Opinion: Report the truth -- the whole truth -- on Robin Williams’ death

- Share via

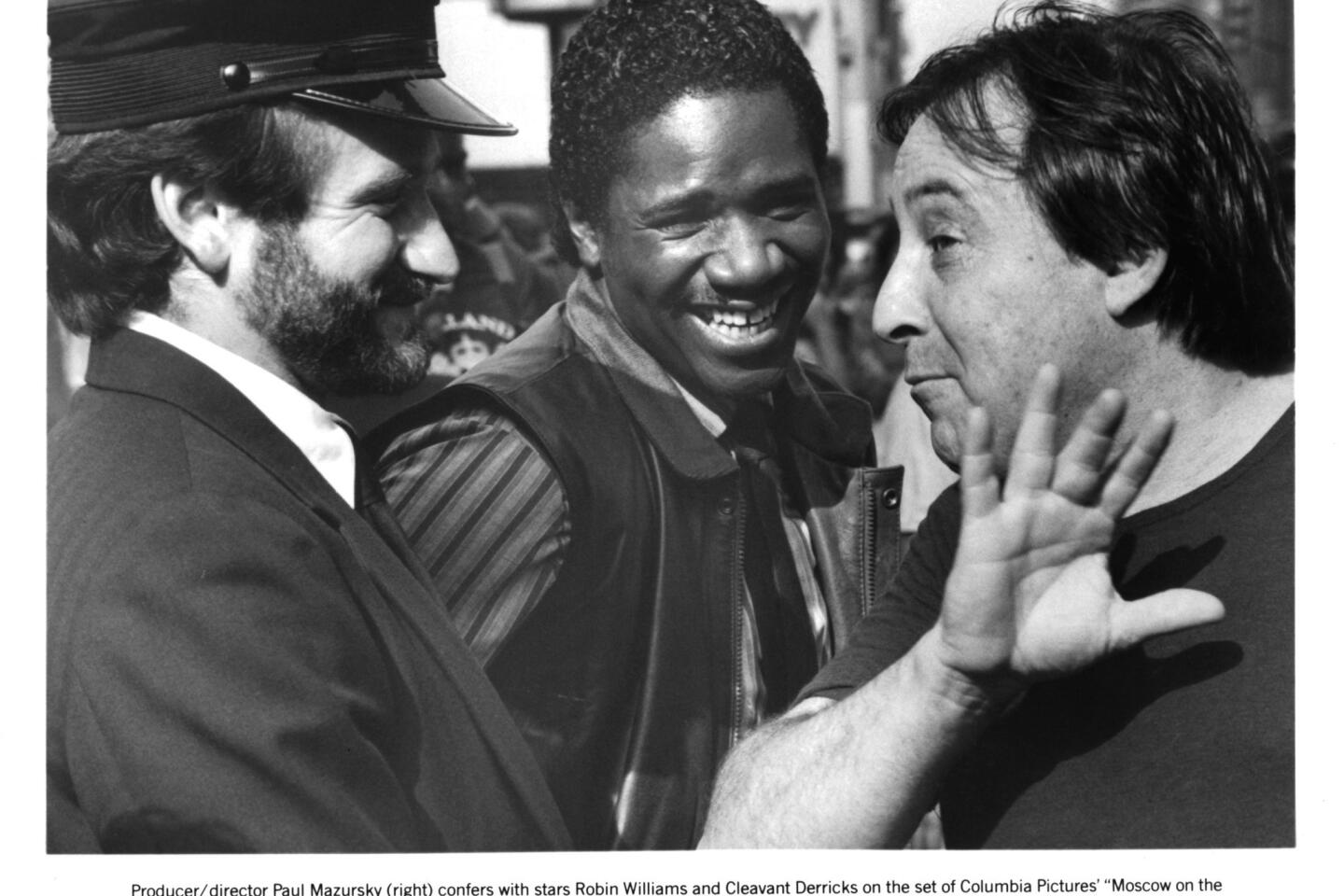

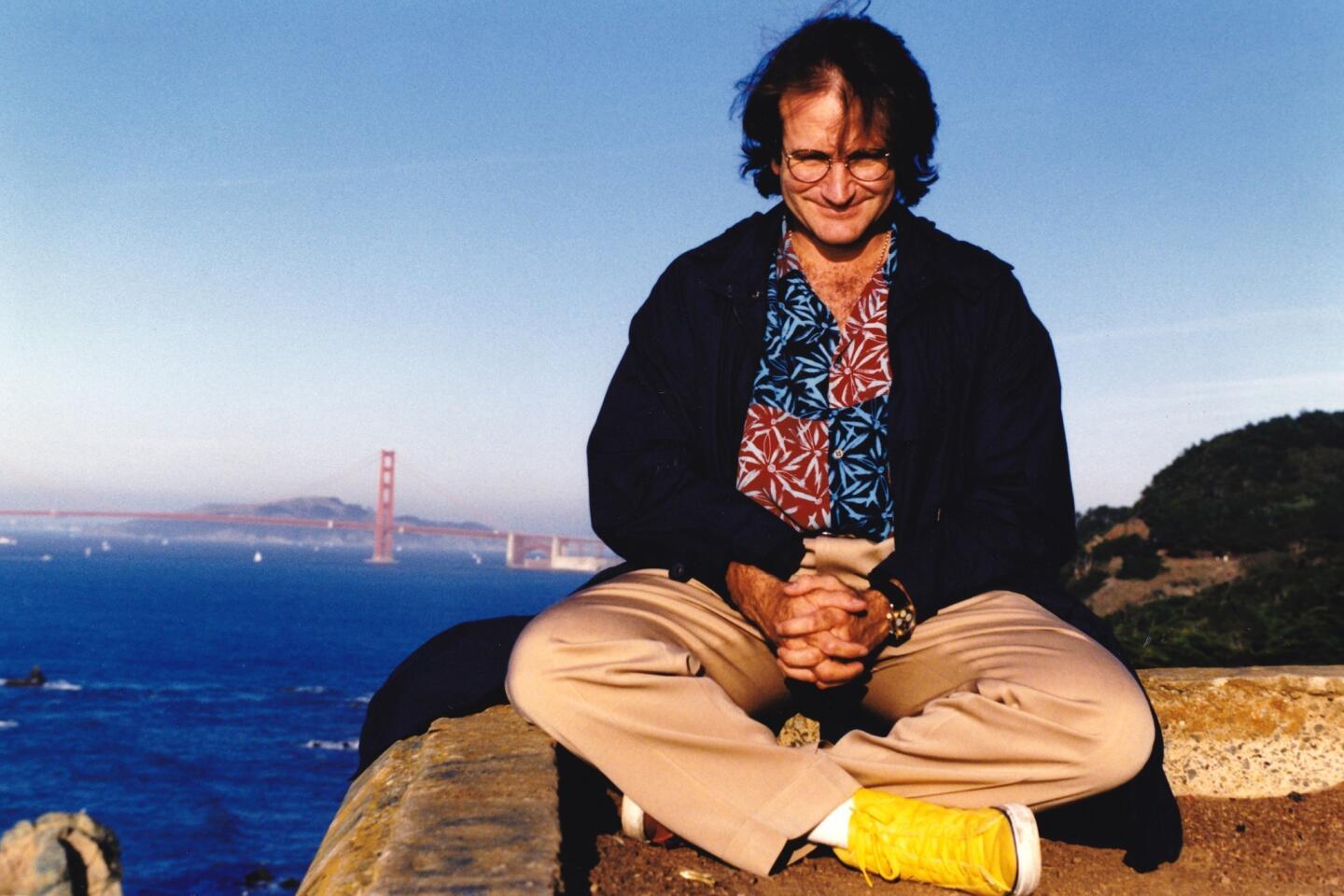

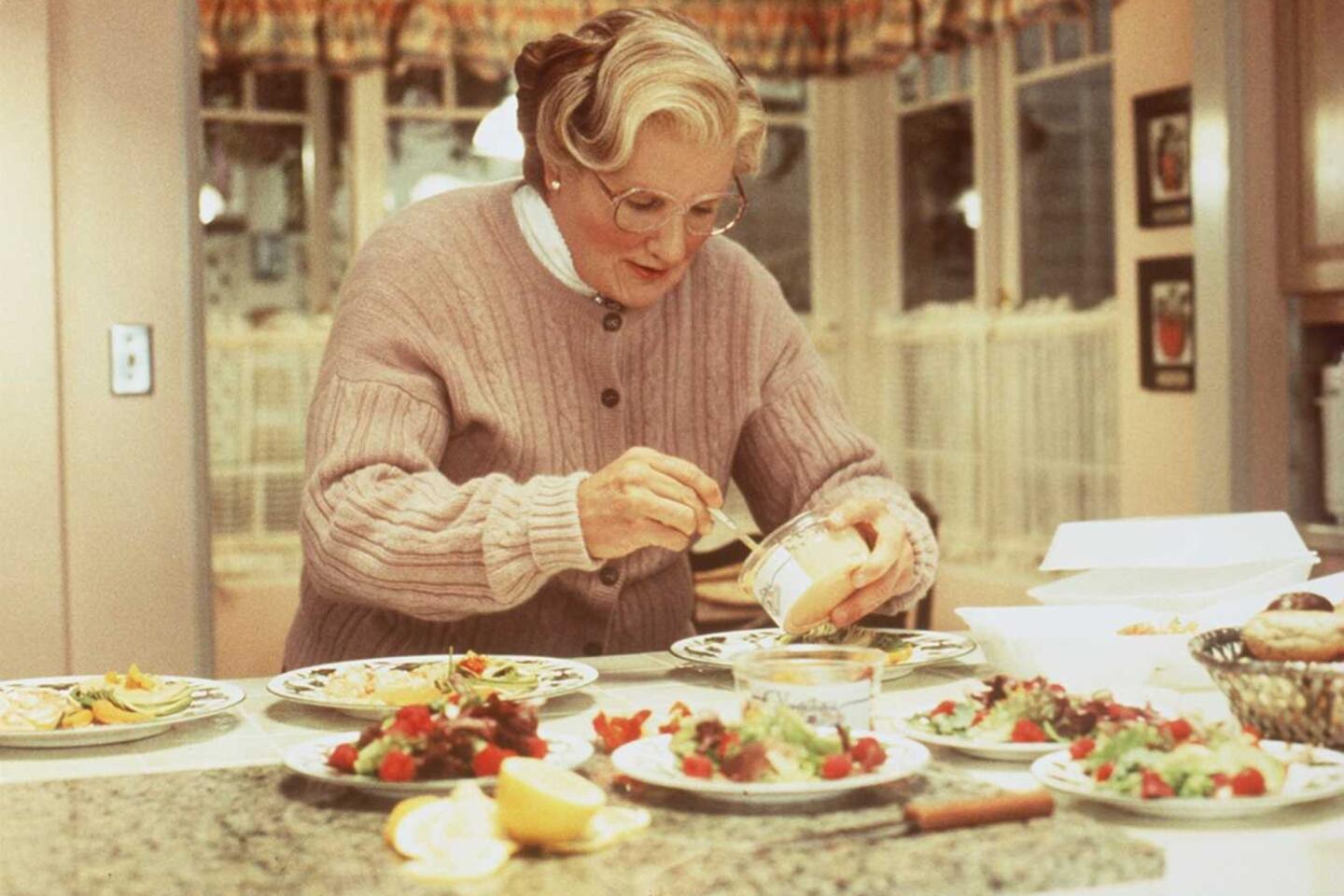

The details of Robin Williams’ apparent suicide aren’t pretty (not that anyone thought they would be): The beloved actor and comedian was reportedly found by his personal assistant suspended just off the ground by a belt wrapped around his neck. Cuts on his wrist suggest he may have attempted to kill himself one way before succeeding at asphyxiation.

You probably wouldn’t know any of this if some enlightened journalists had their way. Those who missed the initial news conference where these details were first reported would have been kept in the dark, because journalists, some people say, don’t have to continue reporting the disturbing facts after they’ve been delivered by the government officials obligated to do so.

Those thinkers are wrong. Journalists’ job is to tell the whole story, and nothing less. I speak from experience.

Many years ago while working as a reporter in a small town, I received an obituary call from a local funeral director. The call was routine in every way but one: The subject of the obit was a young man in his teens. At the suggestion of my editor, I looked into the death and discovered the boy had hanged himself. I added that to the story.

A few hours before the final deadline, I received a phone call. It was the boy’s mother. She had heard I was asking questions about her son. In a voice ragged with grief, she begged me not to print the fact that he had committed suicide. It was a call that would’ve moved a heart of stone.

