Trump says June 12 nuclear summit with North Korea is back on

Reporting from Washington — President Trump on Friday declared that his on-and-off summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in Singapore is on again, even as he tried to move away from his previous suggestions that a quick deal could be hatched during the unprecedented meeting less than two weeks from now.

“We’ll see where it leads, but we’re going to meet June 12,” Trump said after meeting for more than an hour with one of Kim’s top deputies in the Oval Office.

“I think it’ll be a process,” Trump continued. “I never said it goes in one meeting. I said it’d be a process.”

In fact, Trump, in comments as recently as a month ago, had suggested that a single summit meeting could lead to a dramatic breakthrough, talking about staging a “great celebration” of an agreement to eradicate North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. Most outside analysts, as well as government experts, believed those comments set unrealistic goals.

In addition to lowering expectations for the meeting, Trump deemphasized the U.S. connection to Asia in a way that reversed language used by his predecessors for decades and was sure to rattle U.S. allies.

“We’re 6,000 miles away,” Trump said. “That’s their neighborhood; it’s not our neighborhood,” he said, declaring that Japan and South Korea, not the U.S., would have to bear the major cost of any reconstruction of North Korea’s economy.

Last week, Trump had announced he was canceling the summit because of “hostile” North Korean statements. Friday’s tableau, unimaginable just a few months ago, set a very different tone.

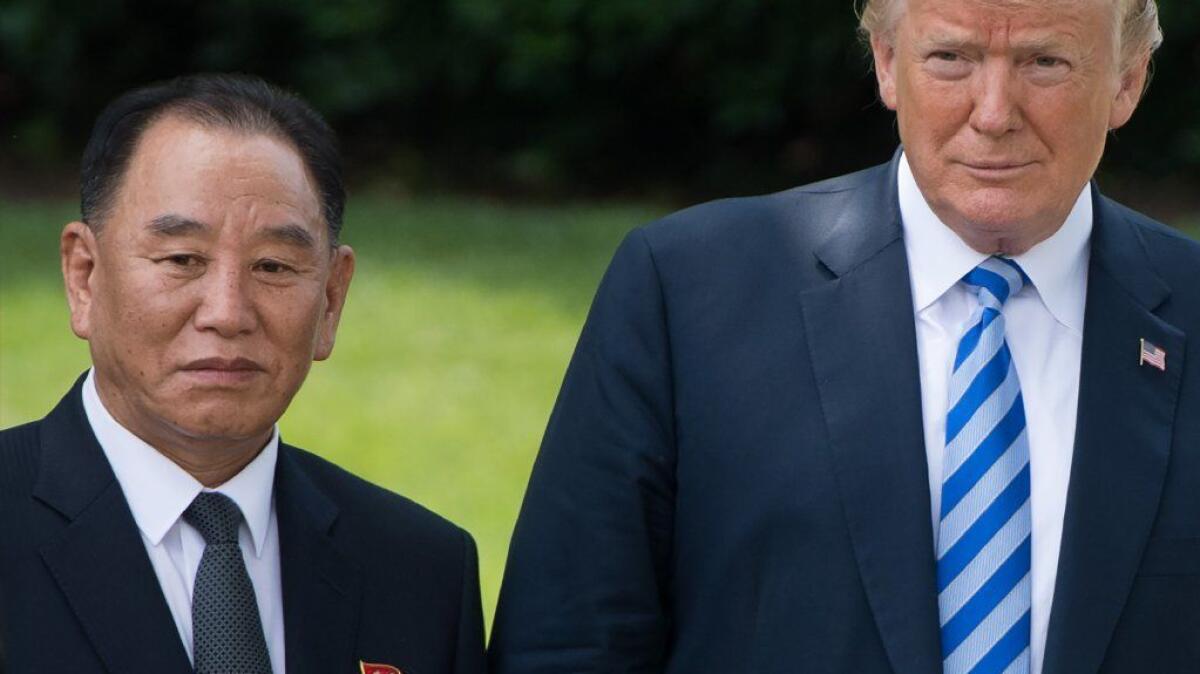

The North Korean official, Gen. Kim Yong Chol, a former spy chief who is one of his country’s most powerful figures, was greeted by Chief of Staff John F. Kelly at the White House’s south driveway upon his arrival. He was the highest-ranking North Korean to visit the White House in nearly two decades.

The general, accompanied only by an interpreter, met with Trump, Kelly and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in the Oval Office, where he presented a letter from Kim Jong Un to Trump. Notably absent was Trump’s national security advisor, John Bolton, whose comments last month suggesting that North Korea follow the model of Libya in abandoning its nuclear program had threatened to derail the summit.

Afterward, Gen. Kim and a larger entourage were escorted to the White House driveway, where Trump engineered a photo-op, turning everyone to stand side by side and face the television cameras.

The delegation from a country dubbed by Trump’s last Republican predecessor as a member of the “axis of evil” shook hands, smiled and posed for pictures with their host after talks that Trump branded a “getting-to-know you meeting — plus.”

Trump teased at the contents of Kim’s letter, calling it “very nice” and hinting that he might release it publicly, only to insist minutes later that he had yet to read it.

