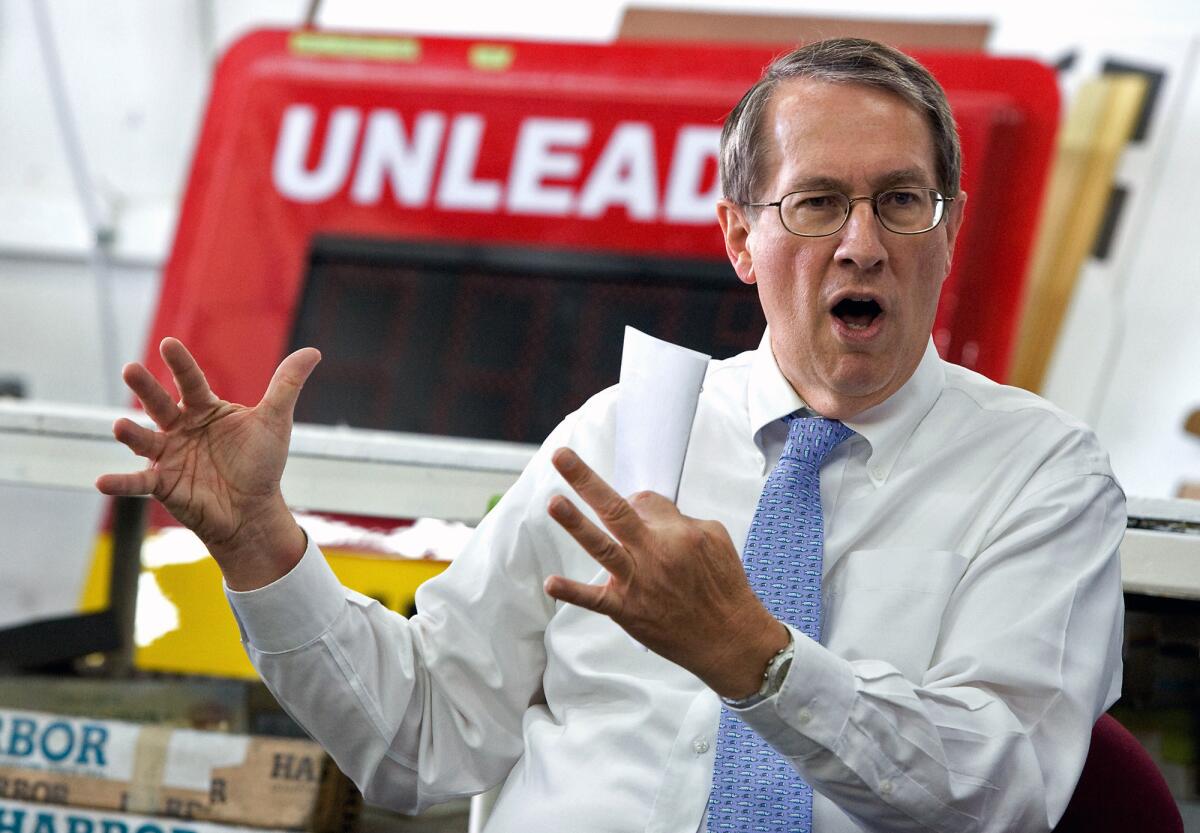

Rep. Goodlatte points online sales tax talks in wrong direction

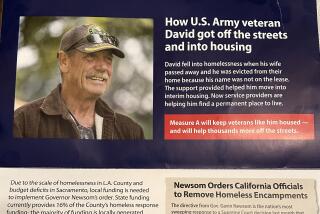

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.) drew cheers from brick-and-mortar retailers this week when he laid out seven principles to “guide discussion” of online sales taxes and “spark creative solutions.” To the retailers, Goodlatte’s announcement opened the door to legislation that would let states require online retailers to collect sales taxes. But Goodlatte’s principles point toward a much different bill than the one the Senate has passed, a bill that offline retailers and state and local governments might not like one bit.

At issue is the exemption that online retailers enjoy from collecting and remitting sales taxes from out-of-state shoppers. Under a 1992 Supreme Court ruling, websites are required to collect sales taxes only from shoppers living in states where the sites have a “nexus,” typically defined as offices or employees.

Shoppers who live in states with a sales tax have to pay it regardless of whether the retailer collects it from them, but most shoppers don’t. Instead, they view online stores as the Internet equivalent of duty-free shops. That gives online retailers a perceived advantage over local retailers, which have no choice but to collect the tax.

