Editorial: Bad policies are turning colleges into COVID-19 hotbeds

Brigham Young University’s Idaho campus is investigating reports that its students have been intentionally exposing themselves to the new coronavirus in hopes that after the illness passes their blood will have money-making antibodies.

Plasma donation centers are paying top dollar for so-called convalescent plasma, which is being studied as a possible treatment for COVID-19. It’s helpful to scientists to have the plasma available, but that shouldn’t come at the expense of people endangering themselves and those around them.

This is just one example of how colleges have become the focal point of rising infection rates this fall. And though campus outbreaks have resulted in only a couple of deaths so far, there are signs of infections spreading through small college towns — and fears about what will happen when students return home for the holidays.

The college COVID situation isn’t like those at K-12 schools, where even outbreaks of just two or three people have been fairly uncommon. At individual colleges and universities, the numbers of cases have been in the dozens, the hundreds and, in some cases, the thousands. Depending on who’s counting and how, the total number of students and staff infected at colleges and universities so far this fall is somewhere between 130,000 and 170,000.

After decades of inability to curb binge drinking and dangerous fraternity hazing, it’s almost quaint that college administrators thought they would get students to hunker down in solo dorm rooms and don a mask before socializing at careful six-foot distances.

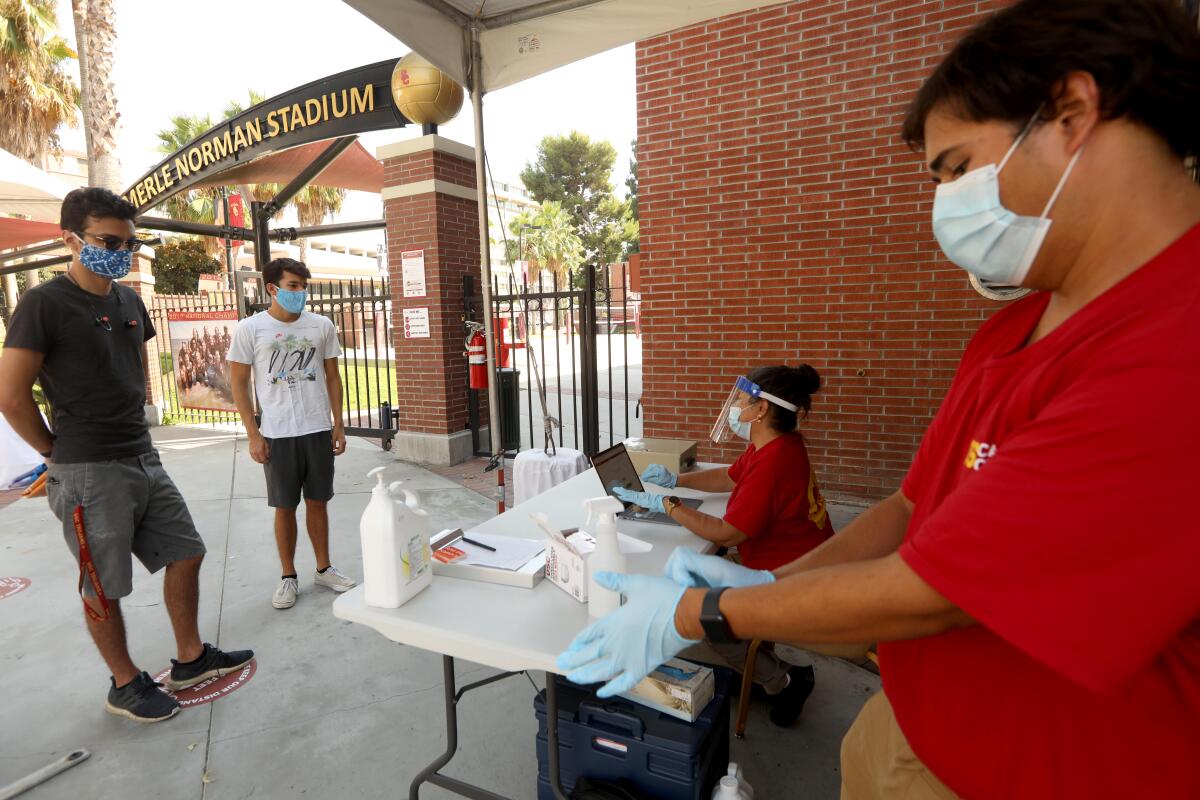

There’s plenty of blame to go around, including schools that based their decisions on economics, not safety, and that haven’t been regularly testing and tracing. To say that students at many schools haven’t followed safety rules would be the COVID understatement of the last couple of months. They came for college life, which means parties, often with drinking that loosens caution. Even at schools that held all their classes online, such as UC Santa Barbara and USC, some students returned to their off-campus rentals, either because they couldn’t get out of their leases or they wanted to see their friends. USC, which is on remote learning this fall, nonetheless experienced more than 1,000 cases from students living just off campus.

And in at least one case, a university leader set such a bad example that he was chided by his own students. John Jenkins, president of the University of Notre Dame, tested positive after attending the now-notorious Rose Garden reception last month for Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett, shaking hands, wearing no mask and sitting close to others.

In the absence of leadership from the federal government ― and funding that would help preserve colleges and their students’ educations ― the schools were trapped into iffy decision-making. Students want to go to campus because, for many, college is as much about new friendships, sports and the first years of living away from home as it is about learning. Those who are willing to attend remotely seek steep discounts because of the thinner experience; colleges respond accurately that it’s actually costing them more to teach remotely because of technology requirements and other needs. And they’re unable to bring in revenue from dormitories that stand empty, another blow to the budget.

More students than usual are taking gap years, hoping for an in-person college experience later on, but this creates its own problems. If too many students defer admission, schools will have to restrict the number of students admitted the following year. As a result, some colleges aren’t reserving slots for these students.

There are strange bright spots to this scenario. Despite all the illness this fall, only a handful of cases have required hospitalization. There are signs that some outbreaks burn themselves out, with a steep rise followed by very few cases. Studies have found that reinfection is possible but very rare.

Yet the potential for danger is there. COVID-19 rates have risen sharply in small towns containing good-sized universities. And come the holidays, students will return to families and neighborhoods with vulnerable older people during a time of celebrations ― and shorter, colder days, when more people gather indoors, where the virus is more easily spread.

Much of this could have been avoided if colleges had thought to do more than just test students and impose rules that everyone knew weren’t going to be followed. They could have pressured landlords to allow students to break leases with a partial payment and offered incentives, such as a tuition discount or a quicker path to graduation, to students who agreed not to move near the campus. Additional options: Imposing modest pay cuts on higher-salaried employees and accepting more students off wait lists to boost enrollment.

We all have to recognize that the pandemic isn’t going to just disappear and allow normal life to return anytime soon. Colleges, along with everyone else, are in this for the long term. Schools need more federal relief, but they also should stop assuming that relief can substitute for systemic changes in how they are run. Planning should start now for rethinking the college experience for the next couple of years, and perhaps beyond. But for right now: Don’t let the kids go home without a COVID-19 test.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.