Op-Ed: ‘CARE Court’ is no solution for unhoused people in California

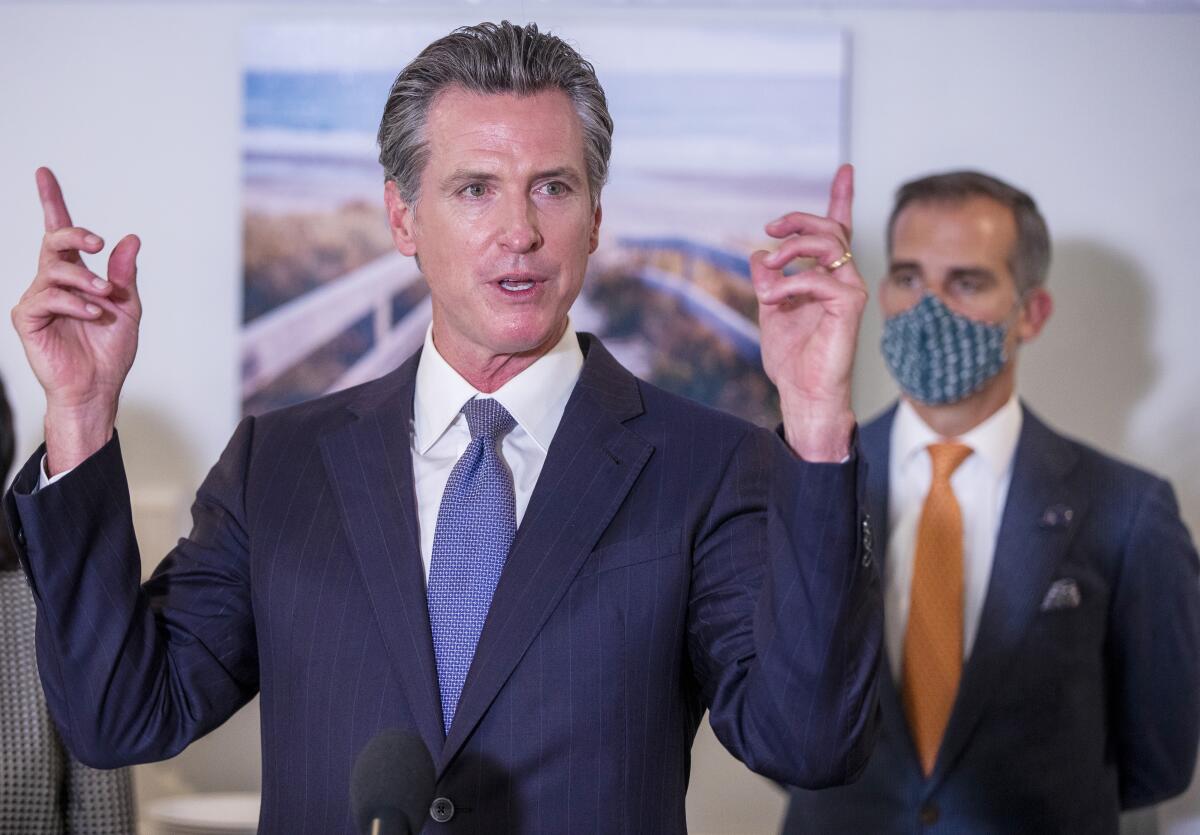

In March, Gov. Gavin Newsom unveiled a proposed framework to force some people living with mental health conditions to undergo treatment under court order. On Wednesday the California Senate passed a bill to enact this framework and create the deceptively named Community Assistance Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Court. There is nothing empowering about involuntary treatment.

CARE Court targets unhoused people throughout the state, but can apply to housed people as well. Though promoted as applying to a narrow category of people with severe mental health conditions, the program’s criteria are highly subjective. Adults diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum or “other psychotic disorder” whom a judge finds lacking in judgment or likely to relapse could fall under its jurisdiction, according to the bill, which now heads to the Assembly.

The state urgently needs more readily available voluntary treatment for all Californians with mental health conditions, and there is a desperate shortage of affordable supportive housing. But CARE Court will not provide either resource. Instead, it reshuffles existing funding for housing and healthcare, while building an expensive system of state control over fundamental life decisions.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed budget includes $65 million for his CARE Court proposal, but major funding questions remain.

Although CARE Court proponents use the language of “empowerment” and “self-determination,” the proposed system is not voluntary. A person enters the court’s jurisdiction because someone else — such as an adult family member, roommate, police officer or behavioral health worker — files a petition to the court. If the judge finds that the petition adequately asserts that the person meets vaguely defined CARE Court criteria, then that person is forced into a convoluted process in which they must negotiate the terms of their required treatment with the county behavioral health agency.

If the person disagrees with the agency, then the court orders that same agency to evaluate the individual, absent an agreement to use an existing evaluation made in the past 30 days. This process gives the agency control over the evaluation. The judge considers the evaluation, alongside other evidence, and can then order the creation of a treatment plan that the person either accepts or is ordered by the court to accept. The plan can last up to one year, and the judge can extend it for another year if they determine the person failed to comply.

In selling CARE Court, officials are using tragic stories of families who struggled to get mental health treatment for their loved ones, many of whom are unhoused. However, the proposal does not invest new money into making treatment or other community-based responses more widely available. It does not add resources to develop permanent safe and supportive housing, critical to helping unhoused people with mental health conditions get off the streets.

Instead, it relies on existing, largely inadequate housing programs and funding already allocated for voluntary mental health services. The proposed new funding — about $65 million in the governor’s revised budget — will pay for new court infrastructure, including hiring personnel and training judges.

State officials have misleadingly promoted CARE Court as “diversion to prevent more restrictive conservatorships or incarceration.” In fact, people can be compelled into CARE Court without being accused of a crime or qualifying for conservatorship. The CARE plans are enforceable court orders, which can include coerced medication as well as submission to treatment modes not chosen by the person who must comply.

Those who do not comply may be set on the path to conservatorships, which allow the state to lock people up and rob them of their autonomy.

One-third of criminal defendants who come through my courtroom have been found to have a mental illness. Instead of incarceration, they need treatment.

Under international human rights standards, treatment should be based on the will and preferences of the person concerned. Housing or disability status does not rob a person of their legal capacity or right to personal autonomy. The expansive, involuntary CARE Court process denies these rights.

Behavioral health providers say involuntary treatment is ineffective and can further traumatize and harm vulnerable people while hampering their recovery efforts. Studies of court-ordered drug treatment have linked coerced treatment with increased overdoses and relapses compared to voluntary treatment.

The potential for abuse in this program is astounding. A family member could wield a petition or the threat of a petition as a weapon of control over a less powerful family member. Police and other officials could use petitions as tools to remove unhoused people from public spaces, without helping them find housing. Because CARE Court would not require an arrest or hospitalization to initiate court control, it could be used to funnel law-abiding unhoused people into shelter and interim housing that often imposes jail-like conditions and rules.

Disturbingly, CARE Court would place Black and brown Californians disproportionately under more court control because discrimination in housing, lending, employment and healthcare has pushed these groups into high rates of houselessness — and because mental health professionals have disproportionately overdiagnosed these groups with schizophrenia and psychotic disorders.

California needs to invest more resources in voluntary, community-based options such as permanent supportive housing and peer-led programs to help unhoused people with mental health disabilities and problematic substance use. Until these resources are made available separate from punitive court processes, Californians cannot expect to see real change.

Olivia Ensign is a senior advocate and John Raphling is a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.