In Orange County, land of reinvention, even its conservative politics is changing

In La Palma Park Stadium in Anaheim, a month before the Bay of Pigs invasion, 7,500 students and parents skipped school or work and gathered to learn about communist plans to take over the United States.

“Right now, we have a 50-50 chance of defeating the communist threat,” Herbert Philbrick, a former FBI agent, told the crowd on March 8, 1961. “Each day our chances grow less.”

Walter Knott, of berry-farm fame, sponsored the five-day “Christian Anti-Communist School” to help Orange County see the world that he saw, one where big government and liberalism led to Soviet domination.

The message stuck. Within the decade, Orange County would have 38 chapters of the conspiracy-minded, ultra-right-wing John Birch Society, which called Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower a “communist tool.” Knott and actor John Wayne were members, as was the county’s congressman.

The rightward mobilization during the suburban explosion of the 1960s gave Orange County a national reputation for hard-line conservatism with a crackpot edge — “nut country,” in the words of Fortune magazine.

The county’s deep pockets funded right-wing candidates and movements throughout the nation. At home it spawned popular but ultimately doomed measures such as the Briggs Initiative in 1978 to ban gays and lesbians from working in public schools, and Proposition 187 in 1994, which would have denied public services to immigrants in the country illegally.

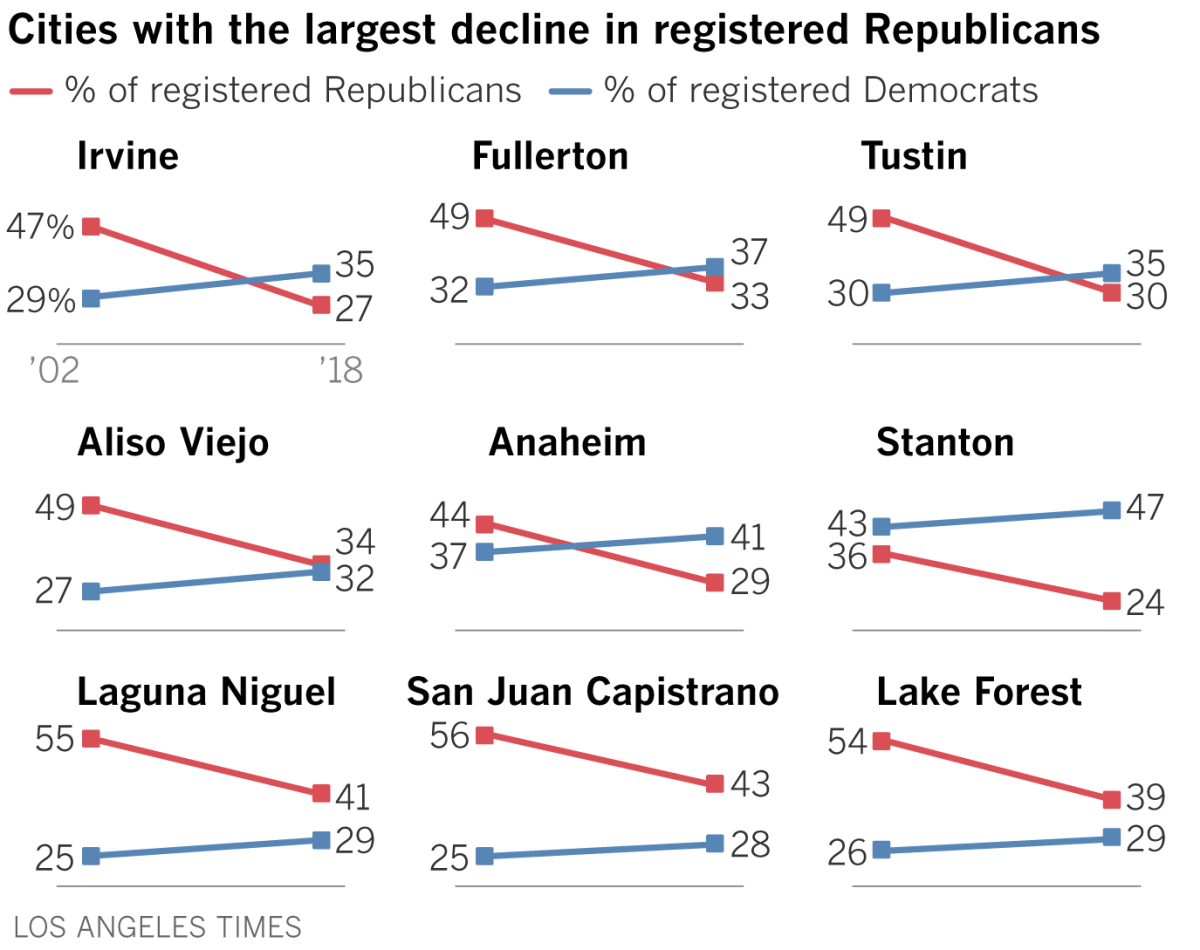

The Republican Party reached its peak in the Reagan era and has been slowly losing its membership edge since 1990, as the diversity of Los Angeles and the world at large started to bleed through the so-called Orange Curtain.

