Opinion: The government’s refusal to vaccinate migrants in detention puts us all at risk.

Between 2003 and 2007, the prospect of an ultra-lethal influenza pandemic had public health officials around the world worried. The vast chicken farms of Asia had seen outbreaks of a highly pathogenic H5N1 avian flu, and a handful of people had come down with it as well. If the virus evolved to become easily transmitted to humans, experts warned, as many as 350 million people could die.

But chicken flu, fortunately, remained stubbornly chicken flu.

We did get a pandemic, though not an especially lethal one, in 2009, of H1N1 influenza, which likely emerged from a giant pig farm in Mexico. Recent research suggests that swine flu is more likely to produce a pandemic than bird flu, possibly because people are more like pigs than birds.

But the best incubators for virulent human disease are humans. As evolutionary biologist Paul Ewald, now of the University of Louisville, argued in his 1993 book “Evolution of Infectious Disease,” the infamous 1918 influenza strain, which killed 20 million to 50 million people, became so deadly virulent in the packed trenches, trucks, ships and trains of the Western Front. There the germ could jump easily from soldier to soldier, removing any need for the virus to remain mild enough to keep its host walking around to serve as a viral delivery system.

Tight concentrations of animals or humans create ideal conditions for influenza strains to grow deadlier. That’s why industrial chicken and pig farms can brew such deadly chicken and pig disease, and that’s why we should be very worried about the migrant detention camps along the southern U.S. border.

It isn’t just that the conditions in these camps, according to reports from people who have visited them, are appallingly cruel, or that three children detained in the camps have died of influenza, or that another outbreak, mumps, has already infected 898 adult migrants and 33 staff members. It’s that the conditions in the migrant camps are exactly what are needed to create a disease factory, where deadly influenza strains can evolve and flourish.

Crowding is necessary for a disease factory, and these camps are crowded. Officials from the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of the Inspector General visited five camps in the Rio Grande Valley in June. Facilities built to house 40 teenage boys housed 51 adult women; 71 men were held in facilities meant for 40. Some men were kept for a week in rooms with standing room only. And hundreds of migrants, often without access to showers, soap, toothbrushes or clean clothes, are kept for far longer than the 72 hours mandated by U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s own regulations.

The presence of lots of people, though, is not enough, as virologist Earl Brown, emeritus professor of the University of Ottawa, points out. Refugee camps in Syria, Yemen, Kenya and elsewhere haven’t produced pandemics of virulent disease, Brown noted in an email. Disease evolution isn’t prompted merely by ordinary crowding, even in refugee camps. Disease factories require conditions where people are packed in tightly and inescapably, as in trench warfare or factory farming. In such situations, the brakes to virulence are off.

An official at CBP explained by email that people with respiratory illnesses are taken out of the general population and housed in separate rooms. “We are going to take necessary precautions to see that they don’t infect anyone else,” he wrote, noting that there are 200 medical personnel working in the camps.

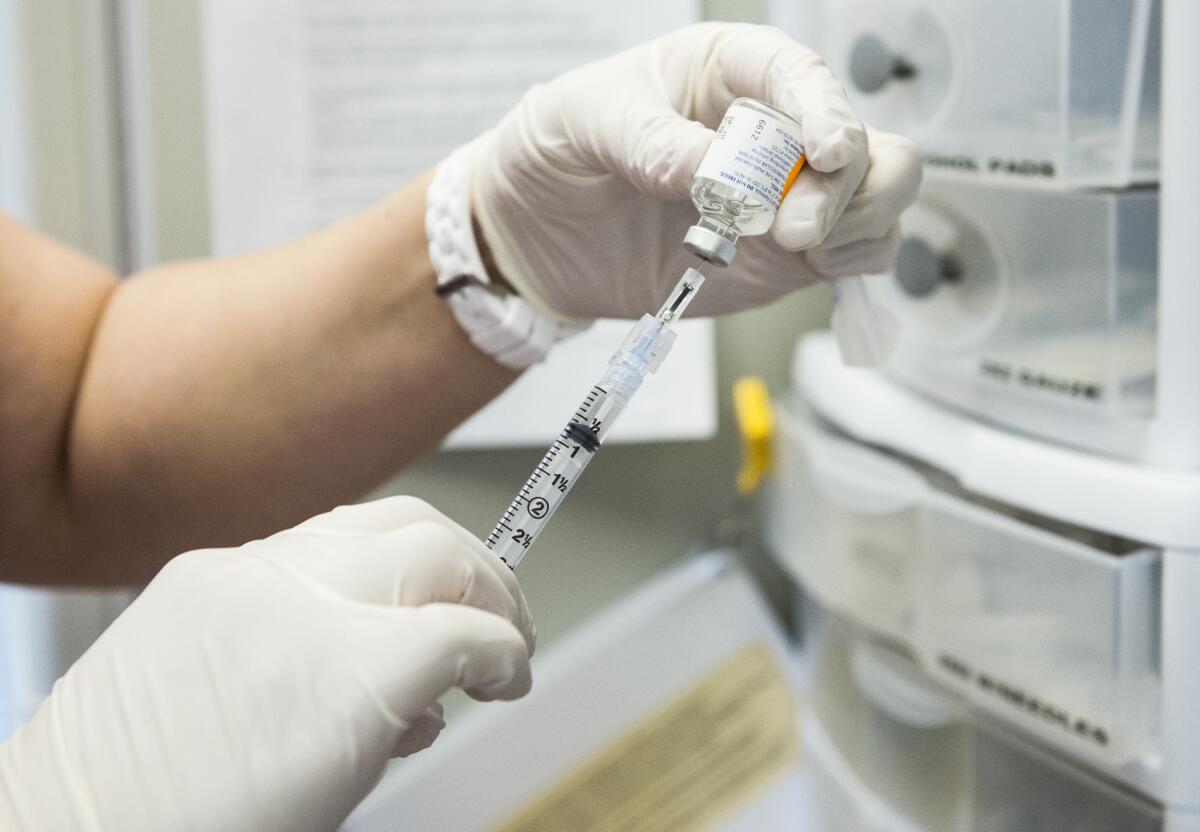

But CBP has said it will not take the single most important step in preventing a disease factory in its migrant holding facilities: vaccination. If the virus does enter the camps, through a detained migrant or staff member during the coming influenza season, all bets are off. Disease factory conditions exist, and there are no immediate plans to ameliorate them.

Six children have already died in CBP custody, three of them of influenza. “We don’t have the capability to handle the masses that are coming across at this time,” the CBP official said in an interview, adding that “Congress needs to fix this.”

Ruby Powers, a Houston-based immigration attorney who does pro bono work with detained migrants, puts it this way: “You’re talking about a group of people who are confined to quarters who don’t have control of their health, who are dependent solely on the U.S. for their medical care, so it if it’s generally considered a health advisory to have a flu shot, and it’s not being provided at this juncture — it seems blatantly irresponsible.”

You have to ask, are people who may be indifferent to the fate of migrants going to be equally indifferent if an unusually severe flu influenza breaks out of the camps into the general population?

It is something the Trump administration may want to think about.

Wendy Orent is the author of “Plague: The Mysterious Past and Terrifying Future of the World’s Most Dangerous Disease” and “Ticked: The Battle Over Lyme Disease in the South.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.