The Marketplace Fairness Act (S 743) that the Senate passed in May would let states require online retailers to collect sales taxes even if the retailers have no physical presence there, provided the states meet several conditions. These include making it easier to compute and pay the tax and providing free software that would automate the process.

Goodlatte balked at the Senate bill, saying in June that he didn’t think that measure could pass the House. But he also said that he would explore alternatives that his colleagues could support.

The principles he laid out Wednesday echo the rhetoric used by opponents of the Senate bill, although they don’t shut the door to a bill that would end online retailers’ exemption.

Four of the principles seem noncontroversial. If Congress legislates on Internet sales taxes, Goodlatte wrote, it shouldn’t create new or unique taxes, impose unequal tax burdens on similarly situated businesses, require states to take steps they wouldn’t otherwise take or endanger personal privacy.

The other three are the potential flashpoints.

One, “no regulation without representation,” is a modified version of Heritage Foundation President Jim DeMint’s complaint that the Senate bill forces companies to become tax collectors in states where they have no voice. In Goodlatte’s version, “Those who would bear state taxation, regulation and compliance burdens should have direct recourse to protest unfair, unwise or discriminatory rates and enforcement.”

Taken literally, that’s another way of arguing that businesses shouldn’t be required to collect taxes in states where they can’t cast votes -- which is the status quo. But “direct recourse” doesn’t have to mean access to the ballot box. There are administrative mechanisms that can give online retailers a way to influence rule-making in states where they have customers but no physical presence.

And besides, it’s ridiculous to suggest that out-of-state retailers should have any say at all in local tax rates. They’re not the ones paying the tax; that burden falls on the people who live (and vote) in the communities that impose it.

A second principle calls for simplicity. Writes Goodlatte, “[L]aws should be so simple and compliance so inexpensive and reliable as to render a small business exemption unnecessary.”

Simplicity is in the eye of the beholder. Proponents of the Senate bill argue that tax-computation technology can be plugged into an online retailer’s site, rendering the process as easy as calculating shipping costs. But some small retailers and EBay, a giant amalgamation of individual online sellers, strongly disagree, noting the dizzying array of differences among states and localities in what goods get taxed and what rates get charged.

These critics want to see uniform state rates and exemptions, but that would violate Goodlatte’s principle regarding state sovereignty. But there’s another way to satisfy the simplicity mandate, and that’s embodied by one other Goodlatte principle: “tax competition.” Governments “should be encouraged to compete with one another to keep tax rates low,” Goodlatte wrote, “and American businesses should not be disadvantaged vis-a-vis their foreign competitors.”

This principle alludes to an idea advanced by some libertarians, which is to have the sales tax rate set by the seller’s locale, not the buyer’s. In such an “origin-based” sales tax system, the seller would have to know only one jurisdiction’s rates and remit taxes just to one state, and face the prospect of only one state audit.

That idea is wrongheaded on so many levels, though, it’s hard to know where to start.

Most important, it misconstrues why states impose sales taxes. The point is to spread out the public’s tax burden so that it also falls on consumption, not just labor and investment. That’s one reason sales taxes are imposed on buyers, not sellers, and on goods instead of services. (Note that many of the folks arguing for origin-based taxation also want to replace income taxes and capital-gains levies with consumption taxes because they’re less damaging to economic growth.)

With that in mind, it makes no sense at all for buyers to pay sales taxes to the states where they shop, not the states where they live. Such a shift would rob the buyer’s state of taxes that were intended to support the government services the buyer receives, such as schools, police and street repairs.

Nor would it level the playing field between onine retailers and local stores, unless the website happened to be based in a state with the same sales tax rate. In fact, the change would encourage shoppers and retailers to locate in states with little or no sales tax. That’s great for Oregon but terrible for California.

To proponents of the origin-based system, that’s the point. Their goal is to put pressure on states and cities to race to the bottom on sales tax rates. Yet that would only force states to offset the lost sales taxes with other sources of revenue -- most likely, ones that are more of a drag on growth.

The right approach for conservatives is to embrace online sales tax collection as a way to reduce income taxes, not raise them. That’s the path endorsed by Gov. Scott Walker in Wisconsin, and it’s more sensible than the one Goodlatte seems to be heading down in the House.

ALSO:

Stop playing politics with hunger

No Honey Boo Boos for the French, tant pis

On foreign policy, a consistently inconsistent president

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey and Google+

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.