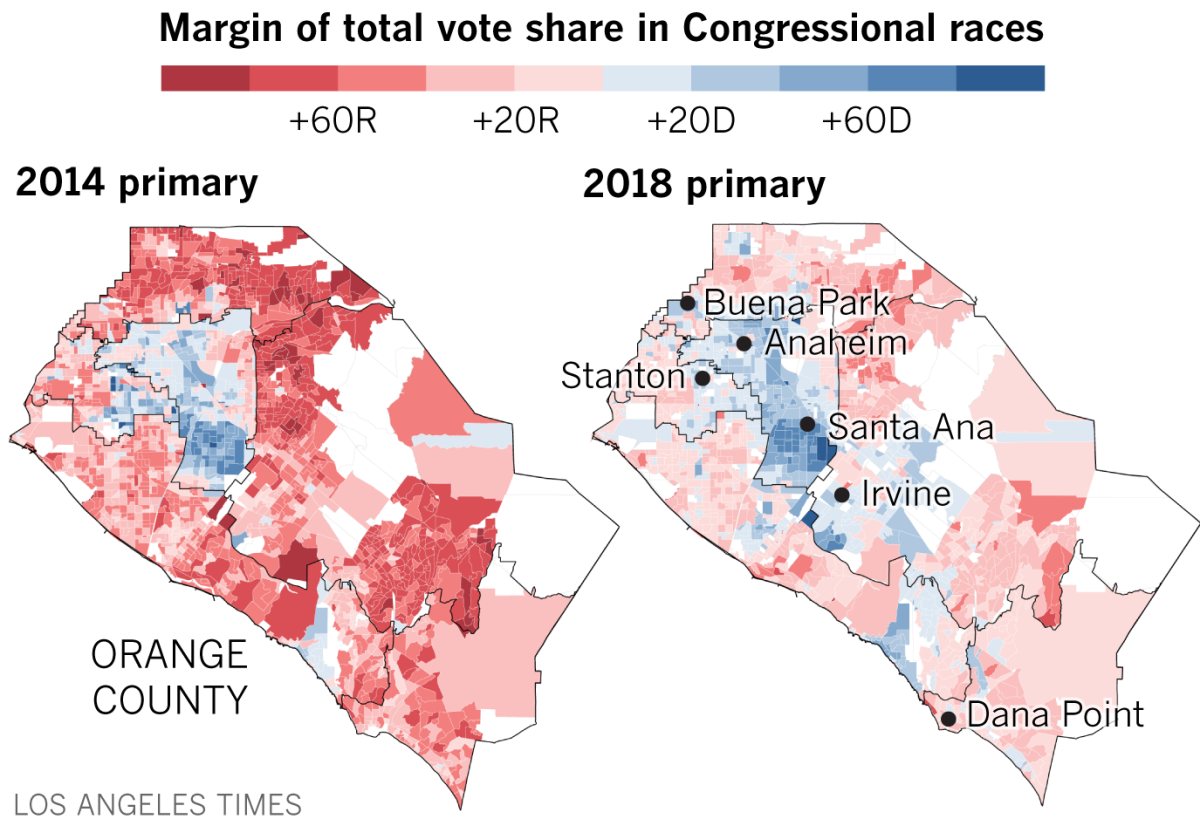

Registered Republicans today outnumber Democrats by only 2 percentage points, down from 22% at the peak, with a large contingent of self-declared independents positioned to swing elections either way. The GOP has a chance of losing four congressional seats in the county in Tuesday’s midterm election. If so, it would be the first time since the 1930s that Orange County would be without Republican representation in the House.

A GOP loss of even one or two seats would be significant, not as a turning point so much as a powerful sign of change — hastened by dislike for President Trump — in this one-time heart of American conservatism.

::

Orange County seceded from its northwestern neighbor, Los Angeles, in 1889, led by fiercely independent ranchers, sheepherders, beekeepers, citrus growers and crop farmers who had bristled under the control of a rich city 30 miles up the rail line.

The county then was a constellation of small farm and dairy towns in the north and scattered resort towns along the coast. In the south, the basin tapered off into a narrowing valley between the Santa Ana Mountains and the coastal San Joaquin Hills, where sheep and cattle ranches had thrived since California was part of Spain and Mexico.

Americans had taken over the ranchos in the late 19th century after a devastating drought left many old landowners of Spanish ancestry, the Californios, broke.

Lewis Moulton was one of the Yankee migrants. He came from Boston in 1874 and grazed sheep on the open range from Oceanside to Long Beach. Family lore has it that natural gas seeps were so rich in some spots that, as he camped, he would light them to cook his breakfast.

After two decades of renting land, he and a Basque shepherd, John Pierre Daguerre, had enough money to buy Rancho Niguel, which they eventually expanded to 22,000 acres. It was rugged, isolated country, good mostly for grazing. The cheapest land was the steep part near the coast, between what would become Laguna Beach and Dana Point — about $15 an acre. Today, small fractions of an acre go for double-digit millions.