“This was a letter presentation,” he said after the North Koreans loaded into their cars. “It ended up being a two-hour conversation … I really think they want to do something, and if it’s possible, so do we.”

“They want it, we think its important, and I think we’d be making a big mistake if we didn’t have it,” Trump said at another point, referring to the summit meeting.

Trump made a point of saying that he and Kim Yong Chol discussed sanctions relief as well as denuclearization. The U.S. would hold off on “hundreds” of new sanctions against North Korea that had been planned, Trump said, although existing sanctions would remain in force.

He also said he had not raised North Korea’s record of brutal human rights violations — a subject that administration officials highlighted repeatedly until just weeks ago.

Trump seemed eager to build bridges with North Korea, talking of ending sanctions against the isolated adversary.

“I don’t even want to use the term ‘maximum pressure’ anymore,” he said, referring to the phrase the administration has used for months to describe its policy toward Pyongyang. “We’re getting along.”

Trump’s repeated insistence Friday that the summit meeting would only be an initial step, rather than a place to cut a deal, built on language he started using in the past week.

In traditional summits, heads of state meet only at the end of negotiations, after lower-level officials have hammered out details for an agreement. That has not happened this time, as Trump has been eager to press the flesh with Kim Jong Un since March, when South Korean officials reported to him that the North Koreans had proferred an invitation.

That tempering of his own enthusiasm marks a notable shift for the president.

Just over a month ago, Trump floated the possibility of holding the summit meeting in the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea, suggesting that would be the most fitting spot for the triumph he was hoping for, if not outright expecting.

“There’s something I like about it, because you’re there, if things work out, there’s a great celebration to be had on the site, not in a third-party country,” he said then.

“The United States has never been closer to potentially having something happen with respect to the Korean Peninsula, that can get rid of the nuclear weapons, can create so many good things, so many positive things, and peace and safety for the world,” he added then.

But his advisors have cautioned him that a deal to curb or eliminate North Korea’s nuclear stockpile could take months — if not more — to reach, and then years or decades to carry out.

The latest attempt to revive the summit began with talks in New York on Thursday between Pompeo and Kim Yong Chol.

The four-star general is under multiple U.S. sanctions, and he needed a State Department waiver to enter the country.

That diplomatic gesture, and the welcome he received in the Oval Office, were a sign of the White House’s eagerness for a breakthrough with the isolated nuclear-armed regime.

Just months ago, Trump and Kim Jong Un were trading crude insults — “Little Rocket Man” versus “mentally deranged U.S. dotard,” among others — and threatening to launch nuclear war with what Trump called “fire and fury like the world has never seen.”

And just eight days ago, Trump wrote a terse letter to Kim Jong Un calling off the summit but leaving a window open for further talks.

Since then, the two governments have engaged in intense bouts of diplomacy in New York, Singapore and in the DMZ to see if the summit should go forward. Teams have scrambled to arrange security, logistics and an agenda for the two leaders.

Trump has been eager to put himself in the middle of the negotiations on a possible deal to restrict North Korea’s nuclear weapons program; and he believes his own tough talk toward Kim has been a major factor in bringing the North Koreans to the table. On Thursday, when he first disclosed the North Korean delegation’s desire to bring him a letter, he said talks have gone “very well” and are “in good hands.”

Friday’s visit by Kim Yong Chol is similar to a visit to Washington in 2000 by Vice Marshal Jo Myong-rok, then North Korea’s second-most powerful official. Jo met with President Clinton and delivered a letter from Kim Jong Il, North Korea’s leader at the time and the father of the current leader.

That meeting, which occurred during an another era of optimism, included an invitation for Clinton to visit Pyongyang to seal a deal to restrict the country’s ballistic missile program. Neither the visit nor the missile deal came to fruition, and North Korea has since steadily expanded its missile and nuclear programs.

Robert L. Gallucci, who led the 1994 nuclear negotiations with North Korea for the Clinton administration, said Trump’s opening gambit — unconditional surrender of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal — was a nonstarter.

“That they do everything and we do nothing ... sets an expectation that can’t be met,” Gallucci said.

“There will have to be concessions” by the U.S., he said, possibly including a “manifestation of normalcy” that goes beyond a peace treaty to replace the armistice that halted the Korean War in 1953.

Other concessions might involve changing or downgrading the annual joint U.S.-South Korea military exercises. Contrary to conventional wisdom, however, Gallucci said, the North Koreans, as far back as 1994, have not insisted on the withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Korea. That demand, instead, is far more important to China, which sees the American troops as a U.S. beachhead in the Asia-Pacific region, Gallucci said.

Jonathan Pollack, an Asia expert at the Brookings Institution, said the hurry to hold a summit could have negative consequences.

“One troubling possibility, in the rush to get across the finish line, is a bad agreement ... that Trump talks up,” Pollack said. “I’m almost imagining a scenario looking ahead a couple of weeks: The television media saying this is the moon and the stars, [but] you wake up the next morning and look at the fine print and see it is not there.”

Staff writer Tracy Wilkinson contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

3 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details on the White House meeting and analysis.

11:50 a.m.: This article was updated with the announcement of the revived summit.

11:05 a.m.: This article was updated with the meeting getting underway.

This story was originally published at 9:15 a.m.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.