Opinion: The Buffett Rule’s threat to Sen. Warren’s student loan refi bill

- Share via

If you had an idea that you wanted to push through Congress, would you hitch it to a controversial tax proposal that had no chance of becoming law?

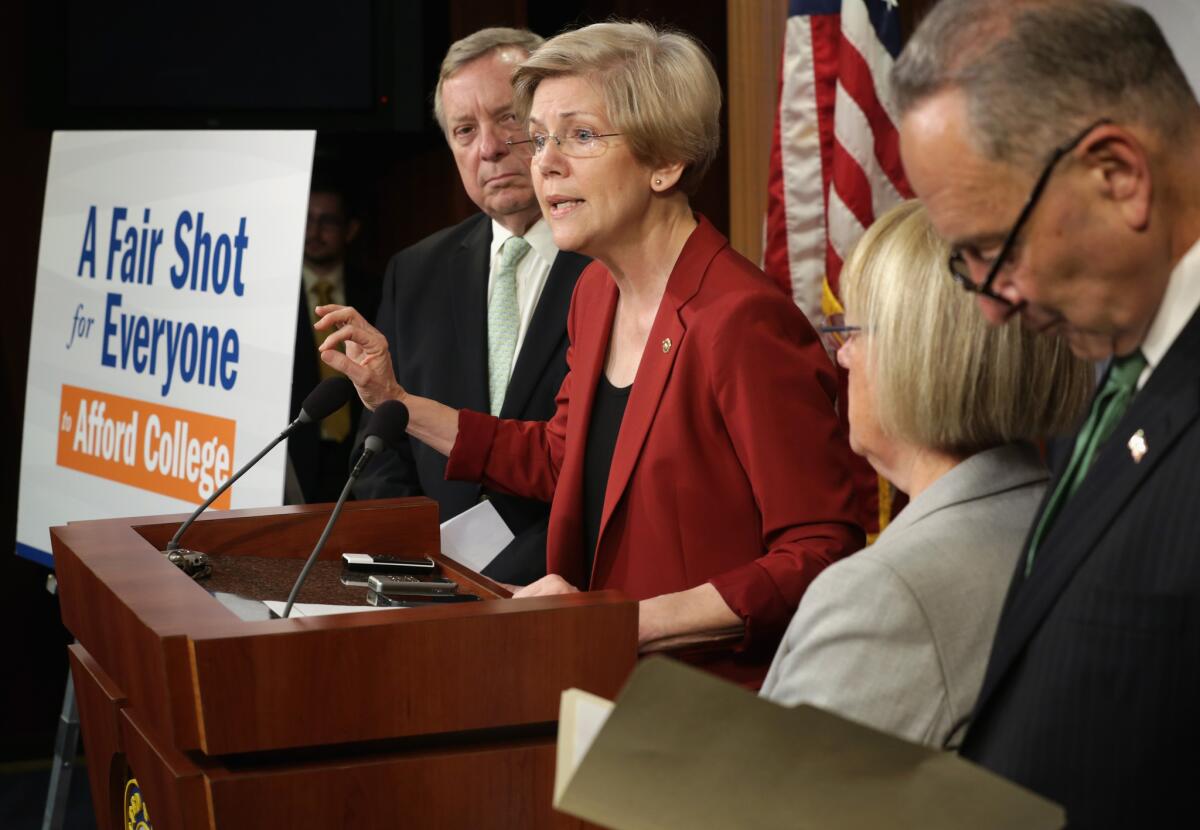

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) wants the federal government to make it easier for people with student loan debt to refinance into lower-interest federal loans. The problem for Warren is that, as the Congressional Budget Office observed, the lower interest rates of refinanced federal loans mean that “the federal government would receive less interest income over the life of the new loans, which would make those loans and loan guarantees more costly” to the Treasury. By the CBO’s estimate, S 2292 (an earlier version of Warren’s proposal) would cost $55.6 billion.

To fill that hole, Warren proposed to enact the so-called Buffett Rule, a new minimum tax named after the billionaire Berkshire Hathaway honcho that President Obama proposed in 2011. But the provision is such a poison pill, you have to wonder whether Warren sees student loan debt as a problem to be solved or a campaign issue to be seized.

It certainly looks more like the latter than the former. Democrats have latched onto student loan debt as one of the “fairness” issues they hope will sustain their congressional candidates in November, alongside such things as raising the minimum wage, extending federal unemployment benefits and promoting equal pay for women. It’s also telling that the measure had 39 cosponsors as of Monday, none of them Republican.

The Buffett Rule would impose a new minimum tax on anyone making more than $1 million a year; when fully phased in (for incomes above $2 million), it would ensure that a household paid at least 30% of its earnings in income, alternative minimum, payroll and Medicare taxes. In 2012, Democrats called it the Paying a Fair Share Act, which is a good distillation of the argument behind the proposal.

I’m not a fan. The reason people like Warren Buffett pay a lower percentage of their income in taxes than the average working stiff is that they make most of their money off of their investments, whose capital gains are taxed at a lower rate than wages and salaries. The Buffett Rule would wipe out that preference for the portion of the country that benefits most from it, without bothering to debate whether the tax break is good or bad for the economy.

The preference for capital gains is more the norm than the exception. After eliminating it in the Tax Reform Act of 1986, Congress voted three times in the past quarter-century to restore and increase the tax break. As a result, the effective tax rate on capital gains is comparatively low -- less than 14%, according to the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center.

Lawmakers have long hewed to the belief that applying a lower tax rate to capital gains encourages people to save (which Americans historically are bad at doing) and invest (which helps the economy grow). The evidence to support this belief is thin, yet most countries in the developed world provide a tax break for such gains.

As with many preferences in the tax code, most of the benefits from the lower rate on capital gains flow to higher-income households. The Tax Policy Center estimates that 94% of the savings go to those earning more than $200,000, and 76% go to those with incomes over $1 million.

Congress should debate whether the preference for capital gains is worth preserving, in whole or in part. It should do so, however, as part of a larger discussion about how to overhaul and simplify the tax code. The Buffett Rule, by contrast, would add even more complexity to a tax code suffocating in it.

And even if you think the Buffett Rule is the best thing since the temporary payroll tax holiday, you have to concede that it can’t make it past a Senate GOP filibuster, let alone win approval from the GOP-majority House. Some Republicans have said they’re willing to consider higher tax revenues in the context of a tax reform that lowers rates and broadens the base. But raising rates to pay for a new federal program? Not happening.

Granted, Warren may have included the Buffett Rule in her student loan bill simply as the starting point of negotiations. We’ll find out whether that’s the case Wednesday, when the Senate is expected to vote on a motion to begin debate on the bill -- and Republicans are expected to block it. If this measure is simply campaign fodder for Warren and her fellow Democrats, they’ll drop it at that point, having achieved all they ever intended to with the bill. Otherwise, they’ll find a way to pay for the bill that Republicans can support.

Warren, for one, said she’s ready and willing to negotiate when she introduced the current version of the bill (S 2432) last week. “I am encouraged by the fact that some Republicans have also come forward to say they are open to considering a refinancing proposal,” she said. “I want to be clear: This should not be a partisan issue. I am eager to work with any of my colleagues regardless of party who believe that we need to do something about this growing debt crisis. If they have issues with the proposal, if they want to suggest different offsets or policy changes, they should bring their ideas forward. We are ready to hear them.”

Warren was being disingenuous there, because she couldn’t help but know that Republicans “have issues with” the Buffett Rule. She could help her own cause by having an alternate way to pay for the bill ready. She’ll need it.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.