In the second half of the 20th century, these backwater ranchers and farmers, the Moulton family, the O’Neills, Floods, Irvines, Segerstroms, would physically and culturally shape Orange County into the suburban giant it is today.

But there was always an underclass that made their dreams work.

Tenant farmers — often with roots in Mexico, the Basque country or in California before the American conquest — rented spots on these ranches to graze and grow barley. Others toiled as hands for the landowners.

In the north, they lived in segregated barrios in Santa Ana, Westminster, Anaheim and Garden Grove — where their children attended separate “Mexican schools” until a federal appeals court ruled them unconstitutional in 1947. In the south, they made up smaller communities in El Toro and San Juan Capistrano.

“My tata got killed right there by the train when he was 93 years old,” Stephen Rios said of his grandfather, an American Indian named Mochanai, as he sat in his front garden across from the Mission San Juan Capistrano. “He was a vaquero, a well-known horse trainer.”

Rios’ family worked for the Moultons and O’Neills and lived in the adobe house built in 1794 for their ancestor Feliciano Rios, who came to California as a Spanish soldier and married an American Indian woman.

Rios, an attorney, inherited the home from his father and lives there today. His son’s bedroom has the ceiling boards that the famed bandito Joaquin Murrieta, a family friend known as the Robin Hood of El Dorado, would lift to hide in the attic in the 1850s. A flat-screen TV sits below them now.

The American Indian, Californio and Mexican residents of their dirt street — the oldest neighborhood in California — were conservative. “They loved their families, their church,” he said. “They loved their pieces of land. They were strong, religious independent people.”

Republicans reigned during the rural era. The land barons did not want labor organizers anywhere near their field hands.

When orange pickers walked out of the orchards in 1936, the strikers were arrested and beaten by police and mobs. The Times reported “old vigilante days were revived in the orchards of Orange County yesterday as one man lay near death and scores nursed injuries.”

