Op-Ed: Why California needs to institute a ‘student borrower bill of rights’

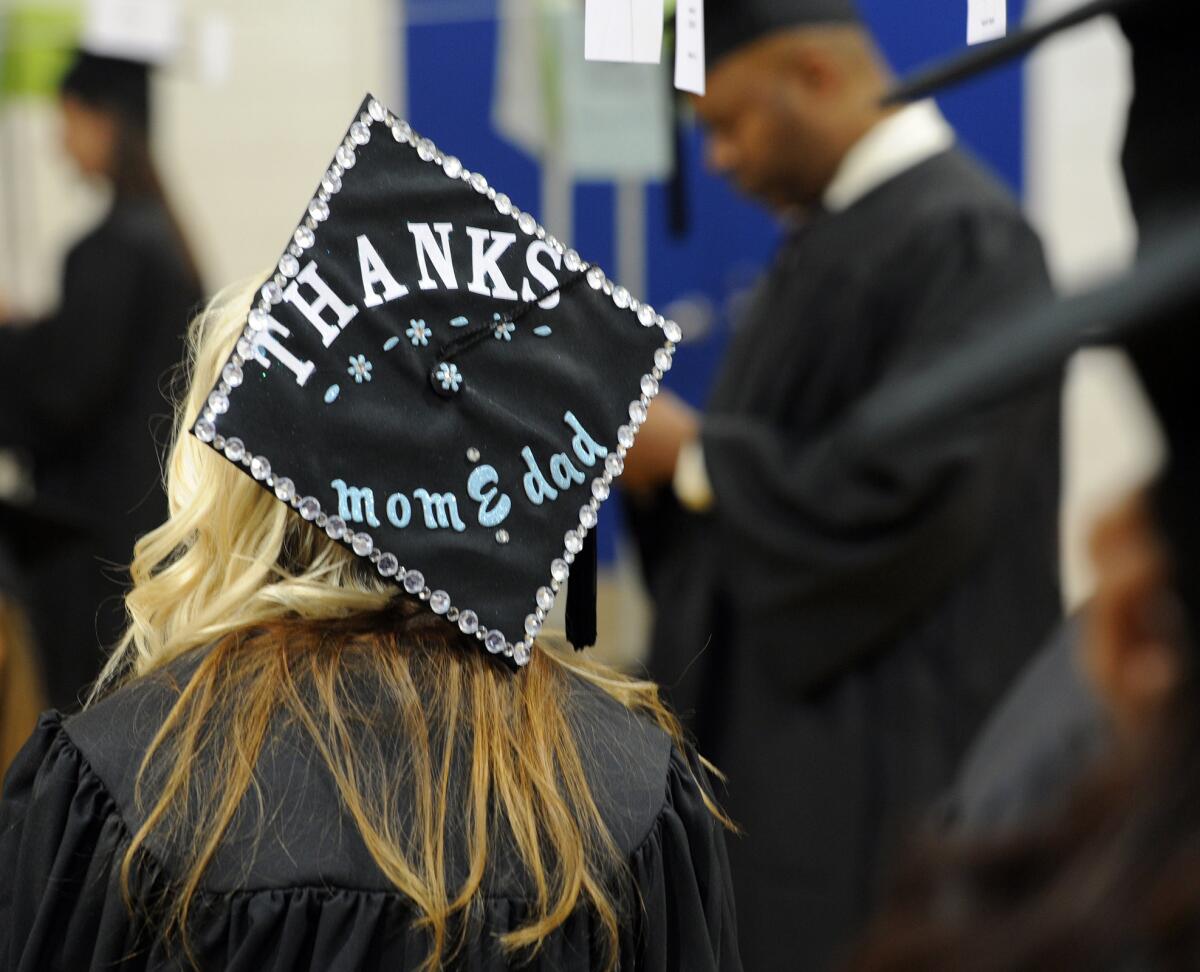

Like a majority of graduates, Andrea Sandoval earned a college degree, in 2008 from USC, that left her with a mountain of debt. A first-generation immigrant from Costa Rica, she landed a job at the Department of Veterans Affairs in Los Angeles and found out about a federal program for public service employees that was supposed to eliminate her debt after she made 120 on-time monthly payments.

Six years — and about 72 payments — later, Sandoval was shocked to learn that none of those payments would count toward the 120 she needed to earn loan forgiveness. It turned out she had enrolled in the wrong repayment plan, even though her loan servicer had assured her she was in the right one.

Loan servicing failures like these cost borrowers time and money, and they are common. As a student loan borrower, I’ve been subject to servicer errors and delays that added interest to my loans and grew the size of my debts.

Several million Californians have education debt to pay off but too often get tripped up by a terribly complex repayment system and shoddy treatment by loan servicers. To make matters worse, the Department of Education under Secretary Betsy DeVos has refused to set loan servicing standards to help struggling student borrowers.

Californians who are repaying debt could finally get some relief if state lawmakers pass Assembly Bill 376, also known as the “student borrower bill of rights,” in the coming weeks. The Assembly approved the proposal in May, and it will face a critical vote on the Senate floor sometime after the Legislature returns in mid-August.

Consumer Reports, the organization I work for, chose to co-sponsor the bill because we believe that setting clear rules of the road for servicers will help ensure that borrowers are treated fairly and can access important rights they have been promised, such as the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program.

Taking out loans for college is inevitable for most students and their families, and new graduates typically have tens of thousands of dollars in education debt. An estimated 3.8 million Californians hold more than $141 billion in outstanding college debt, with an average balance of about $37,500. Over half a million of them have fallen behind on repaying their loans.

Student loan servicers are the main point of contact for borrowers — taking payments, keeping account records and handling requests. In recent years, these companies have been the target of numerous lawsuits alleging abusive practices and mistreatment of borrowers.

Last year, California Atty. Gen. Xavier Beccera sued Navient, one of the nation’s largest loan servicers, for steering vulnerable student borrowers into more expensive repayment plans and failing to disclose how they could qualify for more affordable payment options, among other abuses.

An analysis by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that student borrowers often encounter paperwork processing delays and inconsistent instructions from servicers that make it more difficult for them to manage their debt.

This year, the independent inspector general’s office of the Department of Education issued a report documenting similar abuses and found that the agency failed to hold loan servicers accountable when they treated borrowers unfairly.

Unlike consumers with mortgages and credit cards, student loan borrowers have few protections when interacting with the companies that service their loans. Though student loan servicers are generally prohibited from engaging in unfair or deceptive practices, like any other business in California, they are not subject to industry-specific standards.

The bill before the California Legislature would change that by creating standards that require servicers to apply payments in a way that minimizes extra interest charges or fees, improve record-keeping and train staff to provide borrowers with accurate information about their repayment options. It would ban “abusive” student loan practices that take advantage of borrowers’ confusion over the loan repayment process and establish a student loan advocate to review borrower complaints, gather data and issue reports to the state Legislature.

In the end, USC graduate Sandoval was able to take advantage of the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program after Congress voted to enable borrowers in the wrong repayment plan to apply for it. The payments she had already made would count toward the 120-payment requirement.

Given the Department of Education’s failure to hold loan servicers accountable, student borrowers need states like California to fill the void. The student borrower bill of rights would finally give them the protection they deserve.

Suzanne Martindale is a senior policy counsel and western states legislative manager for Consumer Reports.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.