Gavin Newsom faces backlash as state fights Sierra Club and San Francisco over waterfront

- Share via

One of Gavin Newsom’s few duties as lieutenant governor is to serve on the State Lands Commission, a powerful agency that governs much of California’s shoreline.

The three-member panel rarely draws public attention. But now its lawsuit to overturn a San Francisco ballot measure that can limit the height of waterfront developments is stirring up trouble for Newsom as he runs for governor.

If the Lands Commission wins, environmental groups say, it could block voters statewide from passing local ballot measures to restrict coastal development and oil drilling, as Santa Barbara, Santa Monica, Hermosa Beach and other communities have done for decades.

Promoted by the Sierra Club, Proposition B, passed by 59% of San Francisco voters in 2014, requires voter approval for any waterfront project that exceeds the city’s height limit. But the Lands Commission, chaired by former San Francisco Mayor Newsom, says state law prohibits voters from having a direct say on the use of public waterfront.

“I think it’s a stab in the back of the city he once governed,” said Becky Evans, a leader of the Sierra Club’s San Francisco Bay chapter.

Newsom declined to be interviewed. Instead, he released a statement saying the agency had stopped “harmful industrial proposals up and down the state.”

“I believe that the Commission strikes the right balance, where we support and protect local communities from bad projects while upholding the environmental interests of all Californians, and that’s what I intend to push for as we settle this matter,” he said.

A trial is scheduled to start Sept. 11, but Superior Court Judge Suzanne Bolanos might call it off and issue a final judgment as soon as June 28.

For Newsom, whose record usually wins praise from environmentalists, the court battle against the Sierra Club is awkward. And at a time when he’s arguing in the campaign that economic inequality is California’s No. 1 problem, the commission that he leads is faulting San Francisco’s Proposition B for bringing more affordable housing to its high-priced waterfront.

The lawsuit has also opened Newsom to accusations that he disrespects one of California’s most cherished political customs: initiative and referendum.

“He’s suing his own city to take away the right of the citizens to vote on development of their public land on the waterfront,” said Art Agnos, San Francisco’s mayor from 1988 to 1992. “This is Mr. Citizenville, the man who says we’ve got to do government from the bottom up, except when it runs into his fat-cat contributors in the development world.”

In his 2013 book “Citizenville,” Newsom called for using technology to put “power in the hands of the people.”

State Treasurer John Chiang, one of Newsom’s rivals in the 2018 governor’s race, was chairman of the Lands Commission when it filed the suit in July 2014. Chiang, who lives in Torrance, is no longer on the commission and doesn’t share Newsom’s long history of siding with developers in San Francisco’s perennial battles over the city’s prime real estate.

The state entrusted more than seven miles of San Francisco waterfront to the city under the 1968 Burton Act, sponsored by John Burton, then an assemblyman.

Burton, now state Democratic chairman, accused the commission of trying to clear the way for developers to build luxury high-rises on the scenic waterfront in violation of the public trust. Pausing briefly from an outburst of cussing, he said: “I disagree with the lieutenant governor, and he knows that.”

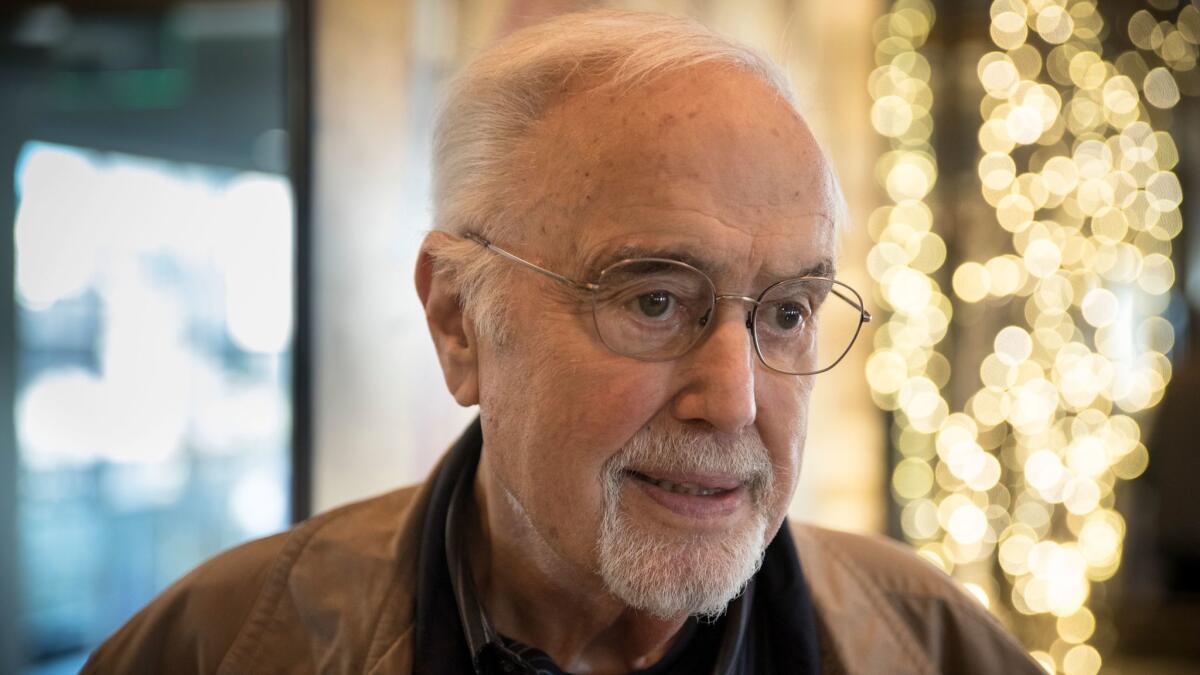

Newsom, a Democrat, was mayor from 2004 until 2011, when he took office as lieutenant governor. He has moved to Marin County but remains active in San Francisco politics.