Changes in Orange County’s 948 square miles — physical, demographic and political — have always rolled from north to south. While the Rios family was still living in the cowboy era, World War II brought rapid transformation to the northern part of the county.

The military needed more West Coast bases to fight the Japanese, and the open space between Long Beach and San Diego was perfect. The government built bases in Seal Beach, Los Alamitos, Santa Ana and El Toro.

Defense contractors and other big manufacturers followed: Hughes Aircraft, Rockwell, Ford Aeronutronic, Boeing, American Electronics, Beckman Instruments.

The farmers and ranchers became developers, or sold their land to other builders, creating vast tracts of homes across the northern end of the county from Huntington Beach to Fullerton. In this era of big cars and backyard barbecues, houses turned inward. Garages replaced porches and picture windows; neighborhoods were quiet.

The newcomers, many from the South and Midwest or white-flighters from Los Angeles, converged at church.

::

At its core, Orange County held a tension between Midwestern traditionalism and California’s drive for reinvention.

The midcentury suburbs in the north were libertarian-leaning enclaves, yet living on Washington defense spending, and listening to a sunny California-bred gospel of self-empowerment and prosperity.

An Iowan named Robert Schuller put out a newspaper ad in 1955, “Come as you are … In the family car!”

He preached from the roof of the snack bar at the Orange Drive-in theater, not about fire and brimstone, but about “possibility thinking” with catchphrases like “Turn your scars into stars.”

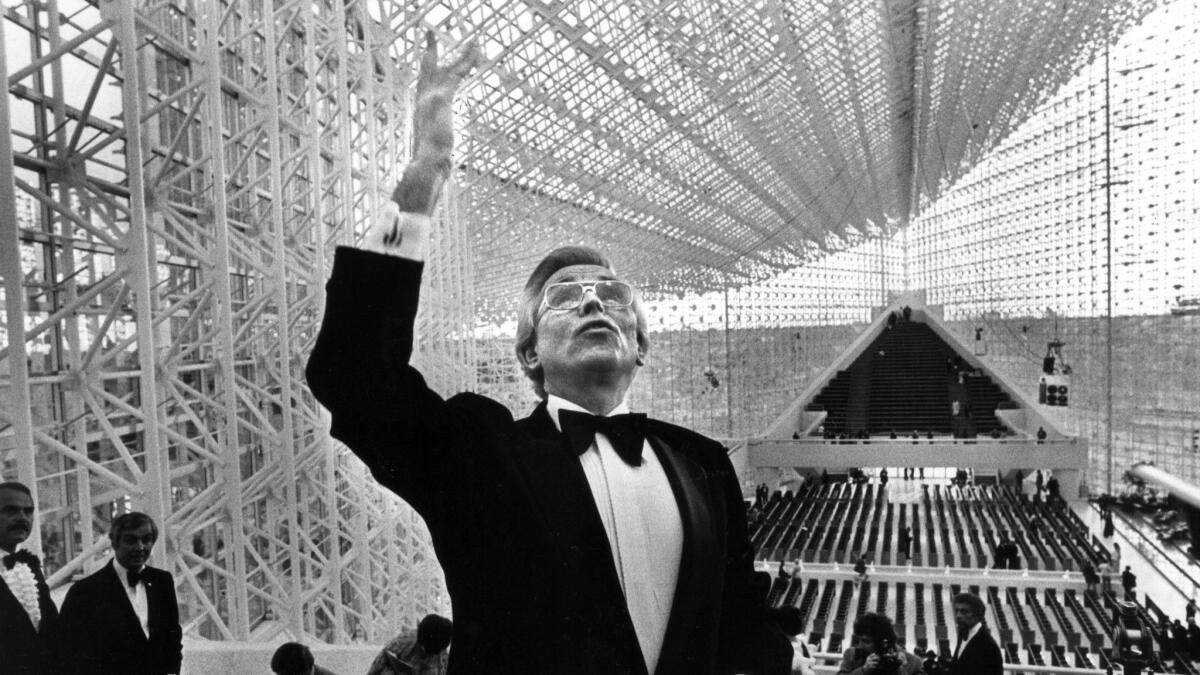

Schuller’s congregation boomed, becoming one of the nation’s first megachurches. His “Hour of Power” television sermon beamed across the country. In 1980, he built a glass church longer than a football field, the Crystal Cathedral.