I had no authority to change the story, so I handed the call to my editor, a woman as kind as she was wise and whose judgment I accepted without reservation. There was no doubt in my mind she would delete the offending sentences. Why not? Some kid kills himself in a small town; who needs to know?

I was shocked to find out I was mistaken. In the gentlest way possible, my editor explained to the grieving mother that the story had to run as it was.

My editor and I debated this decision until after midnight. My argument was that, in such a small story, our sacred duty to tell the whole truth might be harmlessly sacrificed to compassion. Her argument was that this boy’s death was a small story, yes, but part of a bigger story, the story of the county we covered. It was our job -- and an important job -- to tell that story straight.

That my editor was wholly in the right became clear to me a few years later. It was then that county and state authorities discovered that, in fact, there had been a growing plague of teenage suicides in that area, starting right about that time. I can’t say that the small obituary we ran directly contributed to that discovery. I only know we told our readers the whole truth about what turned out to be an important incident in their neighborhood. We did our job, in other words, and it was the right thing to do.

Robin Williams once made me laugh so hard I literally fell off the sofa in my TV room. It is deeply unpleasant to picture him dying the way he did.

The hive mind of the Twitterverse was outraged by the reporting of those details. Al Tompkins of the media watchdog group Poynter told USA Today that “journalists don’t have the obligation to report that information over and over again in that level of detail.”

Tompkins is wrong: The manner of Williams’ death is public information. Journalists should report it as long as it remains of interest to the public.

It is not a journalist’s job to protect us from the ugly facts. Neither is it his job to protect the sensitive from the painful truth or anyone, really, from anything.

In fact, speaking more broadly, it is not a journalist’s job to make the world a better place, to ensure our right thinking, or to defend the virtuous politicians that sophisticates like himself voted for while excoriating the evildoers elected by those country rubes on the other side. It is not his job to do good or be kind or be wise. The idea that any of this is a journalist’s job is a fallacy that seems to have infected the trade in the 1970s, when idealistic highbrows began to replace the Janes and Joes who knew a good story when they heard one.

Because that’s the journalist’s job: the story. His only job: to tell the whole story straight.

In the greater scheme of things, Williams’ suicide is a small story, but it is part of a bigger story: the story of our country and our world. That story unfolds only slowly, and no one knows what wisdom it will ultimately reveal. The best we can do is tell each chapter whole and true, without piety or fear or favor.

The best we can do is journalism.

Andrew Klavan’s latest book for young adults is “MindWar.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.