In 2013, he urged San Francisco voters to pass twin ballot measures pushed by a developer who needed a waiver of city height limits to build an upscale 12-story condo project on the Embarcadero, just north of the landmark Ferry Building.

The builder, Pacific Waterfront Developers LLC, spent more than $2 million on the campaign, much of it for television and mail advertising that featured Newsom. In one mailing, Newsom told voters the project offered “new waterfront open space for everyone to enjoy.”

Campaigning to kill the project were the Sierra Club, neighborhood groups and Agnos, among others. They reminded voters of the ugly double-deck Embarcadero Freeway that was demolished after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. A “giant new wall” of condos would block public views of the bay, they warned.

Voters defeated both measures by wide margins, effectively killing the project. Encouraged by the result, the Sierra Club coalition put Proposition B on the June 2014 ballot and easily won that campaign too.

For Newsom, pro-development donors on all three ballot measures — mainly builders, real estate brokers and construction unions — have been a big source of donations, giving more than $160,000 to his campaigns for governor and lieutenant governor, records show.

A few weeks after the Lands Commission filed suit, a clutch of Sierra Club protesters gathered outside a meeting of the panel at the Ferry Building. Their signs demanded that Newsom drop the case.

Inside, Jon Golinger, director of the Yes on B campaign, told Newsom and his colleagues that San Francisco had voted on 18 waterfront ballot measures in 45 years, including approval of the Giants’ ballpark and restoration of the Ferry Building.

“Is it your position that the building we’re in was renovated illegally, and that all those ballot measures should be rescinded, and voters should never have a say again?” he asked.

Newsom declined to respond. “It wouldn’t be constructive,” he told the audience.

Since Proposition B’s passage, San Francisco voters have approved two big waterfront developments, each a mix of housing, retail, office and recreation: Pier 70 and Mission Rock, near a Warriors basketball arena now under construction.

The Lands Commission says that fear of voter rejection led builders of both projects to add more affordable housing and lower building heights.

Reduced height “can diminish revenue because the highest floors generally have the best views and command the highest rents,” Deputy Atty. Gen. Joel S. Jacobs argued for the Lands Commission in court papers.

Lower-value projects, he said, yield less tax money for waterfront improvements like pier repairs. That was part of the commission’s broader case that San Francisco’s voter-approval measure unlawfully puts local concerns ahead of the statewide public benefits that the city is entrusted to protect.

“Proposition B made the decision-making process less focused on the public trust, and more focused on the whims and parochial desires of San Francisco voters,” Jacobs said.

When voters weigh in on a project, he argued, it’s impossible to know whether they’re subjugating statewide public benefits to local concerns. By contrast, he said, local government officials can produce a written record showing that statewide public interests were paramount in their evaluation of a project’s merits.

Louise Renne, a lawyer for Burton and the Sierra Club, called the state’s argument “a perversion of the public trust.”

“I don’t think the rest of the state realizes the full implications of the position that the State Lands Commission has taken,” she said. “If the State Lands Commission wins, it means that local governments literally are going to have little or no say in their waterfronts and coastlines.”

City Atty. Dennis Herrera, who is defending San Francisco, said the result of giving voters a say on the waterfront speaks for itself. “We have an urban waterfront that is the envy of cities worldwide,” he said.

The Lands Commission oversees public use of most California waters up to three miles from the tide line, including highly valuable landfill in places like San Francisco Bay and Long Beach harbor. The state Coastal Commission has overlapping jurisdiction, but controls development on a much wider expanse of land, in some places stretching several miles inland.

Newsom’s main duties as lieutenant governor are to serve on the Lands Commission and the UC and California State University boards. He has skipped 25 of the 50 Lands Commission meetings on his watch, sending aides to attend on his behalf, as other commissioners also frequently do.

Rhys Williams, a spokesman for the lieutenant governor, dismissed the criticism of Newsom as hyperbole “rooted purely in San Francisco political tribalism.” He suggested that those attacking him turn their attention to Chiang.

Williams highlighted Chiang’s frequent absences when, as state controller, he served on the Lands Commission but did not mention the attendance lapses of state Finance Director Michael Cohen, the panel’s third member when the suit was filed.

Chiang, who left the commission after he was elected treasurer in 2014, said its job was to protect public land “from over-development, environmental harm and constricted public access.”

“While discharging that duty on behalf of 39 million Californians most often left industrialists, real estate developers and Big Oil angry and dejected, it also meant occasionally asking local governments to place the greater public good over narrow provincial interests — some wanting more development, others less,” he said.

A Cohen spokesman declined to comment, as did Jennifer Lucchesi, the executive officer of the Lands Commission.

Times Staff Writer Ben Welsh contributed data analysis to this report. Newsom’s campaign contributions were drawn from the California Civic Data Coalition’s archive of data collected by California’s Secretary of State. Learn more about the candidates and their fundraising.

ALSO

De León sends candidate-style political video — but says he has no imminent political plans

Trump presidency eases Gavin Newsom’s path in his second run for California governor

Vulnerable House Republicans fear political consequences after healthcare vote

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.