Orange County birthed hugely influential ministries that mixed God with conservative politics: Chuck Smith’s Calvary Chapel, Greg Laurie’s Harvest Crusade, Paul and Jan Crouch’s Trinity Broadcasting Network and Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church.

“The megachurches reinforced and marinated the conservatism coming out of the defense plants,” said Fred Smoller, associate professor of political science at Chapman University.

Orange County’s open space and space-age technology, coupled with fervent entrepreneurship and an-edge-of-the-continent mentality, let tinkerers and visionaries experiment with minimal regulation.

This was a suburban county that, like no other, reached deep into popular culture.

Knott’s Berry Farm was the nation’s first theme park. Disneyland became one of the world’s biggest destinations. The ministries reached millions. South Coast Plaza shopping mall would draw more people from around the world than Disneyland. The Irvine ranch grew into the largest planned city in America. Leisure World became the first retirement community.

In new coastal towns such as Dana Point and San Clemente, Hobie Alter, Gordon “Grubby” Clark and John Severson (living next door to Orange County native Richard Nixon in his “Western White House”) helped create a whole new culture around an ancient Polynesian sport that would become a multibillion-dollar surf industry.

In Laguna Beach, Tom Morey, a Douglas Aircraft composites engineer, invented the bodyboard. In Anaheim, the Van Doren brothers opened the first Vans store.

And the likes of Knott and Anaheim’s Carl Karcher, the founder of Carl’s Jr., would help give America a new brand of conservatism, with their friend John Wayne in Newport Beach to embody it.

With the Cold War at its peak in the 1960s, families in Orange County, so many of them in the military or defense industry, heeded their call.

“At living room bridge clubs, at backyard barbecues, and at kitchen coffee klatches, the middle-class men and women of Orange County ‘awakened’ to what they perceived as the threats of communism and liberalism,” wrote Lisa McGirr, a professor of history at Harvard, in “Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right.” “They became the cutting edge of the conservative movement in the 1960s.”

“The lack of a large organized working class and the near absence of racial minorities made it likely that Orange County’s political rainbow would consist of relatively few colors.”

The quiet homogeneity of the walled and gated communities allowed politicians to exploit fears of the outsider — whether they be African Americans from Los Angeles, immigrants from Mexico, or gays, Muslims and Koreans.

“The anti-minority stuff accelerated political careers here,” said Smoller, the political scientist. “We have a history of sending some real oddballs to Congress.”

An early one was Rep. James Utt, who in 1963 warned about the United Nations training “a large contingent of barefooted Africans” in Georgia to take over the country.

Cementing this conservatism: its daily newspaper, the Register, and its libertarian owner Raymond C. Hoiles. He had once waged war against a measure to improve mental health care in Alaska because he said it was a communist plot to brainwash Americans in concentration camps.

Will California flip the House? The key races to watch »

In 1964, Pat Donnelly, a young aerospace engineer working at McDonnell Douglas, bought a small home in Buena Park for $18,500. His neighbor’s first admonition to him: They must help ensure no blacks, Mexicans or Catholics moved in.

Donnelly was a Catholic, and even worse, a union-card-carrying Democrat who once played guitar and banjo in a touring folk band. He and his wife had two girls and joined the St. Pius V Church on Orangethorpe Avenue and started a choir. With his own slice of suburbia, he became more concerned about taxes and grew more conservative.

“I didn’t like some of the stuff I was seeing in the cities, the drugs and crime. It seemed like people were abusing welfare. I was paying for that.”

He switched parties and never looked back.

After Orange County’s favorite candidate Barry Goldwater lost to President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, Republican rainmakers turned their attention to Reagan’s run for governor. His first political fundraiser was at a home in Anaheim, and the county would nurture his ambitions the rest of his career.

By the 1970s, developers had reached deep into south Orange County. The Irvine Co. had wound down its cattle operations and was parceling out its 185 square miles of land. Some 1,500 acres near Newport Beach would become UC Irvine. The company developed a master plan for a city to grow around the university, which would incorporate in 1971.

The Moultons sold their land soon after to developers who would build Laguna Hills, Laguna Woods, Laguna Niguel and Aliso Viejo. In their yards, homeowners would find rattlesnakes that wandered out of the wild canyons and steep hillsides between subdivisions.

To the east and south, the O’Neills’ vast scrubby land would give way to even newer, posher cities such as Rancho Santa Margarita, Ladera Ranch and the community of Coto de Caza — the setting for the “Real Housewives of Orange County.”

With all this construction, Stephen Rios’ 225-year-old adobe home is hemmed in by suburbia.

The “Los Rios District” is now on the National Register of Historic Places and is highly sought-after real estate for its quaint atmosphere.

Most of the old Californio families sold and moved on.

“Everyone else wants to live here now,” Rios said.

Lewis Moulton’s great-grandson, Jared Mathis, came back from a job back east to Laguna Hills to manage the family’s remaining holdings. A few years ago, he took his dad — who moved away in the 1970s — for a drive to look at the old ranch where he grew up.

But his father couldn’t get his bearings. All the landmarks were gone, the hills terraced, new trees and houses blocked once wide views. “They say they moved more dirt building Aliso Viejo than they did digging the Panama Canal,” Mathis said.

Mathis drove his father to the ridgeline of Laguna Beach. From there, you could see the whole ranch area, smell the laurel sumac in Aliso Canyon, glimpse some old corrals in the distance, get a grip of the topography. The white striations of terraced neighborhoods faded in the haze. The twin peaks of Modjeska and Santiago, called Old Saddleback, framed the view, as they did in most of the county, one thing that never changed.

“He could see where they had the old roundups,” he said. “That was a powerful image for him.”

As development moved south, the older, northern parts of the county lost some of their luster. The affluent white Republicans drifted to the shinier places depicted in shows such as “The O.C.”

The explosion in South County home construction created thousands of jobs. “The people building all of those houses were Latino,” said Smoller, the political science professor. Like the old tenant farmers, they helped families such as the Irvines realize their dreams.

Thousands of other Latinos would follow to work in service jobs in these wealthy new areas.

The humming economy overall and good schools also lured professional and middle-class Latinos to the northern neighborhoods that Anglos were leaving in their migration south.

In Santa Ana in the 1970s, the population of Latinos went from 40,000 to 90,000. Today, Latinos account for 78% of Santa Ana’s population. Northwest Orange County looks a lot like Southeast L.A. County. La Habra is 57% Latino; Anaheim, 52%; Buena Park, 40%; Garden Grove, 37%.

The other big factor that brought demographic change was seeded 53 years ago, when the federal government removed racist quotas on immigrants from Asia, and Greater Los Angeles became a major destination for Koreans and Chinese.

In 1975, after Saigon fell, 50,000 South Vietnamese landed in nearby Camp Pendleton, and conservative Orange County stepped up to take the anti-communist refugees.

The Register called on churches and citizens to sponsor these newcomers. They were put up in apartments in neglected parts of Westminster and Garden Grove still surrounded by bean fields.

Soon the fields and dilapidated commercial strips gave way to bustling places such as Saigon Market and Hoa Binh Market, ushering in a wave of new Vietnamese businesses that would revitalize the area.

Frank Jao started off in America selling Kirby vacuum cleaners in Whittier. Within a year, he moved to Garden Grove, became a real estate agent, then developer, first building a shopping mall in Westminster with the help of Chinese investors.

So many Vietnamese storefronts were opening in Westminster, changing its look so rapidly, that more than 100 residents signed a petition calling for the city to stop issuing business licenses. It was an ugly time.

“Anyone driving on Bolsa would more than occasionally be confronted by drivers who rolled down their windows and asked us to roll down ours, and they’d give us the middle finger,” recalled Jao, now 70. “When we’d go to work in the morning, we’d find the windows shot out by BB guns.”

His buildings became the core of Little Saigon, notably its landmark Asian Garden Mall. His company built $400 million worth of shopping centers and apartment buildings throughout Orange County and beyond.

Upscale Chinese families took to Irvine. Many had left China because of the lack of opportunities for their children to attend college, and this master-planned community, built around UC Irvine, was a huge draw, as it was to moderately affluent Koreans, Iranians and Latinos. Irvine is nearly 40% Asian now.

Koreans had begun trickling in from Los Angeles during the 1980s, seeking better schools. The 1992 Los Angeles riots, in which many Korean store owners lost their businesses, sped up the flow. They often stuck close together, moving into specific neighborhoods in Garden Grove, Fullerton and Buena Park.

The Asian influx has also contributed to the reordering of politics in once reliably Republican Orange County.

As a whole, Asian Americans are more likely to register as “no party preference” and vote based on specific issues, not party, said Karthick Ramakrishnan, a professor of political science and public policy at UC Riverside. They leaned Republican during the Reagan era and well into the 1990s while subsequent generations moved to the left.

“About one-third of Asian Americans voted for Clinton in 1992,” Ramakrishnan said, “but two-thirds voted for Obama in 2008.”

He said in the last five years strong GOP outreach to the community in Orange County — and encouragement of Asian Americans to run for office — has brought many back to the party. But Ramakrishnan said too many factors are at play to say how they will vote on Tuesday. An example: They don’t like Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric, but Vietnamese, Taiwanese and Koreans like his confrontational stance toward China.

In Buena Park, Pat Donnelly, still a Republican, met a Korean American estate attorney named Sunny Park — a Democrat — at his Lion’s Club. He came to realize she had values he admired: honesty, a family focus, strong work ethic. Now he’s campaigning for her as she runs for City Council.

Park had followed her aging Korean clients from Los Angeles, moving into the affluent and increasingly Korean Bellehurst neighborhood. When she knocks on doors, many white people have offered support. But some have grumbled “No Koreans” and shut the door in her face.

A couple weeks ago, she started seeing campaign signs that said “No Sunny Park, Carpetbagger.”

She says the message that sends the Korean community is that she — and by extension they — are not from here and they shouldn’t try to take part in politics.

The political dynamic in Orange County is not so much a rising blue tide, but an ebbing red one. Since 1999, registered Democrats rose by less than 2 percentage points to 33.6%, while Republicans have fallen 14 points to 35.6% of voters. The wave is of independent voters who increased in numbers nearly as much as the Republicans fell.

A majority of Latinos vote Democrat, and growth in their community has buoyed the party. While they tend to be more socially conservative, they favor more lenient immigration policies, social programs that help the poor, strong unions and high minimum wages.

Historically, turnout has not matched their share of the population, but some Republican strategists fear Trump’s derogatory comments about Mexican and Central American immigrants might motivate them this year.

In 1996, the anti-immigrant rhetoric surrounding Proposition 187 helped end the ultra-right Orange County Republican Bob Dornan’s political career, and put Democrat Loretta Sanchez in Congress.

Just like the development, the diversity and Democratic edge are pushing south in this county of 3.2 million people.

In 2002, Democrats outnumbered Republicans only in Santa Ana, Buena Park and Stanton. Now they do in 11 cities reaching down to Irvine.

In Laguna Niguel, Candy Antone, 47, said Democrats such as her essentially lived in the closet until recently. She would go quiet when a Republican friend or neighbor would go on a political rant. “You just had to bite your lip,” she said.

But Trump is repelling even many Republicans here. “Democrats are coming out of the woodwork,” Antone said. “People we’ve known for years, we’re just finding out they’re Democrats.”

Twitter: @joemozingo

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.